Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

The quality of cooperation between employers and workers’ representatives

The first chapter analyses the career trajectory of works council representatives in Germany. It builds on a literature which is rather thin. For long, most of the economic literature in industrial relations has indeed focused on unionized forms of representation. Unions are entitled to sign collective agreements and, as such, are the most important labour partner to employers. They have the power to organise strikes and, in most institutional cases, are also headed by an organisation at the branch or national level – which sometimes constitutes a monopoly of labour representation at these scales. If well organized, these organisations are therefore able to impose common economic conditions on large sections of the economy.

For these reasons, unions have long been analysed per the monopoly model of Dunlop (1944). According to it, unions would negotiate higher wages than in the frictionless equilibrium, thereby leading firms to respond by a decrease in employment. The revival of interest into other forms of labour representation has taken place in the waves of Freeman’s paper (1976).

Freeman shows that coordination between employers and unions can also generate surplus by avoiding some market failures. The paper led to a large amount of empirical research trying to disentangle which of the rent-seeking or rent-generating sides of unions dominate (for a review, see Guyot and Ferracci, 2015).

By bringing back attention on the possible gains of labour-employer cooperation in the context of a generalized decrease of union coverage, Freeman’s paper also oriented the literature towards works councils. In most countries, their entitlements to negotiate on most conflicting issues (wage scales, job classification, working time, …) are indeed limited. Works councils are generally confined to issues related to the organisation of production and their ability to seek rents is therefore thought to be more limited than unions. A vast number of papers have therefore estimated the impact of works councils on firms’ productivity and wages (FitzRoy & Kraft, 1990, 1987, 1985; Hübler & Jirjahn 2003; Ellguth et al. 2014; Brändle, 2017).

As important as they are, we know however little on how the actors leading the negotiations themselves fare in the firm. Yet their career evolution brings a lot of information on the quality of labour-employer cooperation. To my knowledge, only Breda (2014) and Breda and Bourdieu (2016) have raised the issue. They explain that firm-level representatives play two bargaining games with their employer: one for their own account like any other employee negotiating her wage, another in the name of their colleagues. Breda and Bourdieu further show that the two games are not independent. A rational employer has incentives to discriminate against (respectively buy) most vehement (resp. collaborative) representatives in the first game to maximise its rent in the second game. Turning to empirics, the authors find proof of such ‘strategic discrimination’. Exerting the main representative mandate at the firm level in France is associated with a drop of 10% in wage. Delegates of the most vehement union would lose up to 20% of wage.

If we are to believe public discourse as well as employers’ estimation of the quality of employer-labour relations in France and Germany (see figure 1), discrimination against workers’ representatives is expected to be null, or at least much lighter, in Germany. The question takes particular importance given the recent evolutions of the German economy. It is interesting to take a detour to explain why, before presenting the main results of the chapter.

Once qualified “the Sick man of Europe” in the late 1990s to early 2000s, (The Economist, 2004) Germany has become the “Economic Superstar” of the continent (Dustmann et al., 2014a). The Great Recession was indeed short lived in the country and Germany is now experiencing full employment (3.4% of unemployment in 2018). Three competitive explanations have mostly been evoked to explain the German success: (i) the impact of the Hartz reforms on the Labour market (ii) the fact that the Euro would benefit Germany thanks to its export-led economy able to produce high-quality manufactured products

In their 2014 article, Dustmann et al. show how the German system of industrial relations has opened the way to competitiveness gains since the 1990s. The traditional model of collective bargaining in Germany is based on two legs. At the branch level, strong unions bargain with employers on most strategic issues such as wage growth, job classification or working time. At the firm level, works councils are entitled with the strongest power in the West. Power sharing within companies can take the form of joint-management or co-determination (Crifo and Rebérioux, 2019)4. In Germany, both are well developed: works councilors are very well represented in supervisory boards and have co-determination rights on some individual staff movements as well as on overtime or on plans of reduced working time. Branch-level bargaining however dominates: hierarchy of norms5 applies and the power to call for strikes is limited to branch-level unions who may use it to flex their muscles when the 4-year bargaining rounds take place. The system relies on contracts and mutual agreements between unions, employers’ associations and works councils rather than on legislations. According to Dustmann et al (2014a), it is this contractual feature that has put the country in good position to recover from both its economic crisis of the early 2000s and the Great Recession.

