Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

CHAPTER 2 Electrochemistry: An Overview

Basic concepts

Electrochemistry, as the name suggests, studies the relationship between electrical and chemical occurrences.1It covers mainly two areas: electrolysis-conversion of chemical compounds by passage of an electric current and electrochemical power sources-energy of chemical reactions transformed into electricity. Electrochemistry is one effective technique to study electron transfer properties. When electron transfer is between a solid substrate and a solution species, it is termed heterogeneous process. Inversely, if electron transfer reaction occurs between two species, both of which are in solution, the reaction is homogeneous. Therefore, electrochemistry can specifically be defined as the science of structures and processes at and through the interface between an electronic (electrode) and an ionic conductor (electrolyte) or between two ionic conductors.2

Electrochemistry is an interdisciplinary science that is mainly rooted in chemistry and physics; however, also linked to engineering and biochemistry/biology. Due to its diversity, electrochemistry has found application in various working fields such as: analytical electrochemistry; environmental electrochemistry;3 electrochemistry of glasses;4 ionic liquids electrochemistry; microelectrochemistry,nanoelectrochemistry; photoelectrochemistry;3solid state electrochemistry; solution electrochemistry; surface electrochemistry;technical electrochemistry with numerous subtopics such as: Batteries and energy storage5; Corrosion and corrosion inhibition; Electrochemical synthesis and reactors (electrosynthesis); Electronic components (capacitors, displays, information storage, rectifiers); Fuel cells and galvanic deposition; Theoretical or quantum electrochemistry.Electrochemistry also involves the measurement of potential (potentiometry) or current response (voltammetry).6 The work described in this dissertation involves current measurement,voltammetry and a number of voltammetric techniques, namely, cyclic voltammetry (CV), linear sweep voltammetry (LSV), square wave voltammetry (SWV), chronoamperometry (CA) and chronocoulometry.

The electrode-solution interface

The interface between a metal (electrode) and an electrolyte solution is considered when trying to gain an impression of the structures and processes that occur in electrochemical systems. Figure2.1 shows a schematic diagram of the interface structure and the processes. This interface is generally charged; the metal surface carries an excess charge, which is balanced by a charge of equal magnitude and opposite sign on the solution side of the interface. The resulting charge distribution; two narrow regions of equal and opposite charge, is known as the electric double layer. It can be viewed as a capacitor with an extremely small effective plate separation, and therefore has a very high capacitance.

Reactions involving charge transfer through the interface, and hence the flow of a current, are called electrochemical reactions. Two types of such reactions can occur at the interface. One is an instance of metal deposition. It involves the transfer of a metal ion from the solution onto the metal surface, where it is discharged by taking up electrons. Metal deposition takes place at specific sites. The deposited metal ion may belong to the same species as those on the metal electrode, as in the deposition of a Ag+ion on a silver electrode, or it can be different as in the deposition of a Ag+ ion on platinum. In any case the reaction is formally written as:

Ag+(solution) + e- (metal) Ag(metal) (2.1)Metal deposition is an example of a more general class of electrochemical reactions, ion transfer reactions. In these an ion, e.g. a proton or a halide ion, is transferred from the solution to the electrode surface, where it is subsequently discharged.Another type of electrochemical reaction, is an electron-transfer reaction, an oxidized species is reduced by taking up an electron from the metal. Since electrons are very light particles, they can tunnel over a distance of 10 Å or more, and the reacting species need not be in contact with the metal surface. The oxidized and the reduced forms of the reactants can be either ions or uncharged species. A typical example for an electron-transfer reaction is:

