Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Have financial reforms improved financial systems’ size and liquidity in developing countries?

Introduction

The existing literature on the finance-growth relationship emphasizes that financial development matters for economic growth by alleviating market frictions induced by transaction and information costs (see for instance McKinnon, 1973, Shaw, 1973, King and Levine, 1993a, Levine, 1997). By attenuating these market frictions, financial systems fulfill the primary function of paving the road to an efficient resource allocation across space and time in uncertain environments.

Levine (1997) breaks this primary function into five basic components, namely, savings mobilization (1), capital allocation (2), corporate governance and management monitoring (3), trading, hedging, and diversification and pooling of risks (4), and promotion of exchange of goods and services (5). Financial development therefore occurs when the financial system is more efficient in providing its five functions (Levine, 2004). Similarly, Huang (2006) defines financial development as the capacity of a financial system to enhance the efficiency of financial resources’ allocation and to monitor capital projects through improved competition and financial depth. Financial development is hence a matter of structure, size, and efficiency of a financial system.

It is commonly asserted that financial development may be fostered by financial reforms and through several mechanisms. First, reforms may alleviate financial repression in protected financial markets, thereby allowing real interest rates to reach their competitive market equilibrium level. Second, the removal of capital controls allows domestic and foreign investors to hold more diversified portfolios, which in turn may decrease the cost of capital. Third, financial liberalization leads to more integrated markets, which also helps reducing the cost of capital. Fourth, reforms of the financial infrastructure may lessen information asymmetry, thus reduce adverse selection and moral hazard effects, and increase funds availability. Last, but not least, the liberalization process often contributes to improving the financial system’s efficiency by removing inefficient financial institutions (Ito, 2005).

In an effort to spur the development of their financial systems, a great number of developing countries implemented structural reforms of their financial sectors in the 1980s and the 1990s. Although their extent and pace vary across regions, these reforms often include the opening of financial markets, thus giving foreign investors the opportunity to invest in domestic equity securities and increasing domestic and foreign competition, the lessening of public interferences, and the removal of restrictions on financial activities, in particular, through the removal of interest rates and credit controls, the privatization of commercial banks coupled with the strengthening of the independence of central banks, and the introduction of financial regulation and supervision.1

However, the financial crisis episodes in Asia (1997), Mexico (1994), and Russia (1998), as well as the more recent global financial crisis of 2007-2008, have raised a new debate on the costs and benefits of financial liberalization. Some economists have warned on the need for developing countries to put some limits on capital inflows to alleviate excessive shifts in financial markets (Stiglitz, 2000, Bekaert et al., 2005, Kaminsky and Schmukler, 2002). Some authors have even argued that the effects of these crises were amplified by financial liberalization (Ang and McKibbin, 2007, Tswamuno et al., 2007).

Despite the potential adverse effects of capital account liberalization, policy makers do not seem to have given up the path of financial reforms. In the contrary, they pay a great attention to the link between economic development and financial integration, focusing on the importance of financial liberalization sequencing and its effects on financial development, economic growth and stability, and on the importance of the institutional environment, in particular, better supervision and regulation of the financial sector.

Most empirical studies of the finance-growth relationship have reported a positive impact of financial development on economic growth (Levine, 1997, Beck and Levine, 2002, Spiegel, 2001, Abdurohman, 2003). However, the studies of the effects of financial reforms on financial development have essentially focused on the impact of capital account opening on the level of development of the banking sector, hence leaving out stock markets and other important aspects of the reforms.2 This chapter attempts to contribute to filling this void by incorporating a larger set of reform measures that have been implemented and by distinguishing the banking sub-sector and the capital markets in the investigation of the effects of financial reforms on the development 1 In many developing countries, the banking sub-sector represents the largest share of the financial sector. Consequently, one should expect the implemented reforms to have a more perceptible effect on this sub-sector than on the yet emerging securities markets. of emerging and developing countries’ financial sector.

Fixed-country effects regression models are fitted to a 1973-2005 annual dataset on 54 emerging and developing countries. Financial development indices are constructed from variables that capture the size and the degree of liquidity of the banking sector and stock markets. Moreover, reforms indicators considered in our empirical analysis seize various dimensions of the implemented policies, in particular, the degree of openness of the financial sector to domestic and international financial institutions and investors, the degree of competition introduced in the sector, the level of privatization, and the extent of regulation. In line with the existing literature, the level of country risk and factors describing the institutional environment are also accounted for.

