Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

SCARCE SKILLS CAREER PATH: ENGINEERING PROFESSIONAL SKILLS

According to Powell and Groenmeyer-Edigheji (2006:4), it is expedient to elucidate the meaning of economic terms, such as scarce skills from the onset of any discussion in order to order ambivalence. They argue that different understanding of such terms is likely to cloud remedial decision making, leading to different remedial decisions. In this study, scarce skills can be regarded as those that are generally in short supply within the labour market. Immense emphasis is placed on professional engineering skills as high-level skills. Technical and artisan skills are excluded. For the purpose of this study, professional engineering skills are regarded as post-school career paths for the mathematics and science learners. The etymology of the word engineer can be traced back to more than 2000 years. It is derived from the Latin word ‗ingenium‘ meaning skill (Potter 2011:15). Engineering is defined as the science of applying knowledge, tact, craft or ingenuity to solve practical problems of industry (e.g. the construction of industrial plants or machines). Roodt and du Toit (2009:75) identify three main types of engineering professionals in South Africa, namely, engineers, engineering technologists and engineering technicians. Roodt and du Toit (2009) further point out that the designation depends on the tertiary qualifications that are attained. Engineers hold a four-year Bachelor of Science in Engineering (BSc (Eng)) or Bachelor of Engineering (BEng/BIng) degree from a university; technologists hold a national diploma (NDip) from a university of technology. Throughout this study, Mathematics and Science education are regarded as the conduits for the attainment of a career in engineering. Engineering is regarded as one of the scarce career paths in the South African labour market.

THE NATURE OF EDUCATIONAL POLICY

According to Anderson (1994:5-6; cf. Also Anderson 2006:6) policy involves a purposive course of action formulated by the authorities in the political system to deal with a problem or matter of concern. Purposive implies that policy is neither a random decision nor an opportunistic occurrence. Rather, policy is a goal-inclined action that comes out of a response to a particular problem or demand. In the same manner and as it is the case with a myriad of public policies, education policy is equally goal-inclined. Hartshorne (1999:5; cf. Waghid 2002:1-2) concurs with Anderson‘s definition of policy and augments it by giving a comprehensive definition of education policy as ‗a course of action adopted by government through legislation, ordinances and regulations, and pursued through administration and control, finance and inspection, with the general assumption that it should be beneficial to the country and its citizens‘. Education policy therefore entails a legalised course of action driven by specific purposes. Drawing from Hartshorne‘s (1999) definition, education policy is imbued with authority; hence it has the power to achieve the intended goals. In line with this perspective, Adams (2004:36; cf. Also Ball 2006:43-50) points out that education policy has the power to structure and to guide government actions.

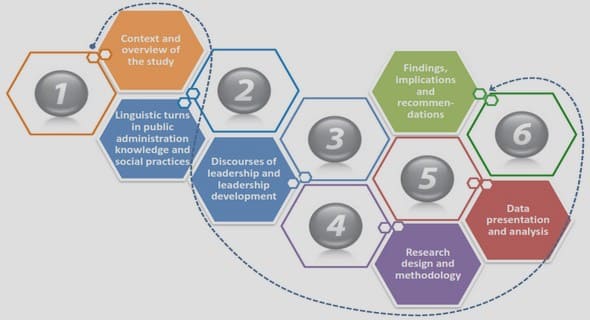

CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND TO THE SCARCE SKILLS CHALLENGE IN SOUTH AFRICA

1.1 INTRODUCTION

1.2 MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY

1.3 THE OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY

1.4 SCARE SKILLS CAREER PATH: ENGINEERING PROFFESSIONAL SKILLS

1.5 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF EDUCATION AND TRAINING IN SOUTH AFRICA-A GENERIC OVERVIEW

1.6 SCHOOL EDUCATION ACHIEVEMENTS IN THE POST APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA

1.7. THE POST-APARTHEID FORMAL EDUCATION STRUCTURE IN SOUTH AFRICA

1.8 SOME WEAKNESSES IN THE POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICAN SCHOOL EDUCATION SYSTEM

1.9 THE CHALLENGES OF SCARCE SKILLS

1.10 THE NATIONAL STRATEGY FOR MATHEMATICS, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY EDUCATION (NSMSTE)

1.11 THE NATURE OF EDUCATIONAL POLICY

1.12 LIMITATIONS TO THE SCOPE OF THE STUDY

1.13 THE DIVISION OF CHAPTERS

1.14 CONCLUSION

CHAPTER 2: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

2.1 INTRODUCTION

2.2 QUALITATIVE RESEARCH DEFINED

2.3 QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH DEFINED

2.4 RESEARCH METHODS CHOSEN FOR THIS STUDY

2.5 DATA COLLECTION, GARNERING OF INFORMATION AND ANALYSIS

2.6 PROBLEM STATEMENT

2.7 RESEARCH DESIGN

2.8 SAMPLING METHOD AND SAMPLING SIZE

2.9 RESEARCH QUESTION

2.10 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

2.11 RESEARCH SCOPE

2.12 CONCLUSION

CHAPTER 3: REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE ON THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION AND POLICY IMPLEMENTATION

3.1 INTRODUCTION

3.2 PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION

3.3 DEFINITION OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION

3.4 POLITICS AND ADMINISTRATION

3.5 POLICY AND POLITICS

3.6 STRUCTURAL ADMINISTRATION

3.7 ADMINISTRATIVE SYSTEMS

3.8 DEFINITION OF POLICY IMPLEMENTATION

3.9 POLICY IMPLEMENTATION AS A CORE FUNCTION OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION

3.10 CRITICAL VARIABLES FOR THEIMPLIMENTATION OF POLICY

3.11 POLICY IMPLEMENTATION WITH RESPECT TO SKILLS DEVELOPMENT

3.12 POLICY EVALUATION

3.13 MODELS OF COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION IN EDUCATION

3.14 SCARCE SKILLS DEFINED

3.15 ADMINISTRATION MODELS OF THE PROGRAMMES TO DEVELOPSCARCE SKILLS IN THE PUBLIC EDUCATION SYSTEM OF OTHER COUNTRIES

3.16 CONCLUSION

CHAPTER 4: OVERVIEW OF THE RELEVANT LE GAL FRAMEWORKS FOR THE ADMINISTRATION IN SOUTH AFRICA

4.1 INTRODUCTION

4.2 EDUCATION AND THE LAW

4.3 LEGISLATION APPLICABLE TO PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION

4.4 SOME OF THE KEY EDUCATION POLICIES IN SOUTH AFRICA SINCE 1994

4.5 THE CONSTITUTIONAL BASIS FOR THE ADMINISTRATION OF EDUCATION SOUTH AFRICA

4.6 THE BILL OF RIGHTS

4.7 PUBLIC STATUTORY SUPPORT OF EDUCATION IN SOUTH AFRICA

4.8 NATIONAL AND PROVINCIAL STRUCTURES DEVOTED TO THE ADMINISTRATION OF BASIC EDUCATION IN SOUTH AFRICA

4.9 CONCLUSION

CHAPTER 5: ANALYSIS OF CASE PAGE

5.1 INTRODUCTION

5.2 HUMAN CAPACITY

5.3 SCHOOL MANAGEMENT

5.4 DISTRICT SUPPORT

5.5 ANALYSING THE REASONS FOR THE LOW PRODUCTIVITY OF OUTCOMES IN SCHOOLS

5.6 ANALYSIS OF THE DATA GATHERED FROM THE QUESTIONNAIRES

5.7 CONCLUSION

CHAPTER 6: FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

6.1 INTRODUCTION

6.2 SYNOPSIS OF THE CHAPTERS

6.3 CONCLUSION