Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

SOCIAL CAPITAL IN COMMUNITY LIFE: A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

How does social capital affect the life and development of communities? The debate on social capital indicates a wide variety of possibilities. By looking at a number of different contexts, including the northern industrialised contexts, I will show that social capital is manifested in many processes in different contexts. My conclusions in the discussions that follow are meant to be both an aid for community development strategies as well as a platform to raise questions regarding the role of social capital in rural community development.

The family

The family can be regarded as a source of social capital in its own right (Mayoux, 2001 :450). Considering Putnam’s (1993) view of social capital as mutual obligations and trust, and Coleman’s (1988) view of social capital as a social structural resource (see section 2.3), the family seems to fit perfectly into the theoretical paradigm of social capital. Studies conducted on family structures and education agree that the family is a social resource (Lichter, Cornwell and Eggebeen, 1993 : 53 – 75; Lehning, 1998 : 221 – 242). Lichter, et al (1993 : 54 – 55) refer to Coleman (1988) who regards social capital within families as mutual obligations and interpersonal relationships between parents and their offspring. Putnam (1993 : 175) notes that ‘… kinship ties have a special role in the resolution of collective action’ and, in a later publication (1995 : 73), Putnam describes the family as ‘… the most fundamental form of social capital’.

Norms and values

For community development efforts to be successful, community members must have a norm which embodies a positive view of their own potential (Van Willigen, 1993 : 95). Besides the norms found in families and communities, whether small tribal groups such as those found in rural Africa or complex modern societies, the existing social capital found in communities seemingly displays unique sets of norms and values. Weede (1992 : 393) describes these regulatory norms and values as codified laws which encompass the large areas of social life. According to Putnam (1993 : 172), the norm of general reciprocity is a highly productive component of social capital.

Trust

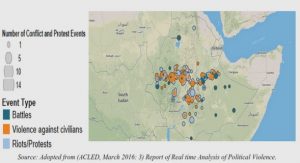

There appears to be widespread consensus in literature that trust is an important indicator for social capital (Coleman, 1990 : 91 – 103; Lowndes, 2000 : 535 – 536; Kaase, 1999 : 2 – 14; Marske, 1996 : 113; Putnam, 1993; Lehning, 1998 : 237; Onyx and Bullen, 2000 : 24; Pye, 1999 : 765; Fukuyama, 1995a; Weede, 1992 : 392). Kaase (1999 : 4 – 8) distinguishes between political trust and interpersonal trust. When trust is absent in a community, whether political or interpersonal, the potential for dysfunctional conflict may increase. All over the world, but particularly in rural Africa, wars and ethnic conflict between countries and between communities can be traced to a lack of trust between ethnic groups. Bourdieu (1986), Coleman (1990) and Putnam (1993, 1995) capture trust in their definitions of social capital (see section 2.3).

Cooperation and participation

Chetkov – Yanoov (1986 : 26) notes that the term ‘cooperation’ originates from Latin and means operating or working jointly with another person or group in order to promote a common objective (or purpose), produce the same result, or achieve a desired result more efficiently. From the theoretical views presented earlier (2.3), cooperation and participatory actions appear to be essential for the establishment of social capital in communities. Levi (1986 : 14) distinguishes between a ‘community’ and ‘cooperatives’ and asserts that these two social systems are potentially complementary. With regard to rural communities, the geographical boundaries provide a sense of security, but, internally, as Oosthuizen and Van der Worm (1991 : 15) also observe, cooperative behaviour exists as a result of subsystems in interaction with each other (2.2.2).

Partnerships

The theoretical views presented earlier (2.3) relate social capital to the individual although the presence of partnerships is in this study is regarded as potential social capital in a community. Partnerships provide opportunities for the attainment of economic benefits. In addition, there are economic and social ways in which partnerships can be defined. Both are used in this discussion, although socio-economic partnership formation may occur between people, organisations, communities and between countries.

TABLE OF CONTENTS :

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- ABSTRACT

- OPSOMMING

- LIST OF TABLES

- LIST OF ANNEXES

- CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION AND ORIENTATION

- 1.1 INTRODUCTION

- 1.2 STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

- 1.2.1 Economic needs at the centre of development

- 1.2.2 Social capital is available in the developing world

- 1.2.3 Social capital is frequently overlooked

- 1.2.4 Communities are often unaware of their potential social assets

- 1.3 OBJECTIVES

- 1.4 RESEARCH AREA AND RESEARCH GROUP

- 1.5 OVERVIEW OF THE THESIS

- CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE STUDY: SOCIAL CAPITAL AND NEED .. SATISFACTION

- 2.1 INTRODUCTION

- 2.2 TERMINOLOGY

- 2.2.1 Development

- 2.2.2 Community development

- 2.2.3 Paradigm

- 2.2.4 Social capital

- 2.2.5 Socio-economic resources

- 2.2.6 Needs

- 2.3 THEORETICAL VIEWS OF SOCIAL CAPITAL

- 2.3.1 Pierre Bourdieu’s view: relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition

- 2.3.2 James Coleman’s view: social capital as resourceful relationships

- 2.3.3 Robert Putnam’s view: social organisations and connections

- 2.3.4 Other theoretical viewpoints

- 2.4 SOCIAL CAPITAL IN COMMUNITY LIFE: A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

- CHAPTER THREE: DESCRIPTION OF CONTEXTS OF

- RESEARCH

- 3.1 INTRODUCTION

- 3.2 THE CONTEXT OF SOUTH AFRICA

- 3.2.1 Past social, political and economic context

- 3.2.2 Current social political and economic context

- 3.2.2.1 Demography

- 3.2.2.2 Economic context

- 3.2.3 Social disintegration and collective needs in South Africa

- 3.2.4 National community development

- 3.2.5 Social capital on the broad national level

- 3.3 A PROFILE OF LIMPOPO

- 3.3.1 Background

- 3.3.2 The institutional situation

- 3.3.5 Social connections

- 3.3.5.1 Marriages

- 3.3.5.2 Family ties

- 3.3.4.3 Immediate family

- 3.3.5.4 Extended family

- 3.3.6 Housing

- 3.3.6.1 Types of housing and distribution

- 3.3.6.2 Occupation of houses and informal settlements

- 3.3.6.3 Respondents’ views on old age homes

- 3.3.7 Health

- CHAPTER FOUR: EMPIRICAL STUDY

- CHAPTER FIVE: INTERPRETATION OF RESULTS

- CHAPTER SIX: CONCLUSIONS

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT

A RECONCEPTUALISATION OF THE CONCEPT OF SOCIAL CAPITAL: A STUDY OF RESOURCES FOR NEED SATISFACTION AMONGST AGRICULTURAL PRODUCERS IN VHEMBE, LIMPOPO