Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Chapter 2 Defining Information Inequality and Poverty

Introduction

Information inequality and poverty are complex and multi-faceted phenomena that affect millions of people throughout the world. This study explored these concepts within the context of information and knowledge societies to better understand their nature and how libraries might work to alleviate them in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and other developing communities. Over the last few decades, information has become the basis of the global economy. It is a form of capital, a commodity of which ownership and access is imperative to living a life of fulfillment and dignity (UNESCO, 2005). This research is not only focused on information but the broader, deeper concept of knowledge is also incorporated. The differences between information and knowledge will be discussed in this chapter and the layered manifestations of information inequality and poverty will be explored. For instance, individuals and communities are said to be information poor when they lack the abilities to access information and knowledge considered vital to survival and growth. But information inequality and poverty are more than just the lack of physical or technological access to information. Also important in the discussion are the skills people need to find, share, create, and effectively utilise information and knowledge. In addition, the relevance of information and knowledge and its presentation to those in developing communities must be clear and meaningful. In information and knowledge societies, the success of an individual or community can hinge upon attaining needed information and knowledge and as this dependence upon information grows, so does the gap between those who have this ability and those who do not. Because millions of global citizens do not have the access or skills to locate and use relevant information to better their conditions, the number of those living in information inequality and poverty continues to grow. This information inequality and poverty that will be explored in this thesis. In order to accomplish this, first the concepts of the information society and knowledge societies will be explored in this chapter and their characteristics explained. The differences between information and knowledge will be defined. Information inequality will be discussed in more depth and a definition and explanation of information poverty provided. Causes and characteristics of information inequality and poverty will be investigated so that a complete understanding will be attained before moving to Chapter 3’s discussion of public libraries in South Africa and the ways in which information inequality and poverty and these libraries are connected.

Understanding the information and knowledge era and information and knowledge societies

There have always been people in the world who have suffered due to a lack of information and knowledge. They may not have realised it or called it information inequality or poverty but lacking relevant, useful information and knowledge for problem-solving, education, employment or other goal-attainment has always been present. What makes information inequality and poverty in this era more distinctive and worth studying? What makes them problems of vital importance to address?

While some have argued that the sheer volume of information now being produced has increased, I am of the opinion that it is more that the accessibility of information has increased, especially digitally, and that the dominant ways to access and use that information have been significantly altered with the increase in ICTs around the world. In this view, I am influenced by Hudson’s (2012) critical exploration of the discourse LIS uses to discuss information and knowledge in the current era and will depend on it as a guiding framework. Hudson (2012) is skeptical that the amount of information in the world has increased; instead, he uses critical development theories to explore how we speak about information and knowledge, which uncovers important lessons regarding access to information, how we evaluate it, and the value we place upon different types. I agree with Webster (2006:9) that the “character of information” has changed and has “transformed how we live.” In addition, there are deep cultural, social, political, and moral layers to information; it is not only just “information” now but “knowledge” that is important in the alleviation of information inequality and poverty. As mentioned in Chapter 1, Hudson (2012) warns against adhering to the dominant Western paradigm unilaterally. Viewed through that perspective alone, the value and validity of indigenous ways of knowing and communicating are undermined in the information and knowledge era. Taken a step further, this paradigm assigns more value to technology in knowledge access, production, and transmission, thus effectively forcing more traditional societies into a state of information inequality and poverty that may or may not be appropriate. With Hudson’s (2012) critical perspective in mind, I will continue the thesis with an explanation of the common (dominant) terminology used in information and knowledge era and society research. In doing so, I hope to provide some clarity to discussions which often confuse or interchangeably use these terms and explain how I have chosen to use the terms in this thesis.

