Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Frame of Reference

Generational Theory

The origins of generational theory lie within the field of sociology, where sociologist Karl Mannheim (1893-1947) started to emphasize the importance of generations to gain a better awareness of social and intellectual movements. According to Manheim, generations consist of two important elements. First, members of the same generation have to share the same range of birth years, in other words they share common location in historical time. Furthermore they have to be capable of participating in certain collective historical experiences that will create a concrete bond between each member, to share a mutual identity of responses (Mannheim, 1952). The second element of historical experiences has been studied and further refined by Turner (Edmunds & Turner, 2002; Eyerman & Turner, 1998; Turner, 1998) who’s results revealed cultural elements such as music or technological advances were found to influence and help shape generations. Every new generation forms their own unique reactions according to social forces like laws, schools and families (Baltes, Reese & Lipsitt, 1980). Individuals do not have the option to be part of a generation, nor are members necessarily aware of their membership (Kowske, Rasch & Wiley, 2010). Instead membership in a generation is based on a shared position of an age group (Mannheim, 1952).

Egri and Ralston (2004) explored the impact that significant cultural, political and economical developments facing different generations in their pre-adult years had on their value orientations, and how they varied accordingly. They discovered for instance that generations experiencing war may grow up with modernist survival values such as materialism and respect for authority. In contrast, generations growing up within a socioeconomically secure background may value postmodern qualities such as egalitarianism and tolerance of diversity.

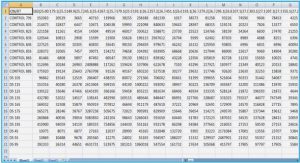

In order to allocate each generation to their years of birth, we refer to Table 2-1, from one of the most frequently cited books on generational theory, Strauss and Howe (1991).

Although it is possible to have all four generations present in the modern workforce, recent studies have found a significantly low number of veterans remaining in the workforce to obtain a proper sample for analysis. As such, this generation will not be addressed in detail or further analyzed in this study.

Baby Boomers

Growing up during Cold war, Baby boomers expect the best from life (Kupperschmidt, 2000). Attitudes such as intellectually arrogant, culturally wise, critical thinkers and self-confident portray Baby boomers as much heralded, but failing to meet expectations (Strauss & Howe, 1991; Howe & Strauss, 2000). According to Smith and Clurman (1997) they want to be on top and in charge and have a foible for status symbols (Adams, 1998).

Generation X (Gen X)

Gen X grew up with financial and societal insecurity that led to a preference of individualism over collectivism (Jurkiewicz & Brown, 1998). Strauss and Howe (1991) and Howe and Strauss (2000) describe them as cynical, distrusting, independent and self-reliant. They highly value the development of skills to move into management (Eisner, 2005) and prefer a coaching style of management with plenty of recognition for results (Zemke, Raines & Filipczak, 2000).

Generation Y (Gen Y)

Gen Y, currently entering the job market, is socialized in a digital world and constantly connected to digitally streamed information and contacts (Eisner, 2005). They desire minimal rules and bureaucracy (Morrison, Erickson and Dychtwald, 2006), demand flexibility to move from project to project (Martin, 2005) and prefer openness and transparency (Eisner, 2005) combined with a high expectation of empowerment (Shaw & Fairhurst, 2008). Strauss and Howe (1991) and Howe and Strauss (2000) describe Gen Y with attributes such as team players, smart and optimistic

Work Values

Values define what an individual, or group of individuals believe to be fundamentally right, or wrong (Smola & Sutton, 2002). This holds true in many contexts, whether it be social values, religious values or family values. Therefore, this simple description can be applied to an individual’s work values, as what one feels as right or wrong within the work setting (Smola & Sutton, 2002). However the consensus was that a more comprehensive definition was required and thus the definition used in this study, among others was proposed by (Dose, 1997) stating that work values are the evaluative standards relating to work or the work environment by which individuals discern what is ‘right’ or assess the importance of preferences (Dose, 1997; Parry & Urwin, 2011; Smola & Sutton, 2002).

When studying values of individuals from multiple generations or age cohorts, the question is naturally raised regarding whether values can be attributed to the generation within which one resides, of if values change over time as a function of age or life stage. This issue was addressed by Rokeach (1973) (as cited in Cogin, 2012), who argued that individuals develop values in their early years, and these values remain fairly constant over the course of their lives. The extent to which an individual attributes importance to certain values may change over time, however the appreciation for the value does not. This idea was supported up by Lyons, Duxbury and Higgins (2007) who suggest that “values are enduring but not immutable. They are learned during an individual’s formative years and remain fairly constant over the life course” (p. 340)

Generational Work Value Differences

The increasing value of leisure is often considered as the largest change in work values. Quantitative research done by Twenge, Campbell, Hoffman and Lance (2010) discovered a generational shift in the value of having free time between both, Gen Y relative to Gen X as well as Gen X relative to Baby boomers. This refers back to the observation of Gen X and Gen Y grew up witnessing increased working hours while receiving limited vacation time. The same study also discovers a change in value of extrinsic rewards such as salary, which is appreciated more by Gen Y than Baby boomers. Demanding more money while working less shows a stereotypical sense of entitlement and overconfidence within Gen Y (Tulgan, 2009; Twenge & Campbell, 2008). Gursoy et al. (2013) found significant differences between ‘recognition’ comparing the three generations, finding specifically that Gen Y is more likely to perceive a lack of recognition and respect from their colleagues, more than Baby boomers and Gen X. However, Appelbaum, Serena and Shapiro (2005) found that baby boomers do indeed doubt the commitment of younger generations. Likewise Parry and Urwin (2011) identified in their study the craving of younger generations of immediate recognition through title, pay, praise and promotion. However also finding that Gen Y does show a strong will to get things done by believing in collective action and teamwork.

Specific generational characteristics regarding intrinsic values have been uncovered by Arnett (2004) as well as Lancaster and Stillman (2003) who found a decline of ‘pride’ and the ‘meaning for work’ within younger generations. Gursoy et al. (2013) uncovered in their quantitative research significant differences of ‘work centrality’ between Baby boomers compared to both, Gen X and Gen Y. In other words Baby boomers value their job more important than the other two generations. Another study done by Smola and Sutton (2002) confirm these findings, adding that newer or younger workers were less inclined to feel their work should be an important part of their life; and would be more likely to stop working if they suddenly came into a large amount of money. Likewise, research of Cogin (2012) discovered a decline of work ethic among young people including reluctance to working hard. Cogin (2012) further uncovered in her study a big contrast between Gen Y and Baby boomers regarding the level of satisfaction obtained from working hard. Where older generations equate ‘working hard’ to personal and professional success, Gen Y’s definition of success comes rather by attaining a solid work-life balance and flexibility. Gursoy et al. (2013) investigated work-life balance further as a work value. Contrary to Baby boomers, both, Gen X as well as Gen Y strongly believe in a separation of work and personal life with Gen Y being least attached to work. For Gen Y, friends and families will always be prioritized before work. Within this study these values are referred to as the “moral importance of work”.

Parry and Urwin (2011) identify in their study the need for guidance, direction and leadership of Gen Y where the older two generations tend to be less reliant on strong, competent leadership. Another contrasting attribute has been detected regarding ‘thinking outside the box’ which is strongly related to Gen Y. This type mentality is likely to bother both Gen X as well as Baby boomers, who are traditionally stuck to their well-established approaches. With respect to Gen X, they have a high ambition towards power, desiring quick promotions (Smola Sutton, 2002). Additionally they appreciate working independently (Chen & Choi, 2008; Tulgan, 2000) and self-direction (Lyons, 2003) the most among the three generations.

Martin (2005) discovers less respect for rank in regards to Gen Y in his research of managerial challenges concerning different generations. Several other studies have confirmed this result with each finding increased questioning amongst the younger generation for hierarchy in the workplace (Helyer & Lee, 2012; Zemke et al., 2000). Gursoy, Maier and Chi (2008) explain this trait with a strong believe in collective action and hence the preference of centralized authority. On the other end of the spectrum, older generations, especially Baby boomers, do respect authority, however wish to be viewed as an equal (Eisner, 2005; Helyer & Lee, 2012).

Eisner (2005) found that team spirit is most strongly developed within Gen Y, who prefers a management style involving team orientation. Martin (2005) found Gen Y performing better when working in teams, however they still work well alone. Likewise, the results of Cogin (2012) show teamwork is significant within younger generations, as well as building cohesion through social activity. Tulgan (2004) identified in his study a desire amongst Gen X towards teamwork, finding teamwork beneficial to support their individual effort and establish strong relationships (Karp, Sirias and Arnold, 1999). Additionally Karpet et al. (1999) discovered less team orientation of Baby boomers compared to Gen X, however research is available that argues that Baby boomers also value team work (Benson and Brown, 2011), thus there is no clear tendency identified regarding Baby boomer’s overall willingness or ability to work in a team environment

Age, Career Stage and Life Stage as Factors

One of the main criticisms associated with generational research lies within the complex interrelation and thus disassociation of generation from other contributing factors that can affect someone’s work values, primarily chronological aging career stage and life stage (Parry and Urwin, 2001; Rhodes, 1983; Twenge, 2010; Wong et al., 2008). This challenge was identified by Erickson (1968) and Gould (1978) who noted that when conducting cross-sectional research, there is no absolute method to know whether a result is really due to the generational group, maturation, the particular career stage occurring concurrently, or even the developmental stage that the person is in.

Rhodes (1983) describes aging with two effects. First is psychological aging, which explains the systematic changing of someone’s personality, needs, behavior and expectations over time. Different roles such as child, student, worker etc. carry certain expectations for behavior and have influence on someone’s needs. The second is biological aging that comes along with anatomical and physiological changes (Rhodes, 1983).

Wong et al. (2008) conclude that some work value differences could be better explained with career stage as a main contributing factor. Career stage theories (e.g., Super, 1957, 1980) claim that people progress during their career through multiple stages. Each career stage represents its own work attitudes and behaviors (Mount, 1984), thus people in the same career stage strive to gratify their work-related needs similarly (Bedeian, Pizzolatto, Long & Griffeth, 1991). In the study of Morrow and McElroy (1987), age, organizational tenure, and positional tenure were identified as three major criteria affecting an individual’s career stage. The most common approach in past research is to categorize career stage into three periods (e.g., Allen & Meyer, 1993; Bedeian et al., 1991; Morrow & McElroy, 1987). The first stage, or trial stage, is where a worker needs to discover their capabilities as well as interests. In the second stabilization stage, career advancement and consistency in aspects of personal lives are of bigger concern. The last stage, referred to as the maintenance stage, is where someone looks to maintain current status at work and hold onto his or her position.

Rhodes (1983) and Polach (2007) further researched the effect that certain periods in life have on someone’s behavior or values, rather than just considering age or generation. They arrived at the same conclusion as (e.g. Appelbaum et al., 2005; Johnson & Lopes 2008) who argue that some generational differences are more a factor of different life stages. Levinson (1978) established a model of adult development that recognizes diverse periods or cycles that adults pass through. By going through adulthood, people face new challenges and implement different social roles. Levinson (1978) identified key life events that typically signal a transformation in life cycle. These key events are entry to occupation, marriage, as well as starting a family

Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies

A considerable limitation facing researchers’ studying generational differences is as Twenge (2010) states “to put it facetiously, the lack of a workable time machine” (p. 202). This statement refers to the predominate use of cross sectional studies which collect data from individuals representing different generations, however at only one point in time. As such, any differences could be attributed to age, career stage, as well as generation, being nearly impossible to distinguish between each (Twenge, 2010). Rhodes (1983) agreed with this analysis of cross sectional studies concluding that they are an insufficient method of examining generational and cohort effects as it is impossible to disentangle the data this produced for either generational, or age effects. Parry & Urwin (2011) cite a number of studies (Appelbaum et al., 2005; Jurkiewicz & Brown, 1998; Lyons et al., 2007; Wong et al., 2008) which all claim to investigate differences between generations. However given that each used cross sectional data in their analysis, Parry and Urwin (2011) reiterate that it is impossible to be confident that the findings were not due to age or career, or life stage effects.

The solution to the issues raised by the use of cross sectional data is for researcher to perform longitudinal or time lag studies (Rhodes, 1983; Twenge, 2010). In these studies age is held constant as individuals of the same age are examined at different points in time. Therefore, any differences noticed between the sample sets can be attributed to generation, or time and period (changes over time that affect all generations) effects only. As such these time lag studies present distinct advantages over cross sectional studies when attempting to isolate generational differences (Twenge, 2010). The problem with conducting such studies is that in order to be reliable, they require sample sets of very similar demographics to be asked the same questions at different times and they can literally take generations to complete. As such, very few time lag studies regarding generational differences in work values have been conducted (Twenge, 2010).

Heterogeneity Within Generations

Gender, ethnicity and location all play a role in perceptions of a generation and lead to the probability of significant differences within a generation. Parry and Urwin (2011) use the example of how based on generations, the expectation is that women within one generation would have similar values as men, or how members of one generation are expected to be similar despite different levels of education. Lippmann (2008) identified clear differences between both males and females, as well ethnic groups in their experiences after being displaced. While investigating the civil right movements in the US, (Griffin, 2004) discovered that location had an impact on the collective memories of white women. Those who had first hand experiecnes of the problems while living in the southern US had stronger memories than white women of the same age living in different locations. All of these findings support Denecker, Joshi and Martochio (2008) conclusion that heterogeneity does add a challenge and complexity in defining generational groups.

If we consider political, historical and technological events in diferent countries, concerns arise defining generations, as much of the research to date has been done in the US. For example the Veteran generation can be seen as being heavily influenced by WWII and the Vietnam war, which has vastly different perceptions in different countries. It is very unlikely that individuals of the US and all other countries involved have been impacted or experienced these historical events in the same way. Consequently research regarding experiences of generations of the US cannot be simply superimposed onto experiences of other countries (Parry & Urwin, 2011). Hence academic literature proposes that generational characteristics in Eastern countries are not similar to Western. In this context, (Murphy, Gordon, & Anderson, 2004) investigated cross-cultural age and generational differences in Japan and the US. They result was significantcross-cultural age and cross-cultural generation differences between the two countries. As a result, when researching about generational differences on a global scale, the effects of nationality, ethnicity and gender must also be considered together with generational cohort (Parry & Urwin, 2011).

Contradictory Viewpoints of Results

A thorough review of existing literature revealed mixed conclusions towards the applicability of generational theory as the foundation of work value differences between generations and its applicability in management strategy. Therefore, in order to fully frame the context of this study, we must further explore this lack of consistency amongst existing literature.

Many previous studies and practical managerial literature conclude that both companies and managers need to be cognizant of the generational differences amongst their employees. Smola & Sutton (2002) conclude from their longitudinal study on work values that “companies must adapt practices and policies to respond to these changes” (p. 380), referring to changes their study found with regards to employees attitudes towards work centrality, and requirements for work life balance. Gursoy et al. (2013) suggest from the results of their study that managers and coworkers alike need to understand each other’s generational differences or else tensions among employees are likely to increase affecting job satisfaction and productivity (Kupperschmidt, 2000). Other studies have advised that managers who understand generational differences and the priorities of each generation are likely to create a workplace environment that foster leadership, motivation, communication and generational synergy (Gursoy et al., 2008; Smola and Sutton, 2002). Lancaster and Stillman (2002) suggest generational differences may have a substantial influence on workplace attitudes, and influence interactions between employees and managers, employees and customers, and employees and employees. Gursoy et al. (2013) further suggest that failing to manage generational differences in an effective way may increase turnover rate, losing valuable employees, and affect profitability. If not managed well, these differences can be a source of significant frustration for everyone in the workplace. Gursoy et al. (2013) even suggest that intergenerational training and mentoring programs may be required to identify generational gaps and enhance the opportunity of interaction between managers and employees from different generations.

Although there is little opposition to the idea of creating a workplace that promotes worker satisfaction, production, and enhances retention, the use of generational theory as its basis faces strong opposition. Despite suggesting multiple managerial strategies based off generational differences, Gursoy et al. (2013) do concede that some managers may view work values differences based on generation as superficial and may decide to ignore them. Through their thorough review of the existing literature Parry and Urwin (2011) found that “evidence is at best mixed, with as many [studies] failing to find differences between generations as finding them” (p. 88). Studies that were able to identify differences in work values, could not distinguish them from age being the possible driver or other factors in national context, gender or ethnicity. They suggest that given the multitude of problems inherent to the evidence on generational work value differences, that the value it provides to practitioners remains unclear, and suggest that the concept be ignored. Wong et al. (2008) found from their study that the results were not supportive of generational stereotypes that are common in managerial literature with few meaningful differences found. The factors contributing to the few differences their study did find once again could not be differentiated from age or career stage, echoing the results of Parry and Urwin (2011). Wong et al. (2008) found that their results “emphasize the importance of managing individuals by focusing on individual differences rather than relying on generational stereotypes which may not be as prevalent as existing literature suggests” (p. 878

1 Introduction

1.1 Research Problem

1.2 Research Purpose and Questions

2 Frame of Reference

2.1 Generational Theory

2.2 Work Values

2.3 Generational Work Value Differences

2.4 Age, Career Stage and Life Stage as Factors

2.5 Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies

2.6 Heterogeneity Within Generations

2.7 Contradictory Viewpoints of Results

2.8 Creation of Project Teams

2.9 Summary of Theoretical Framework

3 Research Method

3.1 Research Design and Method

3.2 Choice of Industry and Respondents

3.3 Data Collection

3.4 Ethical Considerations

3.5 Trustworthiness of Study

3.6 Data Analysis

4 Empirical Results

4.1 RQ1: Work Value Difference Recognition and Factors

4.2 RQ2: Work Value Influences

4.3 RQ3: Generational Considerations Creating Project Teams

5 Analysis and Interpretation

5.1 RQ1: Work Value Difference Recognition and Factors

5.2 RQ2: Work Value Influences

5.3 RQ3: Generational Considerations Creating Project Teams

5.4 Concluding Discussion

6 Conclusions

7 Limitations and Future research

7.1 Limitations of Study

7.2 Future Research

8 References

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT