Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Introduction

The previous chapter discussed the literature review regarding the topic being studied. In Section 1.10, the choice of research methodology for this study was discussed in brief. Hermon and Schwartz as quoted by Ngulube (2003:194) argue that LIS (including archival science and records management) scholars have the tendency to concentrate on the findings of their research without examining the methodology used. Equally neglected by most LIS scholars are issues of reliability and internal validity, as well as ethical considerations when conducting research (Jane 1999:211; Neuman 2003:29; Ngulube 2003:1947). In an informetrics analysis of research procedures utilised by Master of Information Studies students at the University of Natal (1982-2002), Ngulube (2005:127) found that most of the theses ignored the evaluation of the research procedures. The action of the students is contrary to the argument put forward that for research in LIS to contribute to theory and improve planning, practice and decision-making, it should rely on objective methods and procedures. Indeed, as Jane (1999:211) would concur, the production of valid knowledge hinges upon the method of research used. This sentiment is echoed by Fielden (2008:7) and Ngulube (2005:127) when stressing that methods employed by researchers are key to the quality of their research outputs. Describing the methods used by a researcher is essential because it enables other researchers to replicate and test methods used in the study.

Furthermore, a detailed and accurate account of research procedures may also enable readers to explain differences in findings among studies dealing with the same research question in terms of differences in procedure (Jane 1999:211; Ngulube 2003:194; 2005:128). In this regard, readers will make use of the findings and recommendations of LIS research if they have some degree of confidence in the quality of work described and the accuracy of inferences drawn. Therefore, the purpose of this chapter is to present the selected research methodology and the data collection techniques that guided the description and interpretation of this study. The chapter covers justification of research paradigm, research approach, population of the study, sampling method and data collection tools which helped the researcher in answering the research questions, evaluation of research methodology, as well as ethical issues which were considered when conducting this research and issues of reliability and validity of data collection.

Research design

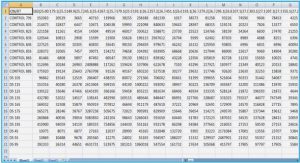

Jane (1999:211) and Leedy and Ormond (2005:1) define research as “a systematic process of collecting, analysing, and interpreting data in order to increase our understanding of the phenomenon about which we are interested or concerned.” In line with this definition, in LIS discipline, scholars are concerned with the exploration of the nature of the information phenomenon. Table 3.1 provides a classification of the types of research according to category, methodology, purpose and time dimension.

Categories of research

According to Neuman (1997:21) research can be divided into categories as reflected in Table 3.1, that is, according to what it is used for. These categories are basic research (research that tends to expand fundamental knowledge) or applied research (research that tends to solve specific pragmatic problems). Basic research is used to enhance fundamental knowledge about social reality while applied research is used to solve specific problems, or if necessary, try to make specific recommendations. According to Neuman (1997:22-23) basic research tries to support or reject theories by explaining social relationships, as well as interpreting changes in communities in order to enhance new scientific knowledge about the world. Applied research is descriptive in nature and its main advantage is that it can be applied immediately after having obtained the results (Jane 1999:211). The major goal of applied research is to gather information that contributes to the solution of a societal problem. Unlike applied research, basic research does not emphasize the solving of specific or real problems. Instead, the main distinguishing feature of basic research is that it is intended to generate new knowledge. This is not to underestimate the fact that although problem solving is not the goal of basic research, its findings could eventually be useful in solving a particular problem. ‘The relationship between variables and statistical significance are fundamental to basic research, whereas both practical significance and statistical significance are important to applied research’ (Bickman & Rog 1998:xi). In this study, a basic research approach was adopted, as the study concentrates more on expanding knowledge in the area of the relationship between records management and auditing, as well as proposing a framework to embed records management into the auditing process. It is envisaged that such a framework will assist governmental bodies in achieving clean audit results, thereby solving the challenges of disclaimers.

Purpose of research

Social research serves many purposes. Three of the most common and useful purposes as identified by Neuman (2003:29) are: exploratory (explore a new topic), descriptive (describe a social phenomenon) and explanatory (explain why something occurs). Although a given study can have more than one of these purposes examining them separately is useful as each has different implications for other aspects of research design. A large proportion of social research is conducted to explore a topic or to provide a basic familiarity with that topic. This approach is typical when a researcher examines a new interest or when the subject of study itself is relatively new. Exploratory studies are most typically done for the following reasons: (i) to satisfy the researcher’s curiosity and desire for better understanding, (ii) to test the feasibility of undertaking a more extensive study, (iii) to develop the methods to be employed in any subsequent study, (iv) to explicate the central concepts and construct a study, (v) to determine priority for future research and (vi) to develop new hypotheses about existing phenomena (Leedy 1997:204; Taylor 2005:94).

Another major purpose for many social scientific studies is to describe situations and events. The researcher observes and then describes what was observed. The primary purpose is to analyse trends that are developing, as well as the current situation. Therefore, data derived can be used in diagnosing a problem or advocating a new programme (Taylor 2005:93). Sources of data in descriptive studies are numerous, such as: surveys, case studies, trend studies, document analyses, time-and-motion studies and predictive studies. As indicated above, the third general purpose of social scientific research is to explain things. Neuman (2003:29) notes that while studies may have multiple purposes, one purpose is generally dominant. The dominant purpose of the present study was exploratory and descriptive. In other words, the research sought to examine, inter alia, trends of audit findings in relation to records management, role of records management in the auditing process and risk management and involvement of records management practitioners in the audit committees of governmental bodies in South Africa, as well as to propose a framework for embedding records management into the auditing process.

Research approach

Many researchers identify two major methodological paradigms that have dominated the social research scene as qualitative and quantitative (Amaratunga, Baldry, Sarshar & Newton 2002:17; Creswell 2006; Leedy & Ormond 2005:135; Mouton & Marais 1989:156). Each of these approaches (qualitative and quantitative) has been linked to one of the metatheoretical traditions, that is, the quantitative approach is linked to positivism and the qualitative approach to phenomenology or interpretevism (Mangan, Lalwani & Gardner 2004:565). Table 3.2 outlines comparisons and differences of features of qualitative and quantitative approaches to research. The third paradigm is identified by researchers as mixed method research (MMR) in which researched combine both qualitative and quantitative (Creswell 2006).

Qualitative research

Mouton and Marais (1989:157) define qualitative as all non-numeric data words, images and sounds. Qualitative research emphasises meanings (words) rather than frequencies and distributions (numbers) when collecting and analysing data. It is a way of collecting information on the knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of the target population (Ramos & Ortega 2006:11). Qualitative research designs involve case study (where a particular individual, programme, or event is studied in depth for a defined period of time), ethnography (where the researcher looks at an entire group – more specifically, a group that shares a common culture – in depth), phenomenological study (a study that attempts to understand people’s perceptions, perspectives and understandings of a particular situation), content analysis (a detailed and systematic examination of the contents of a particular body of material for the purpose of identifying patterns, themes or biases) and grounded theory study (uses a prescribed set of procedures for analysing data and constructing a theoretical model from them) (Leedy & Ormond 2005:135-141). Qualitative research involves the use of qualitative data such as in-depth interviews, document and participant observation to understand and explain social and cultural phenomena (Creswell 2006). It often focuses on viewing the experiences from the perspective of those involved. It involves analysis of data such as words (from interviews), pictures (from video), or objects (from an artefact) (Mouton & Marais 1989:158).

Qualitative researchers typically locate themselves within an interpretevistic tradition, albeit they also often hold a realist’s assumptions about the world and the contextual conditions that shape and embed the perspectives of those they seek to study. Primarily qualitative research seeks to understand and interpret the meaning of situations or events from the perspectives of the people involved and as understood by them. It is generally inductive rather than deductive in its approach, that is, it generates theory from interpretation of the evidence, albeit against a theoretical background. Methods of qualitative research include: observation, interviews, historical narrative, case study, documentary analysis and action research.

Quantitative research

Quantitative research, on the other hand, is data or evidence based on numbers (Leedy 1997:104). It uses mathematical analysis. It is the main type of data generated by experiments and surveys, although it can be generated by other research strategies too such as observations, or analysis of records. It includes the use of closed survey methods and laboratory experiments and usually ends with confirmation or disconfirmation of the hypotheses tested (Creswell 2006). Quantitative research places the emphasis on measurement when collecting and analysing data. It is defined, not just by its use of numerical measures, but also because it generally follows a natural science model of the research process measurement to establish objective knowledge. Generally it makes use of deduction, that is, research is carried out in relation to hypotheses drawn from theory. Methods of data collection in quantitative research include: surveys (questionnaire), structured interviewing, structured observation, secondary analysis and official statistics, content analysis according to a coding system, quasi-experiments, classic experiments (Leedy & Ormond 2005:135). Table 3.3 outlines the strengths and differences of qualitative and quantitative research.

SUMMARY

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

DEDICATION

DECLARATION

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION: PUTTING THINGS INTO PERSPECTIVE

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Background to the study

1.3 Contextual and conceptual setting

1.4 Framework for the study

1.5 Problem statement

1.6 Research purpose and objectives

1.7 Justification and originality of the study

1.8 Scope and delimitation of the study

1.9 Definitions of key terms

1.10 Research methodology

1.11 Structure of the thesis

1.12 Summary .

CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW: THE ROLE OF RECORDS MANAGEMENT IN THE AUDITING PROCESS, RISK MANAGEMENT AND GOOD GOVERNANCE

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Purpose of literature review

2.3 A historical perspective of the relationship between record-keeping, auditing and corporate governance

2.4 The components of corporate governance in the public sector

2.5 The role of records management in demonstrating accountability, transparency and good governance

2.6 The implications of records management towards risk mitigation

2.7 Summary

CHAPTER THREE RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

3.1 Introduction

3.2 Research design

3.3 Research procedures

3.4 Reliability and validity of the instruments

3.5 Ethical considerations

3.6 Evaluation of research methods

3.7 Summary

CHAPTER FOUR PRESENTATION OF DATA

4.1 Introduction

4.2 Response rate and participants’ profile

4.3 Data presentation

4.4 Summary

CHAPTER FIVE INTERPRETATION AND DISCUSSION OF RESEARCH FINDINGS

5.1 Introduction

5.2 The role of records management into the auditing process

5.3 The contribution of records management towards risk mitigation

5.4 Analysis of the general reports of AGSA (2000/01-2009/10) in relation to findings on record-keeping

5.5 Establishment of audit committees in governmental bodies

5.6 The relationship between records management and corporate governance

5.7 Summary .

CHAPTER SIX SUMMARY OF FINDINGS, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

6.1 Introduction

6.2 Summary of research findings

6.3 Conclusions about research objectives

6.4 Recommendations

6.5 Proposed framework

6.6 Implication for theory, policy and practice

6.7 Further research

6.10 Final conclusion

List of references

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT

FOSTERING A FRAMEWORK TO EMBED THE RECORDS MANAGEMENT FUNCTION INTO THE AUDITING PROCESS IN THE SOUTH AFRICAN PUBLIC SECTOR