The terms information era and information society have been used most often to describe the current state of the world since the explosion of information technology caused the society based on industry to transition to one based on information and knowledge (Zaaiman, 1985; Nassimbeni, 1998; International Telecommunication Union (ITU), 2005, 2014; Mansell, 2010; Pantserev, 2010; Lesame, 2013). During the course of this research, I found that often the terms were used interchangeably. This can be both confusing and misleading, especially in the common practice of using information society to refer to the information era because, as will be shown, not all societies in this era have achieved information society status. It is clear now that while all societies are situated within the current information era, not all societies can be considered information societies. Thankfully, the use of these terms is changing now in at least two ways. First, the two terms are becoming less synonymous with one another. Information era now more clearly refers to the time frame in which we currently live, the characteristics of which will be described in more detail later in this chapter. Information society (or societies) refers to specific countries, communities, or other aggregates of people living together, specifically with reference to the fulfillment of the “qualifications” required of such a society, which will also be explained further later in this thesis. Second, these terms are more often adding or exchanging the term knowledge for information. As research in these areas has evolved, it has wisely begun to incorporate existing distinctions between information and knowledge into the work and definitions.

The difference between information and knowledge is important in this context, as is the choice to use the plural form of society. “Knowledge requires interpretation by human beings” (Mansell, 2013:5); it occurs when information is organised, structured, or patterned and when meaning is otherwise imposed upon it by humans. The plural form of society is used because, as UNESCO (2005) argues, it would be impossible to narrow down these diverse dimensions into a singular overarching society. Information and knowledge societies in the information and knowledge era have an increased focus on human rights, preservation of linguistic and cultural diversity, freedom of expression and education, knowledge-sharing, awareness of global issues, and community participation than those of the past (UNESCO, 2005). Knowledge can be used to fight poverty and injustice as long as citizens are equipped with the capacities to use it critically (UNESCO, 2005) but also only when systems of power are critically investigated and disrupted in favor of more equitable, inclusive models. These themes will be investigated further throughout this thesis.

This thesis will use the term information and knowledge era to describe the current era in which we live. It will use the term information and knowledge society (or societies) to refer to those societies that have fulfilled the requirements of an information and knowledge society explained later in this chapter. In order to gain a fuller understanding of these terms, more explanation is now provided first of the information and knowledge era and then of information and knowledge societies.

The information and knowledge era

The information and knowledge era has also been referred to as the information economy (Warschauer, 2003; Swanson, 2004), the knowledge economy (Norris, 2001), the internet age (Norris, 2001), the network society (Castells, 2010; Webster, 2006), and even the third industrial revolution (Warschauer, 2003; UNESCO, 2005). This era has also recently been referred to as the Age of Intelligence, especially in conversations regarding the Internet of Things (Shaffer, 2014)10. To trace the full evolution of the information and knowledge era is beyond the scope of this thesis but a brief synopsis will be given here to provide related background helpful to understanding information inequality and poverty.11 “The information and knowledge society has been brought about by the transformation and evolution of previous societies and the use of tools for development (e.g. the Stone Age, Bronze Age, the Industrial Revolution)” (Jiyane et al., 2013:1-2).12 The world economy that was once driven by industry and production has evolved into one, with the rapid development of information and communication technologies (ICTs), in which information is treated as a commodity, as a form of capital (UNESCO, 2005). While people have always needed information, it is often said that the current era differs because the creation of information is faster and easier for many and thus there is more information through which to navigate (UNESCO, 2005). Lesame (2013:76) points to the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) held in Tunis in 2005 as “the end of the Industrial Era and the beginning of the Information Age.” Essentially, information has replaced production as the defining character of the industrial society (Lesame, 2013:76). In this era, information technology is often needed for access to the most current information, so communities must have the infrastructure to support ICTs and global citizens need the skills to use them. Access to information or the lack thereof will, in large part, determine a community’s or individual’s participation in political, social, and economic processes. This helps determine a community’s information and knowledge society status in the information and knowledge era. Many wealthier, developed nations have been able to harness the power of information to their advantage, often to the detriment of developing countries. Because of this trend, a gap between those who could participate in the information and knowledge era and those who could not continued to grow and the resulting inequality of information continues to have devastating global effects.

DECLARATION

ETHICS STATEMENT

SUMMARY

ABSTRACT

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

DEDICATION

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF APPENDICES

LIST OF TABLES

LIST OF FIGURES .

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

CHAPTER ONE BACKGROUND TO THE STUDY

1.1. Introduction

1.2. Background

1.3. Study setting

1.3.2. KwaZulu-Natal

1.3.2.1. Public libraries in KwaZulu-Natal

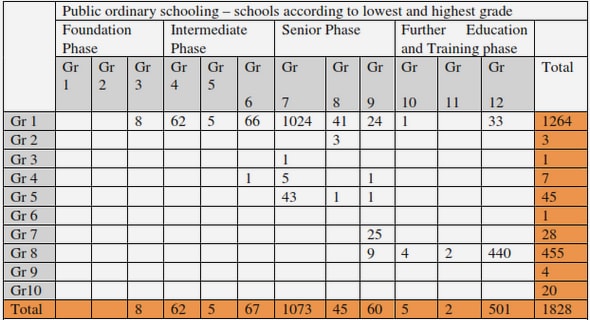

1.3.2.2. Schools in KwaZulu-Natal

1.4. Statement of the problem

1.5. Purpose and objectives

1.6. Research question

1.7. Literature review

1.7.1. Literature on libraries and librarians in Africa and South Africa

1.7.2. Literature on the information society, knowledge society, and LIS

1.7.3. Literature on information and communication technologies and the digital divide

1.7.4. Literature on information inequality and information poverty

1.7.5. Literature on social justice and information access

1.7.6. Literature on library initiatives related to information access and inequality in developing areas

1.7.7. Reports and surveys

1.7.8. Limitations of existing research

1.8. Introduction to the theoretical framework of the study .

1.9. Introduction to the research design and methodology of the study

1.10. Significance of the study and its contribution to library and information science

1.12. Structure of this thesis .

CHAPTER 2 DEFINING INFORMATION INEQUALITY AND POVERTY

2.1. Introduction .

2.2. Understanding the information and knowledge era and information and knowledge societies.

2.2.1. The information and knowledge era

2.2.2. Information and knowledge societies .

2.3. Information inequality defined

2.4. Information poverty defined.

2.5.1 Lack of connectivity

2.5.2 Lack of quality information

2.5.3 Inability to benefit from information

2.6. Characteristics of information inequality and poverty

2.6.1. Information inequality and poverty are complex and multi-faceted

2.6.3. Information inequality and poverty discourage participation in a democratic society

2.6.4. Information Inequality and Poverty are Connected to Economic Poverty .

2.6.5. Information inequality and poverty are social justice issues

2.6.6. Assessment of information inequality and poverty is challenging but Necessary

2.7. Approaches to information inequality and poverty

2.7.1. Information technology/Infrastructural approach

2.7.2. Content/Access approach

2.7.3. Hermeneutical/Understanding approach

2.7.4. Britz’s approach

2.7.5. Childers’ and Post’s tripartite culture of poverty model .

2.7.6. Chatman’s small world approach.

2.7.7. Thompson’s information access model

2.8. Conclusion

CHAPTER 3 THE DEVELOPMENT OF SOUTH AFRICAN PUBLIC LIBRARIES AND THEIR ROLE IN INFORMATION INEQUALITY AND POVERTY .

3.1. Introduction

3.3. Libraries in apartheid South Africa

3.4. Libraries in post-apartheid South Africa

3.5. Themes characterising South African library development

3.6. Conclusion

CHAPTER 4 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK OF THE STUDY

4.1. Introduction

4.2. Theoretical underpinning of study .

4.3. An integrative approach to information inequality and poverty

4.4. Conclusion

CHAPTER 5 RESEARCH DESIGN

5.1. Introduction

5.2. Research paradigms

5.3. Research methodologies

5.4. Traditions (strategies) of inquiry

5.5. Case study setting

5.6. Participant selection

5.7. Data Collection Methods

5.8. Data collection procedures

5.9. Validity, reliability, and generalisability1

5.10. Data analysis

5.11. Ethical considerations

5.12. Conclusion

CHAPTER 6 DATA ANALYSIS AND PRESENTATION OF FINDINGS

6.1. Introduction

6.2. The findings

6.3. Conclusion

CHAPTER 7 INTERPRETATION OF FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

7.1. Introduction

7.2. Applying the integrative approach to information inequality and poverty

7.3. Analysis of the findings of this study

7.4 Recommendations for libraries in the alleviation of information inequality and poverty

7.5. Conclusions

CHAPTER 8. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

8.1. Introduction

8.2. Conclusions

8.3. Overall conclusions of the research problem

8.4. Suggestions for Further Study

REFERENCES

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT