Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

How to capture place brand equity? The case of Sud de France

Summary

Within a globalised and highly competitive economy, the development of place brands has become important for cities, regions and countries. However, there is still little evidence about the conceptualisation and measurement of their performance. In order to contribute to the current discussion of place brand equity, we analyse the effects of a branding initiative in the South of France. According to the collective aspects of the place brand concept, we propose a multi-dimensional approach through qualitative interviews with various stakeholders and a review of secondary, mainly statistical data. Findings indicate that several factors are crucial for capturing equity of place brands. First, their collective character, involving different stakeholders, second, the fact that they generate economic and non-economic outcomes, third, their dependence on a socio-political and macro-economic context and fourth, the time they need to establish. All these constituents require a more holistic approach to capture place brand equity than usual brand equity definitions for companies. Results also suggest that if place brands aim at long-term development of places, estimating their overall value can be based on evaluation logics for public development interventions, which are easily feasible, time and cost saving and fulfil the need for accountability for governmental institutions.

Introduction

Brand equity aims to define the value of a brand. As brands are intangible assets, one deals with a complex issue and faces a diversity of definitions and measurement methods in marketing literature as well as from practical accounting side (Kapferer 2008, Wood 2000).

Traditional academic approaches to brand equity build on either product-consumer relations (Aaker 1996, Keller 1993) or concentrate on financial impacts of a brand on the performance of individual companies (Simon & Sullivan 1993). The consumer-oriented definition of brand equity can be sub-divided into two perspectives. The first one measures mental brand equity, i.e. the impact of the brand on the consumers’ consciousness (brand associations, awareness and perceived quality). The second one investigates the consumers’ behavioural response to the brand (loyalty, purchase intention, commitment). On the contrary, a company-based approach analyses the added value to a firm in terms of money and draws on financial and economic indicators such as profit, turnover, cost-benefit ratio and market share as effects of branding. More recent approaches, mainly coming from business-to-business or services marketing, focus on brand equity achieved through consumer or customer relationships (Berry 2000, De Chernatony & Segal-Horn 2003, Grönroos 2001).

Kapferer (2008) points out that many practices of brand equity measurement only use one or two of the above sets of indicators (e.g. brand awareness, or loyalty, or market share). They don’t take into account other important aspects, such as the time factor (evolution of brands), competitors, marketing-mix, possibilities of brand or geographical extensions etc. Apart from these shortcomings, another critical point is that different methods may relatively well determine the brand value of individual companies, but may be largely insufficient to measure brand equity for places. We argue that place brands require different assessment approaches and other performance measurements than company brands.

This article is based on a case study of the brand Sud de France in the region Languedoc-Roussillon (South of France) and focuses on the evaluation of place brand equity in relation to the regional branding strategy. We outline the theoretical background and methodology. Then the case study is presented, followed by analysis and discussion.

Theoretical background

It has been highlighted in place brand literature that place brands are complex and difficult to control (Braun & Zenker 2010, Kavaratzis 2005, Moilanen & Rainisto 2008). Several reasons are put forward in literature. First, place brands involve different public and private partners and aim at diverse target groups. Therefore, neither a dyadic product-consumer nor a company-customer perspective seems to be sufficiently elucidative. An assessment of place brand equity rather should take into account effects on different stakeholder groups. Stakeholders are defined as “any group or individual who is affected by or can affect the achievement of an organisation’s objectives” (Freeman 1984: 46). Stakeholder theory is based on the assumption that a firm’s performance not only depends on direct business relationships, but also on relations with a wide range of people and organisations, such as media, NGOs, the public opinion or even competitors. Studies of multi-stakeholder processes (Hankinson 2004, Morgan et al. 2003) suggest that success is achieved by the involvement of various stakeholder groups acting within a spatially bounded area. Until now, literature dealing with ‘country equity’ has focused on country images and perceptions by the consumer, explaining consumer preferences for products of their own or another specific country (Dinnie 2004, Papadopoulos & Heslop 2002, Verlegh & Steenkamp 1999). A second reason for the unpredictable outcomes of place brands is that these are umbrella brands (Iversen & Hem 2008). They can cover a wide range of tangible and intangible assets, such as natural and cultural sites, local products and tourism services. Umbrella brands also give options for brand extensions. This generally may lead to multiple and different outcomes and interpretations. In his stakeholder-brand value model, (Jones 2005) shows that outcomes of a brand cannot be conceived by one single criterion or measure, as they are of quite different nature. He lists possible outcomes in addition to profitability, such as reputation, synergy or political influence. A third reason is related to functions of place brands as policy instruments (Anholt 2008, Van Ham 2008). They can be used to manage place identity and reputation and as communicators for lifestyles, norms and values (Van Ham 2008). They may also serve as strategic tools for local development of places, attracting tourists, companies and skilled people, or enhancing export opportunities for local firms. Therefore, a measurement of place brand equity should bear in mind the socio-cultural, economic and political context of a place. Its characteristics influence its general competitiveness as well as the management and outcomes of a branding initiative (Kotler & Gertner 2002, Rainisto 2003). Fourth, place brands adopt a broader perspective and longer time horizon than single companies’ brands. Although both seek to achieve competitive advantages and value increase, place brands particularly aim to encourage long-term development processes of places. This may include the creation and maintenance of local employment, or the protection and valorisation of intangible assets, i.e. historical, cultural or natural assets. Place brands are expected to offer an opportunity to “contribute above and beyond that tired old litany of ‘increasing shareholder value’… to create a fairer distribution of the world’s wealth” (Anholt 2004: 17). Finally, it could be noted that place brands are often used by firms in association with other collective or individual brands.

These reasons motivated us to use an in-depth case study and to propose a multi-dimensional approach that addresses the complexity of place brand equity. The relevance of this attempt was also confirmed by policy makers and place managers. Chantal Passat, responsible for the agri-food sector of Sud de France Development – an organisation which coordinates all activities related to the brand Sud de France – stated in an interview that:

“The regional government continuously asks me about the economic impact of Sud de France on local food enterprises. But I don’t have indicators, and enterprises are too busy to analyse their internal sales figures while differentiating between collective brand, own brand, or no brand… So what I really need to kn ow is how to measure the value of this brand.” (Interview 14 June 2013)

By analysing the effects of the Sud de France branding strategy, we aim to contribute to the current discussion of place brand equity and to review the assumptions above. This case study allows gathering and sharing new insights about possible outcomes and working mechanisms of place brands as well as propositions for their evaluation.

Methodology

For the Sud de France case, we propose to evaluate place brand equity by analysing various effects of the regional brand on different stakeholder groups and the place as a whole. As place brands are usually initiated by the public sector, we seek to answer three questions which normally are used to evaluate development intervention impacts (Ton 2012, Ton et al. 2011):

– Does it work? What positive and negative effects/changes does the place brand generate for regional stakeholders?

– How does it work? What mechanisms of the brand generate intended or unintended effects, for whom, and under which conditions?

– Will it work elsewhere? What elements might work for whom under which conditions?

We offer a multi-dimensional approach to place brand equity through evaluations by various stakeholders on the one hand and a review and an analysis of secondary, mainly statistical data on the other hand. Thirteen semi-structured interviews documented the various perceptions and expectations of public and private actors within the regional system. The interviews were triangulated with secondary data, i.e. press and academic articles, internet sites and policy documents. The case study reflects individual opinions as well as broader developments taking place through and in the context of the branding initiative. In order to highlight the background, we briefly present the origin, objectives and strategy of the brand, then identify the main stakeholders involved and finally analyse the brand effects.

This allows gaining new insights about the effects and working mechanisms of place brands – including information about their potential and limitations – and propositions for an overall evaluation.

Main results: the Sud de France case

Languedoc-Roussillon is one of the 27 regions in France, situated in the South and bordered by the Mediterranean Sea, with Montpellier as capital. Geography and culture within this region are highly contrasting, and its economy is still the lowest of all French metropolitan regions, with a high percentage of unemployment (13,5% in 2012). Two key economic sectors are tourism and agriculture; Languedoc-Roussillon is the world’s largest wine producing region. Compared to other regions in the Midi like Provence or Côte d’Azur, Languedoc-Roussillon remained relatively unknown for a long time, despite its beautiful landscapes, cultural heritage (such as the Pont du Gard or the medieval city of Carcassonne), hundreds of kilometres of coast and enormous wine production.

Origin, objectives and strategy of the brand

The former president of the region, Georges Frêche(2004-2010), wished to create a common regional identity, to bring the region out of its seclusion, to activate resources for internationalisation and to participate in major economic markets. So, he initiated a collective territorial brand called Septimanie, inspired by the historical name of the area during the period of the Visigoths. But Septimanie was a flop, facing vehement resistance from the Catalonian part of the region, who saw this name as damaging their identity (Molenat online document 2005). After this failure, Sud de France was launched in 2006. The intention of this brand name was to evoke positive associations with French cuisine in general, with the sun and the South – already renowned abroad because of Provence and the Côte d’ Azur – in particular. It was initiated in a time of economic crises where especially small firms had difficulties to expand. Even though Sud de France was firstly intended to be a common export label for wine companies, it was immediately extended to other agri-food chains and in 2008 to tourism services.

Since its beginning, the marketing strategy focused strongly on international export of local products, mostly wine, as well as on promotion of the region in general, supported by large advertisement campaigns financed by the regional government (about 15-18 million Euros yearly, Manceau online document 2010)10. The promoted image is constructed upon values of the Mediterranean art of living, as an expression of a convivial lifestyle, with authentic, diverse, tasty, healthy food and wine. The image combines tradition with modernity.

Entrance criteria for using the brand are defined in different catalogues of specifications, depending on category (wine, food or tourism services). Contrary to tourism, where high quality is demanded and controlled via an external audit, the access for food producers has until now not been very strict. After several problems concerning food provenance and quality – e.g. products originating from Spain were sold under the Sud de France label – the quality book was re-edited in 2013 in order to achieve a higher level of specifications. This repositioning was done with caution, as it may lead to an exclusion of small producers or companies (Interview C. Passat, 14 June 2013). Using the brand doesn’t offer a direct price premium for producers – as French foodstuffs are already highly priced and therefore less competitive at international level – but other advantages, as presented below in the interviews.

In 2013, the umbrella brand brought 7,800 different agricultural products and 774 quality tourism services under its banner, from more than 2,600 members (varying from wine and food producers, food enterprises, hotels, restaurants, to local tourist offices). In addition, Sud de France is also used as an institutional brand, associated with, amongst others, sport and cultural events, the universities of Montpellier and Perpignan or the Sète harbour.

10 This is not an official figure from the regional government, who was not willing to communicate the exact amount.

Governance structure and stakeholders involved

As brand owner, the regional government (La Région Languedoc Roussillon) plays a directive role in the implementation of the brand. It finances and governs the brand, and gives licenses to its users. All Sud de France related activities of different private users from the wine, food and tourism sectors are coordinated by Sud de France Development. This organisation defines collective strategies for distribution, export and business development, ensures the worldwide promotion by special Sud de France Festivals and assists the enterprises in their internationalisation. It also plays a strategic role as interface between producers and buyers, principally large retail groups. In addition, Sud de France Development is responsible for the international stores: Les Maisons de la Région. These stores are situated in Shanghai, London, Casablanca and New York, providing among others commercial and logistic support to exporting enterprises in key markets. However, the name of these stores doesn’t follow the Sud de France logic, as their objectives go further than the scope of the brand; i.e. they also aim at attracting foreign investment, based on other assets such as logistics, tax reductions or research activities. Sud de France Development is financed by the regional government and supported by other public institutes, such as the regional Chamber of Commerce and Industry (CCI), the association of the agri-food industry LRIA (Languedoc-Roussillon Industries Agro-Alimentaires), or Invest Sud de France.11

Main private stakeholders are wine producers and farmers, food production companies and tourism service providers. As the agri-food sector of the region principally consists of small and very small producers and firms, cooperatives and inter-professional organisations constitute significant representatives. The big national retail groups such as Casino, Carrefour or Auchan also play an important role for the brand with their regular promotions for Sud de France products. Other interest groups are the inhabitants of the region and the national and worldwide consumers and tourists. Figure 4 illustrates the position and interrelations of the main stakeholders.

Brand effects

The effects of the Sud de France strategy have not yet been measured in detail. In order to capture the equity of the brand, we start with a presentation of mainly secondary data about the development and impact of the brand taken from different sources. Next, we concentrate on outcome patterns observed by key stakeholders in interviews.

In early stages, food enterprises were not enthusiastic about the brand, mainly because there had also been other failed collective brands before (Authentiquement Languedoc-Roussillon and Septimanie). Representatives from the government really needed to convince them to adhere, emphasising that Sud de France was not intended to be a substitute for their own brands, but an additional chance to create awareness and easier access to regional and international distribution channels. Some disagreement between various actors delayed an efficient implementation of the brand. However, the increasing total number of adherents (wine, food and tourism) in Table 3 demonstrates that the use of the brand has become attractive for local professionals.

A general study about the evolution of the regional agricultural sector (1997-2009) confirms the interest of food companies for the brand (De Caix et al. online document 2011). In 2009, the brand was used by 36% of the enterprises in the agri-food sector. In the wine sector, the percentage of adherents was 50%. From 2009 to 2012, the total number of adherents grew considerably. In 2013, the estimated percentage of participating food companies was about 90% (Interview C. Passat, 14 June 2013). Access to activities offered by Sud de France Development is given under the condition to become a brand member; companies took this for granted.

Another investigation in 2009 about the perception of Sud de France among 503 regional food enterprises produced the following statements, which demonstrated a major level of satisfaction (Agreste online document 2011):

– 80% of the companies declared that the brand contributes to increase the awareness of regional products on export markets;

– 72% of them considered that it helps to better sell their products;

– 68% believed that it contributes to create new markets.

Concerning the sales impact of the brand on the French large retail groups, results confirm that the promotional summer campaigns organised by Sud de France Development are profit-making.12 In 2010, the average sales increase of local food products labelled Sud de France within supermarkets has been 20% at regional level and even 30% at national level, compared to 2008 and 2009, when the increase was 5-10%.13

12 “Large retailers are not philanthropic. If they rep eat actions, it is because they profit from them”, analyses Chantal Passat. Cited from: www.lalettrem.fr (28 February 2012), translated by authors.

13 http: lalettrem.fr, 17 November 2009 and 18 January 2011.

In order to obtain figures from export, an economic analysis has been carried out for Sud de France wines in 11 countries from 2006 to 2011. The majority of destinations show a growth of sales volumes and profit, mainly in Asia and Brazil (Percq online document 2012). China is an exceptional leader, multiplying sales by 7 and profit by 8 times initial levels from 2006 to 2010. In this case, the region is the second to Bordeaux. From the beginning China was a main target country, a policy reinforced by the Maison Internationale in Shanghai including regular participation in important trade fairs. Furthermore, the analysis shows Sud de France wines to have a better resistance to global crises in the sector, and this is partially a result of the enormous quality improvements of Languedoc-Roussillon wines in general.14

There is not so much evidence from consumer side concerning Sud de France. In 2007, just one year after the brand launch, a study about the perception of the brand among regional inhabitants was carried out by TNS Sofres (online document 2007). At this time, only 43% of the respondents knew of the brand. About 63% had a positive attitude towards this regional project, while on average 20% which had a negative one. In 2013, the brand reached a high level of awareness at regional level (about 90%, according to the result of a confidential study done by a private consultancy), but it seemed that people could not define the content of the brand and didn’t know what it represents. However, from the perspective of wine experts, the benefits of Sud de France for consumers lies principally in the fact that it increases the awareness of provenance and facilitates the choice among a partly confusing multitude of references and quality signs in the French wine world.15

We performed thirteen interviews between November 2012 and June 2013, with persons from public institutions, representative organisations, various private companies and a tourism provider. The main objective was to investigate the perceived value added by Sud de France. A secondary question was whether the brand is helping to create a network of local actors.

Table of contents :

CHAPTER 1 An introduction to the dissertation

1.1. Introduction and problem statement

1.2. Societal context

1.2.1. The importance of place-based marketing in a global context

1.2.2. Regionalisation and decentralisation processes in Europe and Morocco

1.2.3. The Mediterranean area and its rich food heritage

1.3. Theoretical context

1.3.1. Place marketing and branding: origin, state-of-the-art in literature and critics

1.3.2. Regional studies

1.3.3. The sociology of local food, rural sociology and embeddedness

1.3.4. Conceptual diagram: linking marketing, regional studies and sociology

1.4. Objectives and research questions

1.5. Methodology

1.5.1. Choice of the research areas

1.5.2. Case study design

1.5.3. Data collection and analysis

1.6. Thesis outline

CHAPTER 2 How to capture place brand equity? The case of Sud de France

2.1. Introduction

2.2. Theoretical background

2.3. Methodology

2.4. Main results: the Sud de France case

2.4.1. Origin, objectives and strategy of the brand

2.4.2. Governance structure and stakeholders involved

2.4.3. Brand effects

2.5. Analysis of the case study and discussion

2.6. Conclusion

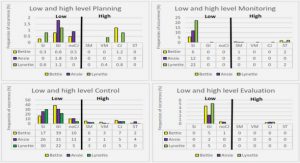

3 What kind of value for place brands? A stakeholder approach

3.1. Introduction

3.2. The value of brands

3.3. From identifying place brand stakeholders towards a monitoring tool

3.4. Methodology

3.5. Results

3.5.1. What kind of indicators for place brand value?

3.5.2. The value of place brands for residents and consumers

3.6. Discussion: monitoring place brand performances

3.7. Conclusion

CHAPTER 4 Place branding, embeddedness and rural development: Four cases from Europe

4.1. Introduction: valorising rural assets

4.2. Endogenous development and place branding

4.3. Place branding

4.4. Branding and embeddedness

4.5. Methodology

4.6. Four cases of regional branding from Europe

4.6.1. Produit en Bretagne (PeB)

4.6.2. A taste of West Cork (ToWC)

4.6.3. Sud de France (SdF)

4.6.4. Echt Schwarzwald (ES)

4.7. Comparison and analysis of the cases

4.8. Discussion and conclusions

CHAPTER 5 Co-creating territorial development and cross-sector synergy: A case study of place branding in Chefchaouen, Morocco

5.1. Introduction

5.2. Policy frameworks for development in France and Morocco

5.2.1. France

5.2.2. Morocco

5.3. Linking public policy to place branding

5.4. Methodology

5.4.1. Case study of territorial development

5.4.2. Data collection

5.4.3. Research location

5.5. Co-creation in Chefchaouen

5.5.1. The sequence of events leading to a place branding project in Chefchaouen

5.5.2. Examples of joint actions building a territorial image of Chefchaouen

5.6. Analysis of the case study

5.7. Discussion

5.8. Conclusion

CHAPTER 6 Results, discussion and conclusions

6.1. Introduction: the aim of the study

6.2. Main findings

6.3. Conceptualising and theorising collective place brands

6.3.1. The collective place branding concept

6.3.2. Conditions, dynamics and processes of collective place branding

6.3.3. Assessing territorial development outcomes of collective place brands

6.4. Methodological implication: case study approach to collective place brands

6.5. Practical implications for development policies and place brand management

6.6. Suggestions for further research

6.7. Conclusion

References

Summary