Fe3+(solution) + e- Fe (metal) Fe2+(metal) 3+(solution) + e- (metal) Fe2+(metal) (2.2)Both ion and electron transfer reactions entail the transfer of charge through the interface, which can be measured as the electric current. Based on the definition of the electric double layer, Helmholtz7proposed a simple geometric model of the interface. This model gave rise to the concept of the inner and outer Helmholtz planes (layers).The inner Helmholtz layer comprises all species that are specifically adsorbed on the electrode surface. If only one type of molecule or ion is adsorbed, and they all sit in equivalent positions, then their centres define the inner Helmholtz plane (IHP). The outer Helmholtz layer

comprises the ions that are closest to the electrode surface, but are not specifically adsorbed. They have kept their solvation spheres intact,and are bound only by electrostatic forces. If all these ions are equivalent, their centres define the outer Helmholtz plane (OHP). The layer which extends from the OHP into the bulk solution is a three dimensional region of scattered ions called the diffuse or Gouy layer.The IHP and OHP represent the layer of charges which is strongly held by the electrode and can survive even when the electrode is pulled out of the solution.

Faradaic and non-Faradaic processes

Faraday’s law states that the number of moles of a substance produced or consumed during an electrode process, is proportional to the electric charge passed through the electrode; Redox processes are often governed by this law. Electron transfer reactions proceeding at the charged interface obeying this law are called Faradaic process.Non-Faradaic process arise when an electrode-solution interface shows a range of potentials where no charge-transfer reactions occur.However, processes such as adsorption and desorption can occur, and the structure of the electrode-solution interface can change with changing potential or solution composition. Although charge does not cross the interface, external currents can flow (at least transiently) when the potential, electrode area, or solution composition changes.

Mass transport processes

The movement of charged or neutral species that allows the flow of electricity through an electrolyte solution in an electrochemical cell is referred to as a mass transport process. Migration, diffusion and convection are the three possible mass transport processes accompanying an electrode reaction.Migration: Migration is the movement of charged particles along an electrical field; this charge is carried through the solution by ions. To limit migrational transport of the ions that are components of the redox system examined in the cell, excess supporting electrolyte is added to the solution; in this work a large concentration of KCl is used. In analytical applications, the presence of a high concentration of supporting electrolyte which is hundred times higher than the concentration of electroactive ions means that the contribution of examined ions to the migrational transport is less than one percent.Then it can be assumed that the transport of the examined species towards the working electrode is by diffusion only. Migration of electroactive species can either enhance or diminish the current flowing at the electrode during reduction or oxidation of cations. It helps reduce the electrical field by increasing the solution conductivity, and serves to decrease or eliminate sample matrix effects. The supporting electrolyte ensures that the double layer remains thin with respect to the diffusion layer, and it establishes a uniform ionic strength throughout the solution. However, measuring the current under mixed migration-diffusion conditions may be advantageous in particular electrochemical and electroanalytical situations.1 Uncharged molecules do not migrate.

Diffusion: Diffusion is the transport of particles as a result of local difference in the chemical potential.10 Diffusion is simply the movement of material from a high concentration region of the solution to a low concentration region. Electrochemical reactions are heterogeneous and hence they are frequently controlled by diffusion. If the potential at an electrode oxidizes or reduces the analyte, its concentration at the electrode surface will be lowered, and therefore, more analyte moves to the electrode from the bulk of the solution, which makes it the main current-limiting factor in voltammetric process. Although migration carries the current in the bulk solution during electrolysis, diffusion should also be considered because, as the reagent is consumed or the product is formed at the electrode, concentration gradient between the vicinity of the electrodes and the electroactive species arise. Indeed,under some circumstances, the flux of electroactive species to the electrode is due almost completely to diffusion.

Convection: Convection is one of the modes of mass transport which involves the movement of the whole solution carrying the charged particles. The major driving force for convection is an external mechanical energy associated with stirring or flow of the solution or rotating or vibrating the electrode (forced convection). Convection can also occur naturally as a result of density gradient.11 In voltammetry,convection is eliminated by maintaining the cell under quiet and stable condition.

Voltammetry

Voltammetry is the measurement of current as a function of a controlled electrode potential and time. The resultant current–voltage(or current–time or current–voltage–time) display is commonly referred to as the “voltammogram”.1,12 The term “voltammetry” was coined by Laitinen and Kolthoff.13,14 The objectives of a voltammetric experiment also vary, ranging from analytical measurements designed to determine the concentration of an analyte to measurements designed to elucidate complex mechanisms and the values of the associated thermodynamic and kinetic parameters.1 The protocol for potential control may vary, leading to a number of different techniques each with their common names. The techniques used in this work are cyclic voltammetry (CV), linear sweep voltammetry (LSV), square wave voltammetry (SWV), chronoamperometry (CA) and chronocoulometry.This section gives the basic theoreticalbackground underlying thesentechniques.

Cyclic voltammetry

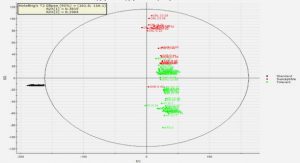

This is a commonly employed type of voltammetry where measurement of the current response of an electrode to a linearly increasing and decreasing potential cycle is performed.15 Figure 2.2 presents the resulting scan of potential against time, scanning linearly the potential of a stationary working electrode in an unstirred solution,using a triangular potential waveform and the corresponding voltammogram. The experiment is usually started at a potential where no electrode process occurs (0.2 V in the plot) and the potential is scanned with a fixed scan rate to the switching potential (0.7 V in the plot). When an electrochemically active compound is present in the solution phase, an anodic current peak at the potential Epa is detected with the peak current Ipa. When the potential is swept back during the reverse scan a further current peak at the potential Epc may be observed with a cathodic peak current Ipc.

DEDICATION

DECLARATION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABSTRACT

Table of Contents

Abbreviations

List of Symbols

List of Schemes

List of Tables

List of Figures

CHAPTER 1 General Overview of Dissertation

1.1 Background of Project

1.1.1 Introduction

1.1.2 Aim

1.1.3 Objectives

1.1.4 Scientific novelty of the work

1.1.5 Publication of the work

1.1.6 Structure of the thesis

References

SECTION A

CHAPTER 2

Introduction

2.1 Electrochemistry: An Overview

2.1.1. Basic concepts

2.1.1.1. The electrode-solution interface

2.1.1.2. Faradaic and non-Faradaic processes

2.1.1.3. Mass transport processes

2.1.2. Voltammetry

2.1.2.1. Cyclic voltammetry

1.1.2.1.1. Reversibility

1.1.2.1.2. Irreversibility

1.1.2.1.3. Quasi-reversibility

2.1.2.2. Linear sweep voltammetry

2.1.2.3. Square wave voltammetry

2.1.2.4. Chronoamperometry

2.1.2.5. Chronocoulometry

2.1.3. Electrocatalysis

2.1.4. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy

2.1.4.1. Data Presentation

2.1.4.2. Data Interpretation

2.1.4.3. Validation of Measurement

2.2 Chemically Modified Electrodes

2.2.1. General Methods of Modifying Electrode Surfaces

2.2.1.1. Chemisorption

2.2.1.2. Covalent Bonding

2.2.1.3. Composite

2.2.1.4. Coating by thin films

2.3 Carbon Electrodes

2.3.1. Diamond Electrode

2.3.2. Graphite Electrode

2.4 Carbon Nanotubes: General Introduction

2.4.1. Historical Perspective

2.4.2. Structure of Carbon Nanotubes

2.4.3. Synthesis of Carbon Nanotubes

2.4.4. General Applications of Carbon Nanotubes

2.5 Metallophthalocyanines: General Introduction

2.5.1. Historical Perspective

2.5.2. Structure of Metallophthalocyanines

2.5.3. Synthesis of Metallophthalocyanines

2.5.4. Electronic Absorption Spectra of Metallophthalocyanines .

2.5.5. Electrochemical Properties of Metallophthalocyanines

2.5.5.1. Ring Process

2.5.5.2. Metal Process

2.5.6. General Applications of Metallophthalocyanines

2.6 Overview of Target Analytes

2.6.1. Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR)

2.6.2. Formic Acid Oxidation

2.6.3. Thiocyanate Oxidation

2.6.4. Nitrite Oxidation

2.7 Microscopic and Spectroscopic Techniques

2.7.1. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

2.7.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.7.3. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.7.4. Energy Dispersive X- Ray Spectroscopy (EDS)

2.7.5. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

References

CHAPTER 3 Experimental

3.1 Introduction

3.1.1. Reagents and Materials

3.1.2. Synthesis

3.1.2.1. Synthesis of Nanostructured Iron(II) and Cobalt(II) Phthalocyanines

3.1.2.2. Synthesis of Iron(II) and Cobalt(II) Octabutylsulphonylphthalocyanines

3.1.2.3. Synthesis of Iron(II) tetrakis(diaquaplatinum) octacarboxyphthalocyanine (C40H24N8FeO24Pt4)

3.1.3. Purification of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes

3.1.4. Electrode Modification Procedure

3.1.5. Electrochemical Procedure and Instrumentation

References

SECTION B RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

CHAPTER 4 Microscopic,Spectroscopic,Electrochemical,and Electrocatalytic Properties of Nanostructured Iron(II) and Cobalt(II) Phthalocyanine

4.1 Microscopic and Spectroscopic Characterisation

4.1.1. Comparative SEM, AFM and EDX

4.2 Electrochemical Characterisation

4.2.1. Electron transfer behaviour: cyclic voltammetry

4.2.2. Diffusion Domain Approximation Theory

4.2.3. Electron transport behaviour: Impedimetric characterization

4.3 Electrocatalytic Properties

4.3.1. Electrocatalytic reduction of oxygen

4.3.2. Electrocatalytic oxidation of thiocyanate

4.3.3. Electrocatalytic oxidation of nitrite

References

CHAPTER 5 Microscopic,Spectroscopic,Electrochemical,and Electrocatalytic Properties of Iron(II) and Cobalt(II) Octabutylsulphonylphthalocyanine

5.1 Microscopic and Spectroscopic Characterisation

5.1.1. SEM characterisation

5.1.2. Characterization using UV-visible Spectrophotometer

5.2 Electrochemical Characterisation

5.2.1. Solution Electrochemistry

5.2.2. Electron transfer behaviour: cyclic voltammetry

5.2.3. Electron transfer behaviour: impedimetric characterisation

5.3 Electrocatalytic Properties

5.3.1. Electrocatalytic reduction of oxygen

5.3.1.1. Effect of scan rates

5.3.1.2. Chronocoulometric studies

5.3.1.3. Hydrodynamic voltammetry investigation

5.3.2. Electrocatalytic oxidation of thiocyanate

5.3.3. Electrocatalytic oxidation of nitrite

References

CHAPTER 6 Microscopic,Spectroscopic,Electrochemical,and Electrocatalytic Properties of Iron(II) tetrakis(diaquaplatinum)octa-carboxy phthalocyanine

6.1. Microscopic and Spectroscopic Characterisation Microscopic and spectroscopic information of iron

6.1.1. UV-visible characterisation

6.1.2. Elemental analysis and mass spectroscopy characterisation

6.1.3. XRD and EDX Characterisation

6.1.4. Comparative SEM and TEM characterisation

6.2. Electrochemical Properties

6.2.1. Solution electrochemistry

6.2.2. Electron transfer behaviour: cyclic voltammetry

6.2.3. Electron transfer behaviour: Impedimetric characterisation

6.3 Electrocatalytic Properties

6.3.1. Electrocatalytic reduction of oxygen

6.3.2. Electrocatalytic oxidation of formic acid

6.3.2.1. Comparative cyclic voltammetric response

6.3.2.2. Chronoamperometry experiment

6.3.2.3. Concentration studies: Tafel analysis

6.3.2.4. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy experiments

6.3.2.5. Tolerance to carbon monoxide poisoning.

References

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

CONCLUSIONS

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

APPENDIX A

List of scientific publications

APPENDIX B

List of scientific conferences