Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Characteristics of the studies under review

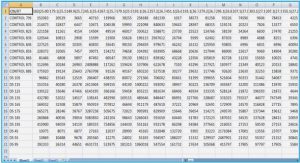

As the findings of empirical studies tend to be idiosyncratic according to the research methodology (Leonidou et al. 2002), it is essential to examine the methodological aspects of the studies included in this review. The design of our literature review is inspired from Sousa’s (2004) literature review on the international performance measurement for describing the characteristics of the studies reviewed. Similar to the study conducted by Sousa (2004), the studies were evaluated in terms of: (1) fieldwork characteristics (country of study, industrial sector, and firm size), (2) sampling and data collection (sample size, data collection method, response rate, non-response bias, key informant, and units of analysis), (3) statistical analysis, and also added are (4) theoretical considerations (the use of a grounded theory for explaining the research model and the use of research hypothesis or research propositions). Table 1 from Appendix 1 summarizes the descriptive properties of the 37 studies selected for review purposes.

It is worth to note that the analysis was not exclusively limited to the studies undertaken on SMEs (as defined in the previous section I.1) for mainly three reasons. The first reason is that there are not many studies conducted in the field. The second reason is that even though they did not specifically aim to focus on SMEs, it can be observed from the sample composition that there are mostly SMEs in each sample of the reviewed studies. The third reason is that the definition of SMEs varies along the geographical location of the studies. For example, a study conducted in the United States of America (U.S.A.) will account for enterprises with less than 500 employees for SMEs, whereas in Europe, SMEs are considered to have less than 250 employees.

Although most research on the impact of export information-related behaviors on international performance was conducted in the U.S.A., an increasing number of studies have been carried out in other countries. Of the studies reviewed, 10 took place in the U.S.A., followed by Canada and the United Kingdom with six, and New Zealand, the Netherlands, France, China and Austria with two studies each. In the following countries a single research study has been conducted: Scotland, Denmark, Norway, Cyprus, Brazil, Costa Rica, El Salvator, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Sweden, Belgium, Switzerland, Norway, Sweden, Australia, Chile, Turkey and Finland.

Three important observations have to be made about the geographic focus of the studies under review. First, five of the studies reviewed conducted their research by collecting data from more than one country. The study of Dominguez and Sequiera (1993) collected data from Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua. The authors did not check for cross cultural differences in terms of information behaviors from one country to another but instead assumed that these South American countries are characterized by a homogeneous cultural basis. The study of Seringhaus (1993) was conducted in Canada and Austria. Seringhaus (1993) checked for cross-country differences in terms of firms’ export information behaviors. In addition, both studies, namely the one of Souchon and Durden (2002) and the one of Voerman (2003) were conducted in more than one country. The study of Souchon and Durden (2002) was conducted in New Zealand and the U.K. The study of Voerman (2003) exploited data from Austria, Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Norway and Sweden. Voerman (2003) checked for cross-cultural differences regarding export information behaviors of firms among these countries. The study of Morgan et al. (2003) was conducted in China and the U.K; the authors tested their research model in both countries without exploring specifically for cross-national differences. Second, the bulk of the research was conducted in more developed countries perhaps because most researchers were affiliated with institutions based in these countries. Third, 11 studies restricted their analysis to specific regions within a given country. Five of the “regional studies” were conducted in the U.S.A., three in Canada, and one in Brazil (Sao Paolo area), France (eastern France) and in the U.K. (Welch).

The vast majority of the 37 reviewed studies involved samples drawn from multiple industrial sectors and put emphasis on the manufacturers or industry rather than consumer products. Only two studies focused on firms representing one industrial sector, namely the machine tool industry (MacPherson 2000), and the textile industry (Akyol and Akehurst 2003). Four other studies concentrated on two or three industries. Only one study specifically addressed the high-tech firms (Seringhaus 1993). The last approach allows for the control of industry-specific influences such as the type of product or level of technology.

Studies conducted in the 1980’s generally tended to use relatively small sample sizes sometimes with fewer than 50 firms. The size of the samples used in the reviewed studies ranges from 39 to one 1112 (the study of Voerman 2003, which can rather be seen as an exception). The average sample size is 176,852 (standard deviation = 99,58, and median = 175). One should note that only 24 studies have used samples greater than 100 observations and seven studies used samples with 50 or less observations. Overall, sample sizes are larger in more recent studies in comparison to prior research.

The overwhelming majority of the 37 studies reviewed relied on postal data collection (33 studies). This number can be partly explained by the difficulties in physically reaching firms that are geographically dispersed. These difficulties are exacerbated in the case of cross-cultural studies where firms are located in different countries. Three studies employed personal interviews instead of a mail survey in order to collect data mainly to solve problems of distrust and access to respondents and in order to increase response rate due to the length of the questionnaire. Additionally, personal interviews are generally more appropriate for gaining deeper insight into the problem though more appropriate for exploratory and sometimes descriptive research. Personal interviews also provide a better alternative to surveys in terms of data reliability (Cavusgil and Zou 1994). In one study, the questionnaire was administered by fax (MacPherson 2000).

The studies reported response rates ranging from 10,7% to 88%. The average response rate is 34,32% (standard deviation = 15,63 and the median = 26%). In the case of cross-cultural studies, the average response rate was above 20%. An important number of studies did not check for non-response bias. Only 19 studies tested the non-response bias and one study provided rather unclear information concerning this matter. The study of De Luz (1993) was the only one that explains that on a descriptive basis, it seems that the characteristics of the enterprises interviewed are similar to the one in the total study population.

Since information is a “key ingredient” for successful decision-making, management should be considered a major force behind the initiation and development of firms’ information activities (Miesenbock 1988). Sixteen out of the 37 studies did not identify their source of information. Two of the studies by Ramangalahy (2001) and Spence (2003) did not provide clear information on this issue. For instance, Ramangalahy (2001) explained that the questionnaire was addressed to the manager of the company but failed to provide any additional information about the real respondents. In most studies, data was collected from the CEOs or the export managers (in six studies) or from the executives responsible for exporting activities or the marketing directors (in five studies). Less often, respondents are other executives of the company. Even though the general manager of the company frequently makes export decisions, the tendency to view firms as having only one decision-maker is misleading since decisions are often made by more than one person in the company (Leonidou and Katsikeas 1997).

The information processing specificity characterizing SMEs with respect to their larger counterparts is a generally accepted idea among scholars. Large firms generally have more resources to allocate information gathering and dissemination activities (Samiee and Walters 1990; Denis and Depelteau 1985; Crick et al. 1994). Despite this generally admitted idea, 17 of the reviewed studies provided no information concerning the firm size or any clear information. Of the nine studies that reported the size of the firm, most focused on the relationship between export performance and export information behaviors of small to medium-sized firms (SMEs). This can be partly attributed to the fact that smaller to medium-sized firms play an important role in many economies since they often account for the largest part of the industrial base. Moreover, SMEs present specificities in terms of information processing behaviors (as it was already previously explained). Eleven studies addressed all ranges of sizes of firms and only the study of Boutary (1998, 2001) addressed only middle-sized firms; she defined the middle enterprise arbitrarily according to its size ranging from 100 to 200 employees. In relation to the firm size, only two important points are worth mentioning. First, the definition criteria differed among the studies (e.g. number of employees, annual sales). Second, because of the geographic focus of these studies, the meaning of the terms “small”, “medium”, and “large” varies greatly in an international context. In the U.S.A., SMEs account for less than 500 employees, whereas in the E.U. SMEs have been defined as having less than 250 employees since 1996. It can nevertheless be observed that in spite of the official definitions, some studies chose other criteria in terms of size. MacPherson (2000) mainly targeted firms with less than 20 employees and Boutary (1998, 2001) studied firms that had from 100 to 200 employees. Alvarez (2004) did not consider micro-firms within his analysis.

Most of the studies reviewed used the firm as the unit of analysis. In the case of using the firm as the unit of analysis, the export performance is assessed in the context of the firm’s overall activities in international markets. This assessment of the international performance can be attributed to the greater willingness of key informants to disclose information at this broad level (Matthyssens and Pauwels 1996). This approach challenges the argument of Cavusgil and Zou (1994) and Cavusgil et al. (1993) in that the proper unit of analysis in export performance research should be the export venture as a single product or product line exported to a single foreign market. Firms may have more than one product line, and each of them may have different effects on export performance and the information activities carried out in foreign markets with this respect. Only two studies adopted export venture as the unit of analysis, namely the study of Madsen (1989) and the study of Cadogan et al. (2002). The study conducted by Rosson and Ford (1982) took the relationship between suppliers and foreign distributors as the level of analysis.

In comparing the principal method of analysis of the latest studies with older studies from the 1980’s, one can observe that the level of statistical sophistication has changed. The majority of the more recent studies after 1995 use multivariate data analysis techniques such as factor analysis, cluster analysis, discriminant analysis, multiple regression analysis, and structural equation modeling (SEM). Mainly descriptive statistical techniques such as correlation and analysis of variance, T-tests, and Chi Square were employed more extensively in the early stages. Despite the other methods of analysis, descriptive statistical methods prevail. Only 18 studies used explicative statistical techniques as regression analysis or SEM.

Among the reviewed studies, only three studies (Hart et al. 1994; Souchon and Diamantopoulos 1997; Walliser and Mogos-Descotes 2004) declare themselves as exploratory. However, the majority of the studies (19 studies) use descriptive statistics techniques.

Only 20 of the studies reviewed used research hypothesis. This relatively reduced number may also be explained by the exploratory nature of most of the studies. Out of the 37 studies reviewed, only three studies used a theory for grounding the research hypothesis. Of the three studies, two relied upon the resource-based view (RBV), namely the study of Ramangalahy (2001) and Julien and Ramangalahy (2003), and one used insights from the knowledge-based view of the firm (KBV), the study of Morgan et al. (2003).

It is worth to note that the number of studies specifically addressing the link between export performance and export information behaviors is reduced. During the last 26 years, only 16 studies have focused specifically on the relationship between international performance and firms’ export information behaviors. The remaining studies addressed the relationship between export performance and export information rather periferically as a part of a more general research question.

Several of the studies specifically addressed the acquisition or use of export information by means of export assistance (Donthu and Kim 1993; Weaver et al. 1998; Diamantopoulos and Inglis 1988; Gencturk and Kotabe 2001; Spence 2003; Alvarez 2004; Wilkinson and Brouthers 2006) while three other studies focused on the export marketing research practices of enterprises (Cavusgil 1884a; Bijmolt and Zwart 1994; De Luz 1993). Additionally, other studies concentrated exclusively on export market intelligence practices (Mac Pherson 2000; Rosson and Ford 1982). Three of the reviewed studies pertain to the export market orientation literature, namely the studies of Cadogan et al. (2002), Akyol and Akehurst (2003), and Cadogan and Cui (2004). Finally, the rest of the reviewed studies addressed general export information related activities without highlighting specifically certain export information acquisition techniques.

The opperationalization of the main constructs of the study: export information-related constructs and international performance

In this section, the way export performance and export information-related activities have been studied and operationalized will be further explained.

International performance measurement

Based on Table 1, one can see an evolution of the export performance measures over the years. Older studies generally only use objective or absolute measures of international performance such as the export sales ratio and export sales ratio growth. Studies that are more recent use both objective and subjective measures. Examples of subjective measures are the perceived progression of foreign sales profits compared to domestic markets, the perceived overall export development, the general satisfaction with exporting activities or the perceived achievement of strategic exporting goals, etc.

In the 1980s, objective measures were prevalent yet nowadays some scholars support the use of subjective over objective indicators (e.g. Katsikeas et al. 1997; Robertson and Chetty 2000). Scholars argue this preference by the facts that: (1) firms are reluctant to provide the objective data (Francis and Collins-Dodd 2000; Leonidou et al. 2002); (2) objective data is sometimes difficult to access, and thus it is uneasy to check for the accuracy of the reported financial export performance figures (Robertson and Chetty 2000), (3) managers are mainly guided by their subjective perceptions when making decisions (Madsen 1989), etc.

The general agreement among researchers is that both types of measures are equally important and should be used given the advantages of each of the two approaches and their complementary nature (Shoham 1998; Sousa 2004). Nonetheless, international performance measures generally vary from one study to another, making the comparison of the findings of different studies difficult.

The operationalization of the most widely used measures for capturing information related activities

The most commonly used measures for describing the use of information and information sources are their frequency of use and their perceived importance. The frequency of use of information sources was measured as a nominal variable with four modalities, which were “never”, “seldom”, “about twice a year” and “others” in Moini’s (1995) study; as a nominal variable with five modalities (“less than once a year”, “once or twice a year”, “three to four times a year”, “from six to ten times a year”, “more than ten times a year”) in Weaver et al.’s (1998); as a nominal variable with four modalities in Koh’s (1991) study (“none at all”, “less than once a year”, “once a year”, and “more than once a year”). Other studies assessed the frequency of use of export information as a subjective measure, operationalized as an interval variable measures on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 = “rarely” to 5 = “very often” in Leonidou and Katsikeas’s (1997) study, as an interval variable, measured on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 = “never undertaken” to 4 = “always undertakes”; as an interval variable in Seringhaus’s (1993) study, and also as an interval variable measured on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 = “never use” to 5 = “always use” in Yeoh’s study (2000). One can notice the six different operationalizations in six different studies. Thus, it can be concluded that researchers have not yet reached an agreement on what exactly a frequently used information source is.

Another common measure within the literature is the perceived usefulness of information sources. Weaver et al. (1998) assessed the perceived helpfulness of governmental financial services. Similar measures were also used in other studies. Such examples are the perceived criticality of information sources, assessed on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 = “no importance” to 5 = “critically important” (MacPherson 2000), and the perceived importance of information sources, assessed on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = “not important” to 5 = “very important” (Leonidou and Katsikeas 1997; Julien and Ramangalahy 2003; Walliser and Mogos-Descotes 2004), etc. Cavusgil (1984a) assessed the perceived importance of foreign market research by means of comparison with the domestic market research. He used a nominal measure with three categories that included “much less important than domestic market research”, “less important than domestic market research” and “equally important to domestic market research”.

Table of contents :

INTRODUCTION

1 The relevance of the research question

1.1 Academic relevance

1.2 Managerial relevance

1.3 Relevance for policy-makers

2 Dissertation structure

PART I. LITERATURE REVIEW

CHAPTER I. THE IMPACT OF EXPORT INFORMATION UPON THE INTERNATIONAL PERFORMANCE OF SMEs. EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

I.1 Defining exporting SMEs

I.1.1 SMEs’ specificities

I.2 The empirical evidence concerning the link between export information and international performance

I.2.1 The scope of the review

I.2.2 Characteristics of the studies under review

I.2.3 The opperationalization of the main constructs of the study: export information-related constructs and international performance

I.2.3.1 International performance measurement

I.2.3.2 Export information study and measurement

I.2.3.2.1 The operationalization of the most widely used measures for capturing information related activities

I.2.3.2.2 Proposing a classification of the different export information related measures

I.2.3.2.3 Taxonomies of export information acquisition and use

I.2.4 The link between international performance and export information

I.2.4.1 The relationship between export information sources (acquisition and use) and international performance

I.2.4.1.1 The relationship between export assistance and international performance

I.2.4.1.2 The relationship between export market research and international performance

I.2.4.1.3 The relationship between export market intelligence and international performance

I.2.4.2 The relationships between other measures used to capture export information related behaviors and international performance.

I.2.4.3 The relationship between the acquisition of different information elements on foreign markets and international performance

I.2.4.4 The studies examining the indirect relationship between information acquisition, its use and international performance

I.2.5 Discussion

I.2.5.1 Methodological shortcomings and future research avenues

I.2.5.2 Theoretical shortcomings and future research avenues

I.2.5.3 Operationalization shortcomings and future research avenues

I.2.5.3.1 Shortcomings in terms of international performance operationalization

I.2.5.3.2 Shortcomings in terms of export information acquisition and use opperationalization

I.2.5.3.3 Shortcomings of the study of the relationship between the behaviors in terms of export information acquisition and use and international performance

CHAPTER II. A SYNTHESIS OF THE MAIN THEORETICAL ADVANCES DESCRIBING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN INFORMATION AND PERFORMANCE

II.1 Defining information

II.1.1 Syntactic and semantic aspects of information

II.1.2 The distinction between information and knowledge

II. 2 The main theoretical frameworks explaining the link between information and organizational performance

II.2.1 Contingency theory

II.2.2 Decision-making theory

II.2.3 Resource based view of the firm

II.2.4 Entrepreneurial theoretical advances

II.2.5 Organizational learning theory

II.2.6 Market orientation theoretical advances

II.2.6.1 The two conceptualizations of organizational market orientation

II.2.6.2 From market orientation to market-based learning

II.2.6.3 Market orientation theoretical advances

II.3 Critical analysis of the theoretical frameworks explaining the link between information and organizational performance

II.3.1 Converging aspects of the theoretical frameworks reviewed

II.3.1.1 Information quality or richness

II.3.1.2 The organizational mechanisms necessary to improve information dissemination within organizations

II.3.2 Diverging aspects of the five theoretical frameworks reviewed

II.3.2.1 Main focus, organization’s conceptualization and organizational performance sources

II.3.2.2 The different theses proposed on the relationship between information and organizational performance

II.3.3 Critical analysis of the theoretical frameworks reviewed

II.3.3.1 Towards an integrative theoretical framework over the impact of information activities on organizational performance

II.3.3.2 Absorptive capacity, a suitable perspective for looking at the relationship between information activities and organizational performance

II.4 Absorptive capacity: a dynamic capability enhancing organizational performance

II.4.1 Potential and realized absorptive capacity and their link to organizational performance

CHAPTER III. THE RESEARCH MODEL DEVELOPMENT

III.1 The impact of PACAP’s antecedents on the Potential Absorptive CAPacity (PACAP)

III.1.1 The conceptualization of PACAP’s antecedents and PACAP

III.1.1.1 PACAP’s antecedents conceptualization

III.1.1.1.1 The exposure to rich export information sources

III.1.1.1.2 The previous international experiences of the firm

III.1.1.2 PACAP conceptualization

III.1.1.2.1 Export information acquisition dimension

III.1.1.2.2 Export information assimilation dimension

III.1.3 The impact of PACAP’s antecedents upon PACAP development

III.1.3.1 The impact of SMEs’ exposure to rich export information sources on export information acquisition

III.1.3.2 The impact of SMEs’ international experiences richness on export information acquisition

III.2 The impact of PACAP on RACAP (Realized Absorptive CAPacity) development

III.2.1 RACAP conceptualization

III.2.1.1 Conceptualization of the transformation dimension of RACAP: the export responsiveness of SMEs

III.2.2.2 Conceptualization of the exploitation dimension of RACAP: the competitive advantage in terms of international marketing competences of SMEs

III.2.2 The influence of PACAP on RACAP

III.2.2.1 The impact of PACAP on the transformation dimension of RACAP

III.2.2.1.1 The impact of the export information acquisition on the export responsiveness of SMEs

III.2.2.1.2 The impact of the information assimilation on the export responsiveness of SMEs

III.2.2.2 The impact of SMEs’ international experiences and export responsiveness on the exploitation dimension of RACAP

III.2.2.2.1 The impact of the international experiences of SMEs

III.2.2.2.2 The impact of the export responsiveness of SMEs

III.3 The impact of RACAP on the international performance of SMEs

III.3.1 The impact of RACAP’s transformation dimension

III.3.2 The impact of RACAP’s exploitation dimension

CHAPTER IV. CONSTRUCTS OPERATIONALIZATION

IV.1 The antecedents of PACAP

IV.1.1 Operationalization of the exposure to information sources

IV.1.2 Operationalization of the experiential dimension

IV.2 PACAP dimensions

IV.2.1 Operationalization of the information acquisition dimension

IV.2.2 Operationalization of the information assimilation dimension

IV.3 RACAP dimensions

IV.3.1 Operationalization of the transformation dimension of RACAP

IV.3.2 Operationalization of the exploitation dimension of RACAP

IV.4 The dependent construct: the international performance of SMEs

IV.5 Operationalization of the control variables

CHAPTER V. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

V.1 The level of analysis: the firm

V.2 The results of the preliminary qualitative research

V.2.1 Results of the interviews realized with the Romanian enterprises

V.2.1.1 Export information acquisition

V.2.1.1.1 Information sources consulted on foreign markets

V.2.1.1.2 Export information elements acquired on foreign markets

V.2.1.2 Export information use

V.2.1.3 The factors enhancing export information exploitation (managerial perspective)

V.2.1.4 The practices enhancing export information use within firms

V.2.1.5 Proposition of a classification of Romanian enterprises based on their international experience

V.2.1.6 Other aspects

V.2.2 Results of the interviews realized with the French enterprises

V.2.2.1 Export information acquisition

V.2.2.1.1 Information sources consulted on foreign markets

V.2.2.1.2 Export information elements acquired on foreign markets

V.2.2.2 Export information use

V.2.2.3 The factors enhancing export information exploitation (managerial perception)

V.2.2.4 The practices enhancing information use within firms

V.2.2.5 Other aspects

V.2.3 General conclusions relative to the export information management by exporting companies from France and Romania. A comparative analysis

V.2.3.1 Export information acquisition

V.2.3.2 Export information use

V.2.3.3 The factors enhancing export information exploitation (managerial perspective)

V.2.3.4 The practices enhancing export information assimilation within firms

V.2.3.5 Other aspects

V.2.3.6 General conclusions impacting the research design

V.3 Questionnaire development

V.3.1 The “qualitative” questionnaire pre-test

V.3.2 The “quantitative” pre-test of the knowledge transfer and integration scale

CHAPTER VI. QUESTIONNAIRE ADMINISTRATION AND DESCRIPTIVE RESULTS

VI.1 Questionnaire administration

VI.2 Descriptive analysis of the results

VI.2.1 Sample description

VI.2.2 PACAP’s antecedents

VI.2.2.1 International experiences

VI.2.2.2 Export information sources richness

VI.2.3 PACAP levels

VI.2.3.1 Export information acquisition

VI.2.3.2 Assimilation practices

VI.2.4 RACAP levels

VI.2.4.1 Export responsiveness

VI.2.4.2 The positional advantage in terms of international marketing competences

VI.2.4 The levels of international performance

VI.2.5 The control variables

VI.2.6 Synthesis of the descriptive analysis

VI.3 Measurement model validation

VI.3.1 The psychometrical properties of the dependent variable: the international performance of SMEs

VI.3.2 Outer model estimation

CHAPTER VII. RESEARCH PROPOSITIONS’ TEST, CONCLUSIONS, LIMITATIONS, IMPLICATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH AVENUES

VII.1 Research propositions’ test, results, discussion

VII.1.1 The impact of PACAP’s antecedents on PACAP

VII.1.1.1 The impact of the richness of export information sources upon export information acquisition

VII.1.1.2 The impact of the international experiences of SMEs upon export information acquisition

VII.1.1.3 Synthesis of the results of the research propositions concerning the impact of PACAP’s antecedents upon PACAP levels of SMEs

VII.1.2 The impact of PACAP on RACAP

VII.1.2.1 The impact of the determinants of the transformation dimension of RACAP (SMEs’ export responsiveness capacity)

VII.1.2.1.1 The impact of export information acquisition

VII.1.2.1.2 The impact of export information assimilation

VII.1.2.1.3 Synthesis of the results of the research propositions concerning the impact of PACAP upon RACAP’s transformation dimension

VII.1.2.2 The impact of the determinants of the exploitation dimension of RACAP (the positional advantage in terms of international marketing competences of SMEs)

VII.1.2.2.1 The impact of the SMEs’ international experiences

VII.1.2.2.2 The impact of the SMEs’ responsiveness capacity

VII.1.2.2.3 Synthesis of the results of the impact of the determinants of RACAP’s exploitation dimension

VII.1.3 The impact of RACAP on SMEs’ international performance

VII.1.4 Global evaluation of the research model

VII. 2 Conclusions, limits, research contributions and avenues for future research

VII.2.1 The main objectives, main theoretical and methodological choices of the current research

VII.2.2 Synthesis of the results

VII.2.3 Research contributions and implications

VII.2.3.1 Theoretical contributions and implications

VII.2.3.2 Methodological contributions and implications

VII.2.3.3 Research contributions and implications for managers

VII.2.3.4 Research contributions and implications for policy makers

VII.2.4 Limits and future research avenues

VII.2.4.1 Theoretical limits and prolongations

VII.2.4.2 Methodological limits and prolongations

VII.2.4.2 Limits and prolongations related to the results of the research

BIBLIOGRAPHY