Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Chapter 3 Research approach and methodology

If you are going to pose yourself a problem and then come to the conclusion about it, you have to do something to come to the conclusion. That ‘something’ is your method (Hofstee 2011)

Introduction

In research, the fundamental characteristic of the scientific method is empiricism – knowledge that is based on observations (Cozby 2005). Therefore, the data that form the basis about the conclusions on gender and cassava value chains are systematically collected governed by a number of rules that are explained in this chapter. The study problematised gender inequality in cassava food value chains at household level and made a gendered analysis focusing on gender roles, women empowerment and participation in the cassava value chain as influenced by certain household gender dynamics. As highlighted in section 1.4, the intention of this study is to enable women to escape poverty and food insecurity through improved resource ownership, decision making, market participation and control of income in the cassava value chain. This can be achieved through a thorough review of the socio-political and economic policy framework as well as an in-depth investigation of how individuals within households control resources, participate in various cassava value chain nodes, allocate time, bargain and control income. The focus of this study was therefore, framed into one major objective and four specific objectives, which guided the research approach and methodology adopted and presented in this chapter.

The research approach adopted in this study disentangled cassava value chain nodes to investigate the gender inequality at each value chain node at the household level. The approach uses literature and key informant interview information at the national and community levels linking them to their implications on individual households involved within the cassava value chains. The study therefore, adopted a mixed-methods approach, incorporating both qualitative and quantitative designs to gather data at different levels in Tanzania. The chapter thus, describes and explains the research design, sampling, data collection methods and data analysis techniques used in this study. The study was divided into the macro level and micro level of research. The macro level in this context focused more on gender and agriculture policy issues in Tanzania whilst the micro level focused entirely on individual household cassava farming activities as influenced gendered power dynamics within the households.

Research design and sampling

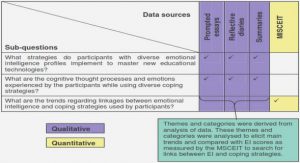

The research design adopted in this study is descriptive study. This is because it involved the examination of three case study sites together with the naturalistic observation as well as a household based survey. A mixed-methods approach was employed where both quantitative and qualitative data were collected using a range of research techniques. Thus, the research design involved the collection, analysis and integration of qualitative and quantitative data (Guetterman et al. 2017). The primary purpose of mixed methods was to integrate both qualitative and quantitative data to generate meta-inferences (Figure 3.1) beyond what either each approach could have achieved alone or produce well validated conclusions. Mixed methods also allowed for the exploration of a range of confirmatory (verifying knowledge) and exploratory (generatingknowledge) research questions concurrently within the same study phase (Teddlie & Tashakkori 2009). In this particular study, the convergent mixed-methods design was adopted which consists of aquantitative strand and qualitative strand being conducted independently of each other and the integration of the two strands mostly occurred at the interpretation stage when the results of the two approaches were brought together (Guetterman et al. 2017).

This approach was adopted in this study, where quantitative data from the household survey was supported by qualitative data from desk review, key informant interviews and focus group discussions. The mixed-methods approach used the concurrent time order dimension in which both the qualitative and the quantitative strands are conducted at approximately the same time (Christensen, Johnson, & Turner 2015). The quantitative dominant status was the paradigm emphasis adopted whereby the quantitative data was mainly used to address most research questions and hypotheses and then supported by the qualitative data where applicable. Qualitative research focuses on people behaving in a natural setting and describing their own world in their own words while quantitative research tends to focus on specific behaviours and attributes that can easily be quantified (Cozby 2005). Qualitative research is also more focused on individual people, local groups for intensive case studies; therefore there is little interest in obtaining results that are broadly generalisable.

A mixed methods approach has been used in the pigeon pea value chain studies in which gender relations and the implications for income and food security in Malawi were determined (Me-Nsope & Larkins 2016). In the process, the following methods were used:

focus group discussions,

key informant interviews and;

structured interviews.

Andersson et al. (2016) also employed a mixed-methods approach in a study on implications of gender on a cassava leaves value chain in the Mkuranga district of Tanzania. This method was also adopted in the dairy value chain project in Bangladesh and also in the gendered analysis of dairy production and food security in Mozambique (Rubin 2016). In addition, mixed methods were employed in a study on intra-household analysis of gender differences in climate change adaptation strategies and participation in group-based approaches in rural Kenya (Ngigi, Mueller & Birner 2017).

Similarly, Dito (2011) used a mixed-methods approach in a study on intra-household bargaining and resource allocation in developing countries, where the study involved the use of household based survey and focus group discussions as a qualitative strand. For the purposes of this study, the macro and meso levels were combined and considered as one level. The macro level entails the consideration of national domestic economy, policies and national systems whilst the meso level considers the gender laws, norms, rules, systems and gender differentiated entitlements and access (Kanji & Barrientos 2002), as they affect the cassava value chain. The micro level considers gendered division roles of production, reproduction and power dynamics within households along the cassava value chain. These two levels were considered as argued by Kanji and Barrientos (2002) that gender analysts emphasise that the strategic behaviour and individuals within households must be linked to wider social processes, institutions and power structures to have a comprehensive gender analysis of food value chains.

Hence in a gendered value chain analysis, there is need to link the macro and micro levels through the meso level institutions which include public service (infrastructure) and markets taking cognisance of the guiding gender norms, rules, custom systems and entitlements. At the macro level, purposive sampling was used to identify key informants for specific themes of interest. A multi-stage sampling procedure was employed at the micro level where major cassava producing regions and districts were purposively sampled, and cluster sampling was then used to select cassava producing villages within the selected districts. Simple random sampling was finally employed to select the individual household heads that were interviewed. This approach managed to generate enough qualitative and quantitative data that were useful in addressing questions on gender roles, actors involved, women empowerment and women participation in various cassava value chain nodes.

Macro-level research

The study began with the analysis of food security agricultural development policy and gender policy in Tanzania. As part of macro-level research, data were also gathered directly from key informants. This level of the study focused on agriculture and gender policy analysis at national level, which also includes the analysis of the socio-political and economic context under which the policy was framed, as well as the analysis of the influence and interactions between cassava value chain stakeholder groups. Community engagements were also done with key informants to capture information regarding norms, customs and rules governing gender roles and ownership of key resources such as land within households. The data collection techniques that were employed at this level included a desk review (secondary data) and key informant. Table 3.1 shows the qualitative methods and the respondents that were interviewed during the study.

Desk study

This study involved the review of previous studies and policy documents on gender and agriculture in Tanzania. This included strategic government documents, commissioned research reports, academic articles, and to some extent policy briefs. Tanzanian agriculture policy documents and strategies on gender and agriculture were reviewed and they gave insights on institutional framework which governs gender and agriculture development. The Tanzanian National Strategy for Gender Development (NSGD) highlighted major issues of concern to gender inequality at the same time exposing the challenges that are faced. Such policy concerns included areas such as decision making and power, economic empowerment, food security and nutrition as well as community participation which were topical areas in this study. The Government policy on agricultural marketing of 2008, national agriculture policy of 2013 and the policy brief on women’s participation in agriculture were reviewed to provide a pointer on government’s thrust concerning production and marketing of agricultural produce.

Reports from IITA on cassava production, processing and marketing were also instrumental in providing direction on cassava producing areas, and other technical expertise with regards to processing and marketing. A report by Shayo (2015) on gender differences in earnings (wage gap), time use, and type of occupation, work conditions and access to employment in the cassava value chain in Tanzania were also reviewed. The report provided information on details regarding employment related issues within the cassava processing enterprises or groups, working conditions and time use patterns as well as other related activities. This information was useful in giving key details on women empowerment and the roles of women in the processing and marketing nodes of cassava value chains. The review of policy documents and reports gave insight about the key actors in the cassava value chain and their roles hence it significantly contributed to the mapping of the cassava value chain. Useful information was obtained regarding the institutional framework and how it influences the behaviour of men and women within households through the socially constructed norms and values.

Key informant interviews

Key informant interviews have been widely used in the field of development. In this context, they enabled us to acquire expert knowledge on key issues such as gender and agriculture upon which the study is grounded. Key informants were also useful in providing information pertaining to the value chain governance that is how institutional set-ups influence the cassava value chain map. They also provided information that guided the other techniques such as structured interviews. For instance, agricultural extension officers would provide information on the location of smallholder cooperative cassava processors. This technique was key to investigating issues pertaining to policy, input supply, cassava processing and to some extent marketing, particularly when we were targeting actors such as large scale buyers.

I conducted key informant interviews with resource people, whose knowledge of gender issues; cassava production, processing and marketing were valuable to the study. I selected key informants based on their knowledge, willingness and experience of the subject area and also their availability. A total of twenty-three (23) key informants were identified and interviewed. These included two agronomists (2) who provided information pertaining to input supply; planting, cassava diseases, effects of drought weeding, harvesting and processing of cassava; agricultural economist regarding agricultural policy issues, marketing and processing; large scale cassava buyer; a scientist from IITA, and a local inputs supplier.

The agricultural economist provided information regarding agricultural policy issues, gender and agriculture as well as marketing of crops. The agronomist provided information concerning agronomic practices involving cassava, challenges such as diseases, drought as well as extension information. The large scale buyer and input supply were useful with information regarding local input purchasing, local cassava marketing and processing channels, local gender dynamics in marketing as well as the challenges faced in buying inputs, processing and marketing. Each interview was conducted face-to-face and lasted approximately 45-60minutes in duration. There were guiding open-ended questions which also allowed the responded to explain other issues and even bring in new relevant ideas that may not have been asked. One characteristic of these interviews is that the respondents were self-motivated and enjoyed the discussion to such an extent that they provided useful and authentic information.

Key informant interviews were done to agricultural economists (3) in Dar es Salaam; gender specialist (1), agricultural extension officers (3), director agricultural extension (1) at Kizimbani research institute in Zanzibar. In Geita two agricultural extension officers were interviewe

Micro-level research

My study is primarily reliant on data that are collected at the micro level as guided by the Harvard Analytical Conceptual Framework which emphasises the collection of household level data in a gender analysis. This is because it is at the micro-scale that the most extreme variation exists within the household, because there are no unitary household preferences which are mainly divided along gender axis. The micro level scale is also the scale with the most power to affect people’s behaviour, since this is shaped by power struggles within households and therefore I argue that this is the scale at which we need to focus considerable attention. Within this scale, we have opted to examine women’s and men’s domestic roles and how the intra-household power dynamics influence control of resources, benefits sharing and participation in cassava value chain nodes.

At the household level this study was grounded on rural people’s own reports of their livelihoods and cassava value chain activities in their households. A case study approach was used to investigate information on the profile of cassava production, processing enterprises focusing mainly on types of resources owned, different gender positions, roles and responsibilities, stages involved in cassava processing activities, packing and storage facilities, as well as the sources of water and energy. Structured interviews, direct observations, extended household visits and focus group discussions were used to collect data at micro level.

Multistage random sampling was employed following purposive sampling of study sites. Simple random sampling then followed in each village to select the respective household heads for interviewing. A list of farmer names involved in cassava production was compiled by the agricultural extension officers’ who were stationed in each respective study area. Simple random sampling was then employed to select the final respondents in each village. The study adopted the participatory research approach that involved focus group discussions and extended household visits. This approach enabled sequential reflection and action carried out by the local people as well as enabling them to plan, share and analyse their knowledge of their local environment and conditions.

The enumerators as well as the focus group discussion moderators were experienced Agriculture Extension Officers who were stationed in the respective study areas. The recruitment of extension officers enabled us to get consent from farmers easily at the same time building trust with the communities, allowing us to collect reliable data. Farmers were comfortable to share their information with an extension officer they had a long standing relationship with. From each study area four enumerators were engaged constituting of both male and females.

Dedication

Declaration

Acknowledgements

Abstract

List of Tables

List of Figures

List of Acronyms

Chapter 1: Introduction and background

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Background to the study

1.2.1. Significance of agriculture in Tanzania

1.2.2 Understanding the cassava value chain

1.2.3 Women in agriculture and cassava value chains

1.3 Statement of the problem

1.4. Research questions

1.4.1. Main research question

1.4. 2. Minor research questions

1.4.3 Main objective

1.4.4 Specific objectives

1.5 Organisation of the thesis

Chapter 2: Literature review on cassava value chains, gender and agriculture policy framework in Tanzania

2.1 Introduction

2.2. The Conceptual framework

2.2.1: Harvard analytical tool: Activity profile.

2.2.2: Harvard analytical tool: Access and control profile

2.2.3: Harvard analytical tool: Influencing factors

2.2.4 Value chain analysis

2.3.: Cassava as a strategic staple food crop

2.3.1 Importance and contribution of cassava to food security and economy

2.3.2 Cassava crop production

2.3. 3 Cassava processing

2.3.3.1 Peeling of cassava tubers

2.3.3.2 Grating of peeled cassava

2.3.3.3 Drying and dewatering

2.3.3.4 Cassava products

2.3.4 Types of food value chains

2.3.4.1 Traditional food value chains

2.3.4.2 Modern-traditional food value chains

2.3.5 The cassava traditional food value chain

2.3.6 Agriculture food value chain governance

2.3.7 Constraints to cassava value chain development

2.4 Gender and agricultural value chains

2.4.1 Gender power dynamics in agricultural commodity value chains

2.4.2 The role of women in cassava value chains

2.4.3 Women’s empowerment in agriculture

2.4.4 Status of women’s empowerment within households

2.4.5 Measuring women empowerment in agriculture value chains

2.5 Women participation in the cassava value chains

2.5.1 The role of women in the cassava value chain

2.5.2 Status of women’s participation in agriculture value chains

2.5.3 Factors affecting participation of women in cassava value chains

2.6. Chapter summary

Chapter 3: Research approach and methodology

3.1 Introduction

3.2 Research design and sampling

3.3 Macro-level research

3.4 Micro-level research

3.5 Challenges encountered and how they were handled

3.6 Ethical considerations

3.7 Data analysis

3.8 Chapter summary

Chapter 4 Gender, Agriculture Policy and case study site characterisation in Tanzania

4.1 Introduction

4.2 Climatic and agro-ecological conditions of Tanzania

4.3 Biophysical case study site characterisation

4.4 The policy framework for gender and agriculture in Tanzania

4.5 Gender and agriculture in Tanzania

4.6 Chapter summary

Chapter 5 Mapping cassava food value chains in Tanzania’s smallholder farming sector

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Analysis of cassava value chains and intra-household gender dynamics

5.3 The cassava value chain map

5.4 Chapter summary

Chapter 6 Gender and empowerment in cassava food value chains

6.1: Introduction

6.2: The 5DE sub-index of women’s empowerment in agriculture (WEAI)

6.3 Empirical description of 5DE domains and indictors

6.4 Computation of 5DE empowerment index

6.5 Chapter summary

Chapter 7 Factors influencing smallholder farmers’ participation in the cassava value chains in Tanzania

7.1 Introduction

7.2 Empirical analysis and description of variables used

7.3 Description of explanatory variables

7.4 Factors affecting men and women participation in cassava production node

7.5 Factors affecting market participation of farmers in the cassava value chain

7.6 Participation of women and men as processors in the cassava value chain

7.7 Chapter summary

Chapter 8 Situating neglected cassava value chains and marginalised women in a household gender based conceptual framework

8.1 Introduction

8.2 Existing gender analysis conceptual frameworks

8.3 Developing the household gender-based conceptual framework

8.4 Empirical description of the guiding framework questions

8.5 Components of the conceptual framework

8.6 Chapter summary

Chapter 9 Discussions, conclusions and policy implications

9.1 Introduction

9.2 Discussion

9.3 Conclusion

9.4 Implications for policy

9.5 Scope for further study

APPENDICES

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT