Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

CHAPTER 3 HISTORICAL AND ECONOMIC POLITICS OF MINING AND CULTURAL CONTRIBUTION TO WOMEN AS MARGINALISED GROUPS IN SOUTH AFRICA

Mining’s tumultuous history evokes images of rootless, brawny and often militant men, whether labouring in the sixteen century in Peru or twenty first century in South Africa, but women are often ignored or reduced to shadowy figures in the background supporting male miner family members. Where were women in the mining world? (Mercier & Gier, 2007:995)

INTRODUCTION

Mining has been traditionally and ideologically constructed as a male space that disregards women and does not recognise the dynamic roles they could play in mining (Lahiri-Dutt, 2011). My research is unique in that it presents a parallelism of research on a mining environment as a traditionally constructed male-dominated space and board membership as a male-constructed occupation. As mining and boardrooms have long been characterised with masculinity, by its naturalised way of thinking and construction, mining does not embrace gender within the spectrum of mining. It does so by eliminating or hiding women and devaluing their agency as an important economic activity (Lahiri-Dutt, 2012:193). As discussed in Chapter 2, from an equality standpoint, this research began with a claim for an equal or balanced society in which there is a just distribution of power and resources, participation and influence between men and women (see Choudhury, 2014). In addition, the business importance of women as effective contributors in organisations is abundantly justified. In this chapter, I argue that TM on mining boards is in need of feminist scrutiny from an African perspective to expose and challenge the symbolism of mining boards as a masculine occupation of the working class and mining as the juggernaut with gendered impacts.

This chapter presents a review of the South African mining industry context, which is divided into five distinct sections. The first section provides a brief analysis of the economic relevance of South African mining. The second section justifies why the mining industry was chosen for analysis. The third section of this chapter focuses on demystifying how the historical and political environment of South Africa has shaped the mining industry as a male-gendered industry and occupation. The fourth section of this chapter focuses on understanding the legal context of equality and women in the South African mining sector by highlighting developments since the promulgation of the statutory and regulatory framework with efforts to improve the inclusion of women in this sector. The last section presents a review of the profiles of directors in the JSE-listed mining companies, which concludes this chapter.

THE RELEVANCE OF MINING TO THE ECONOMY OF SOUTH AFRICA

Mining constitutes 45% of the world economy (Cutifani, 2017) and still plays a critical role in the economy of South Africa, which contributes significantly to the world mining industry (Antin, 2013; Mining Indaba, 2018). South African mining companies dominate the global mining industry, and given the country’s competitive position in global mining, South Africa’s mining industry has been central to the economic growth and development of the country as one of the most naturally resource-rich nations in the world (Antin, 2013). Mining in South Africa’s economy accounts for 7.3% of the gross domestic product (GDP) directly (Chamber of Mines, 2016). Mining further accounts for around 60% of the country’s total exports by revenue (BMI, 2017). Mining contributes to fiscus through taxes and royalties, contributes 18% to private fixed investment and 11% to total fixed investment, and employs almost 8% of the private sector and almost 6% of employed people in South Africa (Chamber of Mines, 2016). The South African mining industry further contributes to direct employment, expenditure on resources produced by other sectors, such as agriculture, manufacturing, steel, banking (e.g. interest paid and insurance) and construction has created and sustained jobs for many people (Chamber of Mines, 2016). The South African mining industry is characterised by five major mineral categories, namely precious metals and minerals, energy minerals, metals and minerals, and industrial minerals (BrandSA, 2014). South Africa’s most important mineral reserves are gold, platinum, iron ore, copper, chrome, manganese, diamonds and coal. South Africa leads internationally as the largest producer of gold at approximately 4.4% of global gold production, having the third-largest gold reserves after Australia and Russia (Chamber of Mines, 2016). South Africa also leads in platinum and is one of the leading countries in the production of base metals and coal. Furthermore, the diamond industry of South Africa is the fourth largest in the world (BrandSA, 2014). In addition to the abundance of mineral reserves, South Africa is valued for its high level of technical and production proficiency as well as excellent research and development undertakings (BMI, 2017). South Africa’s economic industrialisation to secondary and tertiary industries and gold production has decreased over time (BrandSA, 2014). Although the industry’s contribution to the GDP has decreased (from 21% in the 1970s), mining remains the cornerstone of the South African economy in terms of foreign exchange earnings, tax and exports, fixed investment and employment activities (Baxter, 2015; Hamann, 2004). Statistics report contributions of 15% to foreign direct investment, 25% to exports and 1.4 million jobs in the country (BMI, 2016; 2017). Table 3.1 below shows a SWOT analysis of the South African mining industry.

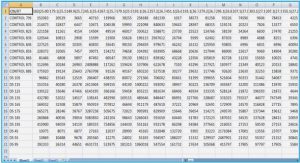

However, the industry faces several key challenges, such as a serious labour unrest due to reported unfair working conditions and labour shortages because of high turnover, requiring a strong commitment to the recruitment of new talent. According to BMI (2017), the South African mining sector is likely to face persistent headwinds due to labour conflict, a muted prices recovery, further divestments and retrenchments. This may affect the economy. Table 3.2 shows the unstable and somewhat decline of the mining value forecast, which is measured by economic profit and mining productivity.

Due to instability of the mining value forecast, innovation becomes critical to the future of mining. At the 2017 Mining Indaba, Cutifani (2017) stated that “we need to do things differently to find new safe, responsible and cost-effective ways to mine the ore bodies to meet the needs of a rapidly urbanising global population”. He added that a more resilient mining industry needs to be built, as well as responsible and collaborative partnerships as instrumental to redefining the future of mining (Cutifani, 2017). There is also a need for sustainable per-unit cost production, which can be realised by an increased level of productivity from all resources (PWC, 2012). Mining companies need to rethink the risk factors in the space in which they operate. Apart from health and safety matters, mining companies should integrate risk and performance management by evolving risk management in order to anticipate or plan for negative potential events (PWC, 2012). Subsequently, a vision and strong leadership from the BoD are required as per Companies Act of 28 (RSA, 2008) and it is necessary to reconsider key mining talent and labour issues specifically (PWC, 2012). Given women’s attentiveness to risk aversion and better governance, the mining sector is likely to benefit from increased representation of WoB.

WHY I CHOSE THE SOUTH AFRICAN MINING INDUSTRY FOR ANALYSIS

In this section, I justify why I chose the South African mining industry as an area of analysis. First, the mining industry remains the most male-dominated industry in the world. In South Africa’s unique history, the mining industry’s culture denotes the legacy of the historical effect on women and other previously marginalised groups (black people), where they were forbidden to partake in certain employment opportunities in this sector (Oliphant, 2018). As previously pointed out, the fall of apartheid in 1994 resulted in enforced compliance to redress, among other issues, the gender composition of the mining sector across all levels, including boardrooms (Botha, 2017). Due to the slow pace of transformation in South Africa (Booysen & Nkomo, 2006; Du Toit, Kruger & Ponte, 2008), particularly the poor representation of women in mining boards (Moraka, 2013), this industry is confronted with public scrutiny and faced with challenging public relations and a regulatory environment (Moraka & Jansen van Rensburg, 2015). As such, mining companies and their boards would be expected to be more proactive in managing their reputations to enhance stakeholder relations by focusing on equality in the workplace and eradicating inequalities.

CHAPTER 1 CONTEXTUALISING THE RESEARCH

1.1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

1.2 PURPOSE OF THE STUDY

1.3 PROBLEM STUDIED .

1.4 RESEARCH QUESTIONS

1.5 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

1.6 RESEARCH APPROACH

1.8 RESEARCH ETHICS

1.9 CHAPTERS OUTLINE

1.10 CHAPTER CONCLUSION

CHAPTER 2 GENDER EQUALITY AND TALENT MANAGEMENT IN WOMEN ON BOARDS RESEARCH

2.1 INTRODUCTION

2.2 TALENT MANAGEMENT IN WOMEN ON BOARDS STUDIES

2.3 A GLOBAL REVIEW OF WOMEN ON BOARDS RESEARCH

2.4 LEGISLATION (QUOTAS) AS A REMEDY FOR GENDER EQUALITY OF WOMEN ON BOARDS

2.5 THE BUSINESS AND THE EQUALITY CASE FOR WOMEN ON BOARDS

2.6 THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

2.7 FEMINIST THEORY

2.8 INTEGRATED THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

2.9 RECRUITMENT OF DIRECTORS

2.10 TRAINING AND DEVELOPMENT OF DIRECTORS

2.11 RETENTION OF DIRECTORS

2.12 CHAPTER CONCLUSION

CHAPTER 3 HISTORICAL AND ECONOMIC POLITICS OF MINING AND CULTURAL CONTRIBUTION TO WOMEN AS MARGINALISED GROUPS IN SOUTH AFRICA

3.1 INTRODUCTION

3.2 THE RELEVANCE OF MINING TO THE ECONOMY OF SOUTH AFRICA

3.3 WHY I CHOSE THE SOUTH AFRICAN MINING INDUSTRY FOR ANALYSIS

3.4 HISTORICAL POLITICS OF MINING AND CULTURAL CONTRIBUTION OF WOMEN AS MARGINALISED GROUP IN SOUTH AFRICA

3.5 THE LEGAL CONTEXT OF EQUALITY AND WOMEN IN MINING IN THE SOUTH

AFRICAN MINING INDUSTRY

3.6 THE STATUS OF THE DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE OF BOARDS IN THE MINING

SECTOR

CHAPTER 4 . RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

4.1 INTRODUCTION

4.2 RESEARCH APPROACH: AFRICAN FEMINIST RESEARCH

4.3 EPISTEMOLOGY: FEMINIST

4.4 METHODOLOGY: QUALITATIVE FEMINIST RESEARCH

4.5 METHOD

4.6 SAMPLING AND CASE SELECTION

4.7 RESPONDENT SELECTION

4.8 DATA COLLECTION

4.9 MY EXPERIENCE IN DOING THIS RESEARCH

4.11 LIMITATIONS AND STRENGTHS OF THE RESEARCH DESIGN ..

4.12 MEASURES TO ENSURE TRUSTWORTHINESS

4.13 CHAPTER CONCLUSION

CHAPTER 5 CASE A AND B ANALYSIS

CASE A

CASE B

CHAPTER 6 CASE C AND D ANALYSIS

CASE C

CASE D

CHAPTER 7 CASE E AND F ANALYSIS

CASE E

CASE F

CHAPTER 8 ,MULTIPLE CROSS-CASE ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

8.1 INTRODUCTION

8.2 TALENT MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ACROSS CASES

8.4 TRAINING AND DEVELOPMENT PRACTICES ACROSS CASES

8.5 RETENTION PRACTICES ACROSS CASES

8.6 CHAPTER CONCLUSION

CHAPTER 9 CONCLUSIONS, CONTRIBUTION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

9.1 INTRODUCTION

9.2 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

9.3 TALENT MANAGEMENT PRACTICES AT BOARD LEVEL

9.4 RECRUITMENT PROCESS AND CRITERIA FOLLOWED TO APPOINT FEMALE AND MALE DIRECTORS AND HOW AND WHY THE PROCESS DIFFERS BETWEEN FEMALE AND MALE DIRECTORS

9.5 INITIATIVES EMPLOYED FOR TRAINING AND DEVELOPMENT OF DIRECTORS AND HOW THEY DIFFER BETWEEN MALE AND FEMALE DIRECTORS

9.6 METHODS AND APPROACHES FOLLOWED TO RETAIN DIRECTORS AND HOW THEY DIFFER BETWEEN MALE AND FEMALE DIRECTORS

9.7 DAILY EXPERIENCES OF FEMALE DIRECTORS INFLUENCING THEIR RETENTION ON BOARDS

9.8 RESEARCH RECOMMENDATIONS (POLICY AND PRACTICE)

9.9 METHODOLOGICAL CONTRIBUTIONS

9.10 MY PERSONAL REFLECTIONS …

LIST OF REFERENCES

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT