Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Agglomeration Effects in a Developing Economy: Evidence from Turkey

Urbanization has shaped developed countries during the 20th century, but it has had transformative effects on developing countries. Several major factors distinguish urbanization in developing countries from urbanization in developed countries. First, urbanization in developing countries is occurring at a quicker pace. In the last 50 years, on the back of a strong wave of rural-urban migration, emerging countries have seen the number of large cities increase. It took more than a century for most developed countries from the time urbanization started to increase markedly until they reached 50%. Today’s developing countries often reach that threshold in less than half the time. Second, much larger numbers are involved making it a relevant issue for large numbers of people.

Given the importance of the topic, the third chapter of this dissertation focuses on understanding the determinants of regional productivity in a developing country context. For such a study, Turkey, an upper-middle-income developing country that has experienced fast urbanization and a high rate of growth of the urban population, seemed like a natural fit. Since the 1950s, the urban population in Turkey has increased dramatically due to massive rural-to-urban migration and a high fertility rate. In 1960, Turkey still featured a largely agrarian economy with 31 percent of its population residing in urban areas. By 2017, 75% of the Turkish population lived in cities, making it a very highly urbanized country. Today there are substantial inequalities between regions on almost every metric (income, production, life quality, etc.), including productivity.

In this study, I focus on understanding the sources of spatial productivity differences. For this purpose, I use social security records, a new administrative dataset that has only recently become available to researchers and thus has never been used in research before. Combining these records with various other datasets, I apply the standard two-step estimation approach to analyze the relationship between agglomeration economies and productivity in Turkey. Specifically, I attempt to measure the elasticity between employment density and productivity gains associated with denser urban areas. I address the endogeneity bias due to reverse causality by using historical instruments based on census data from the Ottoman Empire and the early years of the Turkish Republic.

My results show that agglomeration economies are powerful and at levels that are expected given Turkey’s urbanization level. The elasticity fits the literature perfectly and contributes to filling the knowledge gap about urbanization dynamics in the developing world. Beyond finding strong gains associated with denser agglomerations and market access, I also find that workers do not sort across locations based on their observable skills. This result is in sharp contrast with what is usually observed for developed countries, where a large fraction of the explanatory power of cities productivity advantages arises from sorting of the workers with higher abilities to denser and larger cities. Overall my findings corroborate earlier findings for developing countries, which show that while the main mechanisms of urban economies are present in the developing world, the current models need to be extended to capture the differences between Western cities and those in the developing world.

Concluding Remarks

Overall, the articles that constitute this dissertation aim to explore the interaction between migration and productivity, through multiple angles, across three different country and period contexts. Specifically, I study the labor market benefits of migrant mobility during an economic crisis, productivity gains due to migrant mobility in the reconstruction of a country in the aftermath of a war, and gains associated to the concentration of people coming from different parts of the economy, to generate higher growth and income. All of the chapters of this dissertation aim to understand the effects that arise from human mobility, across cities and countries. The findings of these studies relate to many issues that interest both the academia and the policymakers yet on which little is known. This dissertation aims to contribute to knowledge gap on issues that will remain relevant foreseeable future.

Introduction Generale

Qu’on les observe à l’âge reculé des chasseurs-cueilleurs, ou au sein de nos économies contemporaines, les migrations et la répartition spatiale de la productivité sont des phénomènes structurant de nos sociétés qui demeurent interconnectés. En un sens les migrations sont affectées par la répartition spatiale de la productivité. Si les hommes se déplacent c’est, dans bien des cas, 1) en quête d’opportunités apportées par la croissance économique, 2) dans l’espoir d’améliorer leur pouvoir d’achat ou 3) d’accumuler des richesses. Ces trois types de motivations dépendant fortement de la productivité, la répartition spatiale de la productivité joue un rôle significatif sur l’orientation des flux migratoires. Mais dans un autre sens, la répartition de la productivité est affectée par les migrations, car elle dépend non seulement des caractéristiques de l’individu, mais également du pays ou de la région dans laquelle il exerce son travail. Dès lors les flux migratoires doivent évoluer au grès des changements de productivité.

Durant la révolution industrielle, alors que les pays occidentaux surmontent les inerties caractéris-tiques des régimes de croissance pré-moderne, le reste du monde continue d’arborer des taux de croissance faible. S’opère alors une « Grande Divergence » (Pommeranz, 2000) des niveaux de productivité (et donc de revenus) entre les États occidentaux et le reste du monde qui, en s’accélérant, s’accompagne de l’émergence d’inégalités territoriales au sein même des pays. De telles différentiels spatiaux engendrent alors mécaniquement des mouvements de population tant entre États qu’en leur sein même. Il n’est donc pas surprenant que les migrations demeurent aujourd’hui un enjeu de taille. Ces dernières années, l’augmentation des flux migratoires dans le monde, ainsi que l’afflux de réfugiés à travers l’Europe, les placent au cœur des débats politiques qu’intellectuels.

A l’instar des phénomènes migratoires, les déterminants de la productivité font l’objet d’un intérêt accru depuis quelques années tant dans les milieux politiques qu’universitaires. Le ralentissement de la croissance depuis le milieu des années 2000, accentué au lendemain de la Grande Récession, est une cause évidente de ce regain d’intérêt. Améliorer le pouvoir d’achat par le truchement d’une croissance durable et inclusive constitue un incontournable de l’agenda politique des gouvernements du monde entier. Or la croissance de la productivité est une condition d’autant plus nécessaire à l’avènement d’une telle croissance, que le vieillissement démographique en menace la pérennité.

Ce regain d’intérêt s’impose également chez les universitaires, pour des raisons méthodologiques. L’usage des données migratoires apparaît comme de plus en plus à même de nous faire entrer dans cette « boite noire » qu’est la productivité et, partant, d’identifier les canaux par lesquels elle peut être stimulée. Par conséquent, cette thèse est composée d’études qui se concentrent sur l’interaction entre phénomènes migratoires et la productivité, sous angles différents, en des espaces géographiques et des périodes divers.

Table of contents :

1 General Introduction

1.1 Cushioning Effect of Immigrant Mobility: Evidence from the Great Recession

1.2 Migration and Post-conflict Reconstruction: The Effect of Returning Refugees on Export Performance in the Former Yugoslavia

1.3 Agglomeration Effects in a Developing Economy: Evidence from Turkey

1.4 Concluding Remarks

2 Introduction Generale

2.1 Effet Amortisseur de la Mobilité des Immigrants

2.2 Migration et Reconstruction Post-conflit : L’Effet du Retour des Réfugiés sur les Exportations en ex-Yougoslavie

2.3 Economies d’Agglomération dans un Economie en Développement : Le Cas de la Turquie

3 The Cushioning Effect of Immigrant Mobility: Evidence from the Great Recession in Spain

3.1 Introduction

3.2 An Equilibrium Model with Heterogeneous Labor Supply, Demand Shock and Wage Rigidities

3.2.1 Set-up

3.2.2 Equilibrium Effect of Migration and Demand

3.3 Spanish Context

3.3.1 The Great Recession

3.3.2 Immigrant Population in Spain

3.3.3 Immigrant vs. Native Mobility

3.4 Data and Summary Statistics

3.4.1 Data

3.4.2 Summary Statistics

3.5 Empirical Strategy

3.5.1 Econometric Equation

3.5.2 Identification

3.6 Main Results

3.6.1 First Stage and Validity of Instruments

3.6.2 Second Stage

3.7 Robustness

3.7.1 Previous-trends

3.7.2 Bartik and Other Controls

3.7.3 Alternative Instruments

3.7.4 Alternative Measures of the Supply Shock

3.7.5 Alternative Weights

3.8 Dynamics of Adjustment

3.9 Heterogeneity Analysis

3.9.1 By Skill Group

3.9.2 By Demographics

3.9.3 EU versus non-EU outflows

3.10 Mechanism

3.10.1 Geographic Mobility of Natives

3.10.2 Margins of the Employment Effects

3.10.3 Margins of the Wage Effects

3.10.4 Margins by Contract Types

3.11 Understanding the Magnitude of the Estimates

3.12 Concluding Remarks

3.13 Appendix

3.13.1 Derivation of the Firm’s Demand Curve

3.13.2 Derivation of Labor Supply

3.13.3 Derivation of Equilibrium Wage and Employment Responses under Flexible Wages

3.13.4 Firms Adjustment During the Crisis

3.13.5 Differences in Unemployment Rates

3.13.6 Reconciling with Cadena and Kovak (2016)

3.13.7 Immigrant Population

3.13.8 Government Measures

3.13.9 Net Immigrant Departures as a Share of Total Working-age Immigrant Population

3.13.10More on Mobility Data

3.13.11Construction of the instrument

3.13.12 Instrument Validity

3.13.13Construction of Bartik control

3.13.14Immigrant and Native Outflows

3.13.15Maps

3.13.16Differentiating Between Boom and Bust

3.13.17Part-time Employment

4 Migration and Post-conflict Reconstruction: The Effect of Eeturning Refugees on Export Performance in the Former Yugoslavia

4.1 Introduction

4.2 Historical Context

4.3 Labor Market Conditions and Mobility of Refugees

4.4 End of the War and Deportation

4.5 Data and Sample

4.6 Natural Experiment: Yugoslavian Refugees

4.6.1 Empirical Strategy

4.6.2 Summary Statistics

4.7 Results

4.7.1 Pre-trend and Event-study Estimation

4.7.2 Robustness and Heterogenous Effects

4.8 Mechanisms: Heterogeneous Effects by Workers’ Characteristics

4.9 Concluding Remarks

4.10 Appendix

4.10.1 Anecdotal Evidence: Four Individual Stories

4.10.2 Details on Employment Data, Sample Construction and Variable Description

4.10.3 Zeroes in the Data

4.10.4 Including Exports to Germany

4.10.5 Additional Controls

4.10.6 Further Tests on the Exogeneity of Exit From the Labor Force

4.10.7 Robustness: German WZ 93 3-digit Industries

4.10.8 Other Robustness Checks

4.10.9 Excluding Slovenia and Macedonia from the Sample

4.10.10Occupations by Characteristics

4.10.11Estimations Using Treatments by Educational Attainment and Occupations Characteristics

4.10.12Expanding to All Countries: External Validation

5 Agglomeration Effects in a Developing Economy: Evidence from Turkey

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Literature Review

5.2.1 Agglomeration Economies

5.2.2 Magnitudes for the Effect of Density on Workers’ Productivity

5.2.3 Evidence from Developing Countries

5.3 The Turkish Context

5.4 Literature on Regional Differences

5.5 Data and Sample

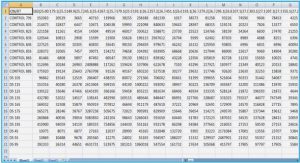

5.5.1 Social Security Data

5.5.2 Household Labor Force Survey

5.5.3 Historical Data

5.5.4 Controls

5.5.5 Sample

5.6 Empirical Strategy

5.6.1 Econometric Equation

5.6.2 Estimation Issues

5.6.3 Estimation Issue 1: Omitted Variables

5.6.4 Estimation Issue 2: Circular Causality

5.6.5 Estimation Issue 3: Accounting for Local Shocks

5.6.6 Estimation Issue 4: Sorting by Ability

5.7 Main Results

5.7.1 Density

5.7.2 Omitted Variable Bias

5.7.3 Reverse Causality

5.7.4 Sorting By Ability

5.8 Multivariate Approach: A Unified Framework

5.9 Infrastructure and Other Amenities

5.10 Concluding Remarks

5.11 Appendix

5.11.1 Summary Statistics

5.11.2 Yearly OLS results

5.11.3 One-step results

5.11.4 Individual Analysis

5.11.5 Informal Employment

5.11.6 First Stage of Multivariate Regression

5.11.7 Additional Results: Infrastructure and Amenities