In the late 1980s, coverage of employers’ associations began to fall and, partially in response to this phenomenon, opening clauses to branch agreements have multiplied. If their content strongly varies, overall, these clauses have allowed employers to implement wage restraints at the periphery of the economy from as early as the 1990s. From 1990 to 2002, pay rises are therefore very limited for the whole wage distribution in the sectors of non-tradable goods and for the first deciles of the distribution in the sector of tradable services. At the same time, strong productivity gains were observed in the manufacturing sector and reliance on low-cost imports of intermediate goods from Eastern Europe increased. As a result, the unit labour cost in terms of end product6 has fallen by 10% from 1995 to 2002 despite the robust pay rise for all the wage distribution in the manufacturing core. When the Hartz reforms are passed and the Eurozone is implemented, Germany has already broken away from its competitors in terms of unit labor costs in the manufacturing export sector. If a deepening of wage moderation with negative growth rates at the bottom of the income distribution can be seen after 2003, no break can be clearly identified. Overall, in Germany, the unit labour cost has continuously dropped between 1995 and 2012 (-30%) to the contrary of its main economic competitors.

The flexibility brought by the contractual nature of industrial relations in Germany has been widely considered as an important source of explanation for its quick recovery from the Great Recession (Bellmann et al, 2016; Amossé et al., 2018). In 2007, at a time when the economic crisis was triggering, the manufacturing core of the German economy benefited from a competitiveness reinforced by 15 years of wage moderation at its periphery. Furthermore, job-retention agreements have accelerated the exit of the crisis.

Importantly however, the cooperative feature of the German model of industrial relations played an ambiguous role in the ‘German miracle’. In the early 1990s, coverage rates of unions and employers’ associations were decreasing and both institutions were struggling to limit their loss. At the same time West German employers were gaining in bargaining power due to the credible threat of outsourcing production towards East Germany and Eastern Europe. Unions and employers’ associations were therefore constrained to accommodate employers’ will for flexibility in order to prevent firms from massively leaving their business association which would cause the system to dismantle. The extent to which the decentralization of collective bargaining is the result of labour-employer cooperation at the branch level should therefore be nuanced. At the firm level, the strength of cooperation between works councilors and employers is not clear-cut either. Pallier and Thelen (2010: 126) have noted that the process of decentralization “involved an intensification of cooperation between managers and workers in leading firms (in Germany’s manufacturing sector)”. In the service sectors however, where wage restraints proved the strongest, it is unclear how cooperation evolved. In particular, in the absence of a national minimum wage before 2015, the development of atypical work in the 2000s – in part fostered by the Hartz reform on mini jobs – has put downward pressure on the bargaining power of labour representatives.

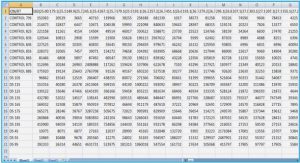

The first chapter of this PhD aims at bringing a new light on the quality of cooperation between employers and labour at the level of the firm. It is entitled The impact of works council membership on wages in Germany: a case of strategic discrimination? In this chapter, I measure the causal impact of works council mandates on wages, separately in the manufacturing sector and in the service sector in Germany. The data comes from the German Socio-Economic Panel, which is a general representative survey at both the household and the individual levels. To my knowledge, it is the only source of data providing information on both works council membership and wages in Germany. I use waves 2001, 2003, 2006, 2007, 2011 and 2015 when respondents are asked whether they are members of a works council.

The main method of identification of Chapter 1 is an OLS regression with individual fixed effects of the hourly gross wage on works council membership. I control for union membership: about two thirds of works councilors are unionized in Germany and it therefore matters to disentangle the effects of the two institutions. The regression sample is composed of full-time workers aged between 20 and 64 and employed on open-ended contracts in firms with more than 5 employees. Civil servants are further dropped. To ensure that results are not driven by agents changing firm or by firms’ unobservable characteristics, for each individual, I restrict the sample to the longest of her working spells within a firm. The identifying observations are therefore workers who change status (i.e. are voted in or out of the works council) while remaining in the same firm.

Overall, works council membership has no significant impact on wages. Yet, it appears that the relation goes in fact in diverging directions according to the sector. In the manufacturing sector, all other things being equal, individuals observed both in and out of office (switchers) earn about 4.5% more in office than out of office. In the private service sector – from which I excluded banking and insurance which display very particular patterns of industrial relations – representatives suffer a penalty of 4%. The results are mostly driven by a particular evolution in ‘pure wage’ rather than in the number of working hours declared. As for union membership, I find a slight negative impact on wages overall, which is fully driven by the private service sectors. In these sectors, union membership is associated with a drop of around 6.5% in hourly gross wage.

The second result of this chapter is that, in the manufacturing sector, workers running for professional elections are not comparable to their colleagues. Their wage trajectory before elections is indeed worse than the one of their colleagues. Taking this into account inflates the final premium to +7% in the sector. I cannot lead a similar procedure in the case of the service sector because of data limitation. I nevertheless bring elements showing that, in this sector as well, the association between works council membership and wages should be understood as a deliberate firm policy targeting elected representatives.

This is the third result of this paper. I find that the impact of mandates on wages is driven by politically involved works councilors in both sectors. In the chapter, political involvement is successively measured via two different channels: (i) unionization; (ii) whether the respondent leans towards one party in the long term. The latter result is put into perspective by building on the context and on the literature of political science.

The first chapter of the thesis therefore brings elements suggesting that the strategic discrimination against workers’ representatives evidenced by Breda and Bourdieu in the case of France is also taking place in Germany. Despite the two countries exhibiting very different models of industrial relations, the level of negative discrimination against works councilors found in the service sector in Germany is closed to the one found overall in France. The main difference relates to the positive impact of mandates on wages in the manufacturing sector. The intensified cooperation noted by Pallier and Thelen (2010) between representatives and employers in the sector could have brought flexibility gains against pay rises.

Apprenticeship training in France and Germany

The economic literature has shown that apprenticeships explain a large part of the cross-country variance in youth unemployment (Van der Velben and Wolbers, 2003). As such, they “have been in the spotlight in many OECD countries, not only in the aftermath of the Great Recession, but also following recovery” (OECD, 2018: 15).

The cases of France and Germany exemplify these statements. Figure 4 shows that the youth-to-adult unemployment rate is much larger in the former while, as previously mentioned, apprenticeship training involves vocational students twice more often in the latter. The public discourse in France urging to copy the German model of apprenticeship training is therefore largely shared. To the exception of the radical left and of some unions7, this policy constitutes a wide consensus. Yet it does not fully rely on scientific research. Before turning to the economic literature to show why, it is interesting to take a detour to briefly explain why work-based training is much more developed among vocational tracks in Germany than in France.

The explanation goes back to the unequal fate of collective organisations in the 18th and 19th centuries. In France, the Allarde decree and the Le Chapelier law abolished corporations in 1791 and outlawed any training for the youth if collectively set up. Rooted in a liberal political philosophy, this legislation clamped down on the main producers of norms in VET matters (Lemercier, 2007). The result was a rise in unregulated on-the-job training offering no contract or diploma (Lequin, 1989; Troger, 1993). Conversely, in Germany, laws hostile to corporations in the mid-19th century had little effect and only applied for a short period. Indeed, at that time, the growing social democratic claims of the working class on one hand and the promotion of liberal reforms by the elite on the other hand were weakening the Conservatives and Centre parties (Thelen, 2004). They found support in the independent craft sector to back the Establishment against some clientelist privileges. These included the institutionalisation of craft chambers. In 1897, handcraft firms were required to register to them and, in 1908, they were granted a monopoly for apprenticeship training (ibid).

Facing a common need in skilled workers at the time of industrial revolutions but surrounded by a different institutional context, firms of strategic sectors (engineering industries in particular) therefore lobbied their respective State for different policy changes regarding vocational training from the early 20th century to the 1960s. In France, in the absence of branch agreement, skills learnt in factory schools were of disparate quality and barely portable. Moreover, investment costs that firms endured for these schools were not always bringing the expected returns. Numerous smaller firms not engaged in training were indeed able to offer higher wages thereby ‘poaching’ graduates (Rojot, 2014). Despite its liberal aspirations, the ‘Association Française pour le Développement de l’Enseignement Technique’ (AFDET) – set up in 1902 and mostly funded by the metal industry – therefore called for stronger State intervention to better standardize diploma and to limit ‘poaching’ behaviors. Lobbying pressure was successful since a national CAP diploma, the requirement to train apprentices out of the workplace and an ‘apprenticeship tax’ were set up at the national level in the inter-war period (Brucy and Troger, 2000; Dayan, 2013).

In Germany at the same time, modern firms were mostly struggling to attract the brightest students to their in-house schools (Thelen, 2004). For students and their parents, obtaining a diploma after graduation that is valuable outside of the training firm is generally a precondition to start an apprenticeship (Webb and Webb, 1897). Yet, as previously mentioned, craft chambers then benefited from a monopoly to sanction apprenticeship diplomas. As a result, the lobbying group DATSCH – set up in 1908 by the Verein Deutscher Ingenieure (VDI) and the Verband Deutscher Maschinen und Anlagenbau (VDMA) – pressured the State to recognize the right for business and trade chambers to collectively organize and sanction apprenticeships (Thelen, 2004). The claim turned into law in 1935. The choice of imperial Germany to provide craft chambers the monopoly to train apprentices therefore initiated the path towards strong levels of subsidiarity in VET matters.

In France, State intervention in vocational training deepened after WWII. Against the influential French Communist Party (PCF), the anti-communists unions F.O. and F.E.N became natural allies to the Socialists who were then heading the General Directorate of Vocational Education (DGET) (Troger, 1989, 1993). These unions were opposed to the working-class ethos of the PCF. They therefore urged the DGET to privilege full-time vocational tracks in public schools over apprenticeships (ibid). This process resulted in the integration of the colleges for apprenticeships under the management of public high schools in the early 1960s as well as in the development of vocational training via standard schooling. Large industrial firms did not oppose this trend (Charlot and Figeat, 1985). Net training costs were indeed growing because of both the costs of technological innovations and the low returns on investments stemming from poaching behaviours (Niell, 1954). Factory schools were also increasingly struggling to attract good students and proved not to be as flexible as expected relatively to public schools (Hatzfeld, 1996; Quenson, 1996 ; Gallet, 1996). The major role of the State in vocational training and the predominance of full-time vocational training over apprenticeships in France therefore take root in the post-war era. It benefited from the tacit support from strategic firms who had been unable to organise training collectively since the 1791 anti-corporatist laws.

This historical path has led to a larger importance of apprenticeship training among vocational tracks and a stronger involvement of social partners in its management in Germany than in France. The second chapter of this PhD thesis analyses where the track is the most efficient in terms of insertion on the labour market and job quality.

The economic literature has been prolix on the positive impact of apprenticeship training in French secondary education (Sollogoub and Ulrich, 1999; Simonnet and Ulrich, 2000; Issehnane, 2011) and, to a lower extent on its absence of impact in French higher education (Issehnane, 2011). But we know much less on the effect of apprenticehip training in Germany. Estimates of the overall effect on employment are positive but most research has used data from West Germany before 2000 (Winkelmann, 1996; Franz et al., 1997; Parey, 2012). To my knowledge, only Riphahn & Zibrowius (2016) have worked nationwide and over a more recent period. They focus on the difference between vocational and general studies, but one of their secondary outcomes refers to apprenticeships and they do not observe any effect on access to employment.

Chapter 2 is entitled Apprenticeship training, better labour market outcomes in France than in Germany. It mobilises data from the German Socio-Economic Panel and the French survey Génération to compare the impact of apprenticeship training on job market outcomes in the two countries between 1998 and 2013. The former data source has already been presented above. The latter is a representative survey of students exiting school for the first time for more than a year in France. The impact of apprenticeships is measured as the difference in outcomes between graduates from apprenticeship tracks and the other students. The independent variables exploited are the following: number of months unemployed the year after leaving school, time spent in full-time compared to part-time work during that twelve-month period, first observable full-time salary. The middle-run outcomes are the following: the likelihood to experience a continuous period of employment longer than 18 months in the three years after leaving school, the waiting time before this period, and the wage at its end.

The analysis is separately led on two cells in each country. They gather respondents according to their level of education before exiting school: (i) vocational secondary education; (ii) higher education. In France, definition of the control and the treatment groups are straightforward given that most diplomas can be taken via an apprenticeship track. In each cell, the treated group includes students which received their last diploma via apprenticeship training. In Germany however, apprenticeships in higher education remain marginal and chapter 2 therefore focuses on the traditional apprenticeship track at the upper secondary level. In the higher education cell, the treated group therefore includes students who obtained an apprenticeship diploma before graduating from higher education while the control group gathers all other graduates from higher education.

The first main result stems from an OLS regression. It shows that apprentices do better than school leavers in both countries. The advantage is however stronger in France. In terms of the unemployment rate in the year after leaving secondary school or higher education, the difference between the two countries is equivalent to about 6.75 pp more for France. On the longer run, apprenticeship is associated with greater stability in employment in both countries. The gain in speed to access stability is however stronger in France. Interestingly, the channel explaining the good outcomes of apprentices differ according to the country. Apprentices are less often hired by their training company upon graduation in France than in Germany. However, contrary to Germany, non-retained French graduates still benefit from the good signal apprenticeships have on the external labour market. Value of the control variables given, they indeed spend less time unemployed than school leavers which is not the case in Germany.

Causality is ensured via an instrumental variable strategy where the instrument is the proportion of apprentices in the total number of pupils or students at the relevant level prevailing in the year preceding the choice of stream. Upon graduation of secondary education, I find that apprenticeship training benefit students in difficulty (the compliers) in terms of avoiding unemployment in France but not in Germany. As for wages, the impact is null in both countries. Finally, for graduates from higher education, the transition via an apprenticeship does not help integration, in both France and Germany.

To increase its stock of apprentices per the German model, French governments have taken three main avenues: (i) they opened the track to higher education in the late 1980s; (ii) they launched advertising campaigns oriented towards employers, families and the youth; (iii) they decreased the labour cost of apprentices.

The third chapter, entitled The impact of apprenticeship cost on firms’ propensity to train and on mobility upon graduation, focuses on the latter avenue. It analyses the impact of subsidies offered to employers of apprentices on firms’ likelihood to train and on retention rates in the training firms upon graduation. The identification strategy is based on the regionalization of a large subsidy offered to employers of apprentices, the indemnité compensatrice forfaitaire (ICF). The law was put into force in 2005. At the time, the ICF accounted for about a quarter of all public money spent on apprenticeship training. By then, regions could decide upon the criteria of the ICF and the amounts associated, which generated large exploitable variations in the cost of apprenticeships. These variations are used to explain: (i) the average regional dynamic of the number of apprentices taken on in each firm over time; (ii) the regional retention rates.

Data comes from four different sources. First, information on all ICF reforms in 16 of the 22 French metropolitan regions was gathered from the regional services for apprenticeship. This new database necessitated many inquiries and took about a year to be constituted. Second, the administrative database Ari@ne brings information on more than 80% of all apprenticeship contracts signed in France on the period of interest. It provides knowledge on both firms and apprentices at the time when contracts are signed. Third, the administrative database DADS gives account of working contracts of all wage earners employed in the private sector, to the exception of private individuals’ employees before 2009. Fourth, the administrative database FICUS-FARE brings yearly information on active firms in the country. Combining these sources of data makes it possible to compute the average hourly cost for about 145 000 contracts signed each year between 2000 and 2012.

Using linear regressions with firm fixed effects, I show that subsidies foster turnover strategies. Thus, I find a limited but significantly negative elasticity of the number of apprentices hired to training costs. The point estimate is -0.22. The impact however mostly plays at the intensive margin (training firms taking on more apprentices) rather than at the extensive margin (new firms entering the system). This suggests that training firms may respond to subsidies by training over their needs in skills. Confirming this interpretation, I find that the elasticity of mobility upon graduation to training cost is negative and equal to -0.40.

The literature in education research has shown that the least academically inclined students are the ones benefitting the most from work-based learning methods. A positive impact of the development of apprenticeship training on the labour market outcomes of this population should therefore be a prior to foster apprenticeships. The second chapter has shown that, on the massive market of apprenticeships in Germany, the track does not benefit least achievers because of both their low likelihood to be retained upon graduation and the low value of their training on the external labour market. On the smaller market of apprenticeship training in France, the track eases the integration of the population of interest which urges to increase the stock of apprentices. Yet, the low level of employers’ coordination inherited from the liberal laws following the 1789 Revolution has made it difficult for economic actors to head this development. The State therefore steps in via subsidies addressed to employers which, the third chapter has shown, has a slightly positive impact on the number of contracts signed with a detrimental effect on retention rates.

Put together, and bringing generality to the results, these conclusions suggest that there is a tipping point after which the development of apprenticeship training brings too much competition at entrance and exit of the system for the least achievers. In particular, their likelihood to be retained in their training firm upon graduation becomes too small. As a result, development of apprenticeship training via subsidies on the small apprenticeship markets may gain to be led in combination with policies ensuring strong retention rates. A good way to achieve this could be to give works councils large information and co-determination rights on the matter. Kriechel, Muehlemann, Pfeifer, & Schütte (2014) indeed showed that such policy has a positive impact on retention rates in the German case.

Table of contents :

General introduction

Introduction générale

Chapter 1 The impact of works council membership on wages in Germany: a case of strategic discrimination?

Abstract

Introduction

1 The economic literature

2 The institutional context

3 Data

4 Descriptive statistics

5 Estimations

6 How to explain the results

Conclusion

Appendix

Chapter 2 Apprenticeship training, better labour market outcomes in France than in Germany

Abstract

Introduction

1 Apprenticeship and insertion: institutional models and pre-existent literature

2 Data and identification strategy by instrumental variables

3 Descriptive statistics

4 Apprenticeship training, better labour market outcomes in France than in Germany on the short run

5 Most impacts are persistent on the medium run

Conclusion

Appendix

Chapter 3 The impact of apprenticeship cost on firms’ propensity to train and on mobility upon graduation

Abstract

Introduction

1 The literature

2 A simple theoretical framework

3 The ICF and the cost of apprenticeship training

4 Data

5 Descriptive statistics

6 The results

Conclusion

Appendix

Main conclusion

Conclusion générale

Bibliography