Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Status of carbon markets

In Kenya, Njiru (2011) notes that Mumias Sugar Company, a major player in the agricultural sector, is already engaged in voluntary carbon trading through an Emissions Reduction Purchase Agreement entered into by the World Bank and Japan Carbon Finance. Many other entities are in the process of establishing projects or redesigning existing projects and business processes so as to be able to generate CERs and take advantage of the carbon market (Njiru 2011). This will not only help entities to reduce their carbon footprint, but also facilitate the creation of an additional revenue stream.

The GRK (2012:3), through the Ministry of Finance, has prepared a national policy on carbon finance and emissions trading. This policy is expected to guide the setting up of a regulatory and institutional framework for developing and managing carbon trading in Kenya. The policy aims to create a carbon trade sector which will tap into international climate change finances, support sustainable development programmes, provide employment and economic diversification, increase access to innovative research and technology, improve Kenya’s balance of payments, and foster the involvement of the private sector in carbon investment and trading (GRK 2012:4). The agricultural sector, which is the main stay of the economy, is expected to be the largest beneficiary of the initiatives being undertaken by the government (GRK 2012.5).

The carbon market has not been without challenges so far. The reduced industrial activity during the economic downturn occasioned an over-supply of allowances because many companies were unable to meet their operational targets (McGregor 2014). This over-supply of allowances resulted in market uncertainty, sending the carbon price sliding significantly and removing the incentive for polluters to cut their emissions (Forest Trends 2015:12).

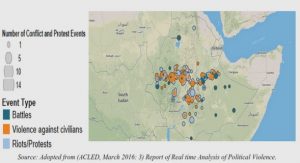

Additionally, the compliance carbon market suffered a huge setback after the expiry of the first binding period of the Kyoto Protocol, without any binding accord following the failure of Copenhagen COP 15 negotiations (McGregor 2014). The setback also affected the voluntary carbon market resulting in prices being depressed (Forest Trends 2015:13). However, according to Forest Trends (2015:15) the market remained resilient to recording increased volumes, as depicted in figure 1.2. Although short-term ‘back loading’ measures to reduce the number of allowances in the market were unsuccessful, the carbon market is currently going through structural reform (Forest Trends 2015:12). These structural reforms are expected to enhance the credibility of the carbon market and provide cost-effective ways to achieve emissions reductions (Forest Trends 2015:12). The structural reforms explain why many countries and economic blocks are in the process of establishing emissions trading schemes which will further stimulate low carbon investment, particularly in the agricultural sector.

SUSTAINABILITY REPORTING

Investors, regulators and an expanding array of other stakeholders are increasingly interested in entities’ financial and non-financial information, particularly about their sustainability initiatives. According to White (2009), an entity’s commitment to sustainability necessitates the need for greater transparency in the disclosures of entity strategy, performance drivers and the management philosophies and briefs about shared social and environmental welfare. However, according to Herremans, Nazari and Ingraham (2012:28), regulatory, normative, and cognitive pressures result in differing rigour in the processes of sustainability reporting, namely:

structuring responsibility for the report;

gathering data and assuring its accuracy; and

linking sustainability reporting to society’s needs and expectations (Herremans et al. 2012:28).

White (2009) indicate that sustainability reporting involves disclosing both the non-financial and the financial indicators of an entity’s impact on the environmental, economic and social dimensions of their operations, which is crucial in driving interest and investment in sustainability to the mutual benefit of both entities and investors. According to White (2009), environmental and sustainability reporting address the stakeholders’ demand for more transparency and accountability in management’s actions and decisions.

Accounting for sustainability involves evaluating risks and opportunities so as to link sustainability initiatives to the entity’s strategy (White 2009). Furthermore, entities can improve their sustainability performance by measuring, monitoring and reporting information that is useful for decision-making. Such measurement and disclosures will in turn ensure that the sustainability initiative enhances its positive impact on society and the environment, thus leading to a more sustainable future. Elliott and Elliott (2012:847) argued that the growth in voluntary sustainability reporting is in response to market and political pressures.

Consequently, the trend in voluntary sustainability reporting has been spontaneous with no clear guidelines. This spontaneous growth in sustainability reporting has resulted in information that is impossible to analyse or compare which significantly impairs judgment when it comes to decision-making.

The agricultural sector, which, according to Maina and Wingard (2013), is largely perceived as a cultural practice, has not shown any trend in sustainability reporting. According to Ernst and Young (2009), traces of information about sustainability activities are scattered in an uncoordinated manner in the financial statements. Moreover, the lack of sector-specific guidelines leaves some room for the preparers of financial statements to highlight the favourable information only, omitting facts on negative impacts.

Content of sustainability reports

Deloitte (2009) indicates that reported information should identify and explain the connection between the entity’s strategic objectives, the industry, the market and the social context within which the business operates. Equally important is the associated risks and opportunities, the key resources and relationships, and the governance structures established by management to ensure that the sustainability objectives are achieved. Further, such information should explain the connection between the business’s strategy and the financial and non-financial performance. Ernst and Young (2009) argues that, if due consideration is made in preparing annual reports, sustainability reporting should not create any significant additional administrative burden, and may indeed create net benefits by helping to recognise and reduce compliance obligation.

Chapter 1 Introduction

1.1 Background information

1.2 The withdrawal of IFRIC 3 .

1.3 Problem statement .

1.4 Points of departure and assumptions

1.5 Research objectives

1.6 Description of the research methods that were used

1.7 Research subjects .

1.8 Where the research was conducted

1.9 The research’s contribution to the subject

1.10 Research structure

Chapter 2 Sustainability reporting in the agricultural sector

2.1 Introduction

2.2 The concept of sustainabilit

2.3 Sustainability activities in the agricultural sector

2.4 Mechanisms and operation of carbon markets .

2.5 Sustainability reporting

2.6 Sustainability accounting theories

2.7 Theoretical framework of the study

2.8 Problems in implementing sustainability accounting theor

Chapter 3 Classification and measurement for cap-and-trade schemes on initial recognition

3.1 Introduction

3.2 Sustainable agricultural land management (SALM)

3.3 Initial recognition issues

3.4 Initial classification

3.5 Measurement on initial recognition

3.6 Measurement uncertainty

3.7 The derivative instruments relating to cap-and-trade schemes

3.8 Summary and conclusions

Chapter 4 Valuation of assets used in cap-and-trade schemes

4.1 Introduction

4.2 Subsequent measurement

4.3 Provision of accounting standards

4.4 Subsequent measurement and valuation

4.5 Valuation model for biological assets involved in cap-and-trade schemes

4.6 Market illiquidity

4.7 Influence of preparers of financial statements

4.8 Summary and conclusion

Chapter 5 Reporting for cap-and-trade scheme

5.1 Introduction .

5.2 Trends in reporting for cap-and-trade activities

5.3 Mandatory disclosures

5.4 Voluntary disclosures

5.5 Quantitative disclosures

5.6 Qualitative disclosures ..

5.7 Integrated reporting

5.8 Key challenges in accounting for cap-and-trade schemes .

5.9 Summary and conclusions

Chapter 6 Research design

Chapter 7 Data analysis, presentation and interpretation

Chapter 8 Summary, conclusions and recommendations

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT

Recognition, measurement and reporting for cap-and-trade schemes in the agricultural sector