Our analysis of the overall effects of the reforms undertaken by emerging and developing countries on these countries’ financial sector shows that, although a two-year adjustment period has been sometimes required, the reforms have significantly improved the development of the financial systems. When examining separately the effects of banking and securities markets reforms, we find that they have effectively spurred the development of respectively the banking sector and stock markets as early as the year of their implementation. Interestingly, our findings also highlight that country risk and the quality of institutions are factors that affect significantly financial development, and hence have a role to pay in the reforms effectiveness. We also find evidence that economic development and trade liberalization contribute to financial deepening while political regime change does not seem to be beneficial.

This chapter is organized as follows. The next section provides a review of the literature that discusses the importance of financial reforms for the development of the financial sector and economic growth. Section 3 describes the data used and briefly discusses the main properties of the variables of interest. Section 4 presents the econometric analysis and the results obtained. Section 5 concludes and Appendix 1 gives further details on the data and some summary statistics.

Related literature

The actual relationship between financial reforms, financial development and economic growth is of great importance to developing and emerging countries’ policymakers. Indeed, convincing evidence that the financial system’s development has positive effects on long-term growth will induce further research on the political, legal, regulatory and policy determinants of financial development and influence the priority attached to reforming the financial sector. Moreover, it would allow countries to stimulate their economic development by exploiting benefits from financial reforms (Levine, 2004). Levine (2001) examines whether international financial liberalization can foster economic growth by enhancing the functioning of domestic financial markets and banks. Focusing on the long-term effects of international financial integration, he finds that the latter can positively affect economic growth through mechanisms not often highlighted by the existing literature. First, the presence of foreign banks tends to boost the domestic banking system’s efficiency, thereby stimulating productivity and growth. Second, lifting restrictions on international portfolio flows spurs the domestic stock market’s liquidity, which also fosters productivity and growth.

Ang and McKibbin (2007) study the finance-growth relationship in Malaysia through cointegration and various causality tests, using time series data from 1960 to 2001, and accounting for saving, investment, trade and real interest rate. Unlike Levine (2001), their empirical results show that even if financial liberalization has enlarged the financial system, it has not resulted in higher long-run growth. On the contrary, output growth appears to have a positive causal effect on financial depth in the long-run.

Similarly, Tswamuno et al. (2007) analyze the effects of financial liberalization in South Africa using data from 1975Q3 to 2005Q1 and find that increased stock market liquidity and non-resident participation after liberalization did not foster economic growth. Moreover, increased integration has had a negative effect on economic growth. These findings suggest that financial liberalization may have adverse effects on economic growth if no appropriate foundations are set to stabilize the real economy.

The existing literature focusing on the effects of financial reforms on financial development, which is the subject of this study, has led to results varying across countries and methodologies. Claessens et al. (1998) investigate the effects of capital account opening on the domestic banking system using bank-level data on 80 countries covering the period 1988-1995. They find that opening banking markets and the increase in the number of foreign entrants, rather than their market share, enhance domestic banking systems’ efficiency with reduced profitability and expenses in domestically owned banks.

Huang (2006) studies the relationship between financial openness and financial depth in 35 emerging markets from 1976 to 2003, with measures of financial openness and financial development comprising variables from the banking sector, stock markets and national capital accounts. His findings indicate that financial openness is a key determinant of the level of financial development. When testing this effect on the development of the banking sector and that of stock markets separately, a strong and robust link is found for stock markets only. For the case of Chile, De Gregorio (1999) also finds that higher financial integration leads to a deeper financial sector.

Likewise, Klein and Olivei (1999) analyze the effects of capital account opening on both financial depth and economic growth for developed and developing countries from 1976 to 1995 and from 1986 to 1995 respectively. Their results from cross-section analysis show that countries that opened their capital accounts exhibit significantly greater increase in financial depth than countries that maintained capital account restrictions and these findings hold in particular for developed countries. In contrast, capital account liberalization failed to foster financial depth in developing countries, suggesting that economic, legal, and institutional reforms are needed in these countries for capital account liberalization to stimulate financial development.

Some authors indeed paid a particular attention to the importance of accounting for the level of legal and institutional development when investigating the impacts of financial reforms on financial development. Ito (2005) examines whether financial openness led to financial systems’ deepening in Asia from 1980 to 2000, while controlling for countries’ legal and institutional development. His findings show evidence that a greater level of financial openness fosters equity market development only if a certain level of legal development has been reached.

Similarly, Chinn and Ito (2006) emphasize that a threshold of legal and institutional development has to be achieved for financial liberalization to contribute to equity markets’ development, in particular in emerging market countries. More precisely, a higher level of bureaucratic quality and law and order as well as low corruption may significantly improve the effect of financial liberalization in boosting equity markets’ development.

Using an error-correction panel model with non-overlapping data for ten South Mediterranean Sea (SMS) countries from 1980 to 2005, Beji (2007) also tests the impact of legal and institutional development on the effects of financial liberalization on financial development. The author reaches the same conclusion as Chinn and Ito (2006), that is to say that countries should first improve their legal and institutional environment to benefit from the positive effects of financial liberalization.

Tressel and Detragiache (2008) study the effects of banking sector reforms on the level of development of the financial sector of 85 countries over 1973-2005 using a newly available database on implemented reforms. They find that financial reforms indeed improve the banking sector’s development but only in countries with well-developed political institutions. For the case of Mediterranean countries from 1985 to 2009, Ayadi et al. (2013) find that strong legal institutions, good democratic governance, and the proper implementation of financial reforms may have a significant positive effect on financial development, provided that they are jointly present.

This chapter seeks to contribute to the existing literature by empirically examining how the various dimensions of financial reforms affect the sector’s level of development, considering both the banking sector and stock markets, and accounting for country risk and institutional environment.

The data

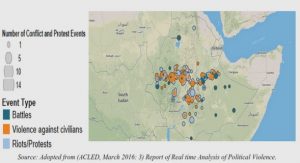

To investigate the effects of financial reforms on the financial sector’s development, we collected data on 54 emerging and developing countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), Asia, Middle East and North Africa (MENA), and Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) as shown in Table 1.1 below. This table also gives the World Bank income group each of these countries belongs to. 3 The study covers the period from 1973 to 2005 as dictated by data availability but also to include pre and post reforms periods. Moreover, not all the data were available for all the years and countries, leading to an unbalanced panel and a number of observations varying across models.

Table 1.2 exhibits the list of variables on which data have been collected.4 The financial development index findev, the main dependent variable in this study, seizes the level of development of countries’ overall financial sector and is calculated as the first principal component of variables that represent the development of the banking sector and stock markets. The depth of the banking sector is captured by the variable of domestic banks liquid assets as a fraction of GDP denoted bsdev. For stock markets we use the variables smc and tvt which are also expressed as ratios to GDP and represent, respectively, stock market capitalization and the value of shares traded. These variables are meant to measure the size of the capital market and its liquidity respectively and we denote smdev their first principal component.

The main independent variables of interest are grouped under the label « Financial reforms ». Overall financial reforms are measured by the global index finreforms from Abiad et al. (2008). This index seizes seven features of financial reforms, namely credit controls and reserves requirement, interest rate control, entry barriers into the banking sector (competition), the extent of privatization of domestic banks, the banking sector’s supervision (regulation), capital account liberalization, and policies undertaken to restrict or stimulate the development of bond and stock markets. The latter dimension of reforms comprises measures such as the possibility of auctioning government securities, the establishment of debt and equity markets, and the implementation of measures to encourage the development of these markets such as tax incentives or the development of depository and settlement systems, and policies promoting (or restricting) the openness of securities markets to foreign investors.

We denote bsreforms the banking sector reforms index calculated as the sum of policies targeting the banking sector while smreforms refers to implemented policies affecting stock markets. The higher these variables’ score, the less repressed the financial sector. For robustness checks, we also consider another indicator of reforms that is not based on a scoring system, namely controls on private capital flows (privcap) into a given country. Expressed as a ratio of GDP, this variable captures the extent of financial liberalization and is equal to the sum of net foreign direct investment, net portfolio investment and other investments in the balance of payments. The main conjecture of this chapter is that implemented financial reforms as measured by variables finreforms, bsreforms, smreforms, and privcap are key determinants of the development of sample countries’ financial sector.

Table of contents :

General introduction

Chapter 1 Have financial reforms improved financial systems’ size and liquidity in developing countries?

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Related literature

1.3 The data

1.4 Empirical analysis

1.4.1 Overall effect of financial reforms on the level of development of the financial sector

1.4.2 Disentangling the effects of the banking sector and securities markets reforms

1.5 Conclusion

Chapter 2 The relationship between financial development and private investment in the power sector

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Background and review of some related work

2.3 The Data

2.4 Empirical analysis

2.5 Conclusion

Chapter 3 To what extent do infrastructure and financial sectors reforms interplay? – Evidence from panel data on the power sector in developing countries

3.1 Introduction

3.2 The performance of the power sector reforms

3.3 The role of the financial sector reforms: Some testable hypotheses

3.4 The data

3.5 Empirical analysis

3.6 Conclusion

References

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3