Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Theoretical Background

This section will review existing literature and theories relating to the purpose of this research. It starts with a discussion about Conspicuous Consumption and the importance of Costly Signaling. Following a frame-work is presented determining which aspects comprise the reliability of a signal. After that the identified as-pects are elaborated. Finally, the importance of Generation Y for today’s luxury marketing will be dis-cussed

Conspicuous Consumption

Consumption – defined as spending money to acquire goods and services – is instrumental to satisfy a person’s needs and wants. The extent to which a product can serve that purpose depends on its properties (Witt, 2010). These properties might depend on a product’s func-tional characteristics. Yet, a number of consumer research studies support the premise that individuals look beyond the basic functional utility of a product (Berger & Heath, 2007; Chaudhuri & Majumdar, 2006; Levy, 1959; Patsiaouras & Fitchett, 2012). In many cases, products are perceived as symbolic tools. These symbols can serve in: (1) exposing, con-structing, maintaining, and enhancing an individual’s identity (Elliott & Wattanasuwan, 1998), (2) can signal group conformity or non-conformism (Elliott & Wattanasuwan, 1998) or (3) might signal social distinction (Levy, 1959). When it comes to signaling status and prestige, the Theory of Conspicuous Consumption gains importance (e.g. Gierl & Huettl, 2010; Levy, 1959; Nelissen & Meijers, 2011; Patsiaouras & Fitchett, 2012; Truong, 2010).

Conspicuous Consumption is defined as an act of attaining and exhibiting costly items to im-press others (O’Cass & McEwen, 2004; Trigg, 2001). This phenomenon of preferring more expensive over cheaper, yet functionally equivalent products was introduced over 100 years ago by Thorstein Veblen. Since then, psychological research has confirmed that the desire for status and prestige is an especially important force in driving the market for luxurious goods (Drèze & Nunes, 2009; Griskevicius et al., 2007; Rucker & Galinsky, 2008).

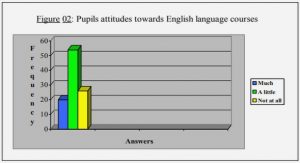

An aspect making the concept of Conspicuous Consumption essential for the luxury market – a market driven by the symbolic meanings of a good – is the assumption that the phenome-non of Conspicuous Consumption is a form of Costly Signaling (Dittmar & Drury, 2000; Nelissen Meijers, 2011; Sundie et al., 2011; Wang & Griskevicius, 2014). Conspicuous Consumption is a signaling process always involving the communication between two parties, namely the signaler and the recipient of the signal (Sivanathan & Pettit, 2010). This communication is seen as signaling game (Grafen, 1990; Zahavi, 1975). Within this game “certain traits and behaviors of organisms have a signaling function as they convey important information about the organisms to relevant others” (van Vugt & Hardy, 2009, p. 2). The relationship between the signaler, the signal and the recipient is depicted in Figure 2.

As aforementioned, by a display of costly and wasteful items the signaler strives to com-municate uniqueness, status or conformity with an exclusive social group (Chaudhuri Majumdar, 2006; Gierl & Huettl, 2010; Marcoux et al., 1997; O’Cass & Frost, 2002;Trigg, 2001). Hence, “why” the signaler engages in this signaling game has been shown by numerous authors (Belk, 1985; Berger & Shiv, 2011; Bliege-Bird & Smith, 2005; Chaudhuri Majumdar, 2006; O’Cass & McEwen, 2004; Tian et al., 2001; Vigneron & Johnson, 2004). The essential question is whether or not the signaler succeeds in the signaling game. A signaler succeeds, if the depicted signal is perceived as reliable.

Some authors argue that the costlier a particular signal is, the more reliable it will be (Maynard & Harper, 2003 cited in Fraser, 2012; Plourde, 2008; van Vugt & Hardy, 2009). Others believe that not only the costliness plays a crucial role (Han et al., 2010; Nelissen Meijers, 2011). While there is no clear definition on what comprises a reliable signal, it is however agreed that the ultimate outcome of the signaling game are the perceived « fitness benefits ». Nevertheless, it still requires further knowledge on “what” a product should look like in order to serve as a reliable signal and hence yield “fitness benefits”. This thesis will focus on this aspect.

To understand “what” a signal should look like, the following sections will firstly provide an overview about the “fitness benefits” that can be induced by displaying a reliable signal (see section 2.2). Secondly, the criteria for a reliable signal are discussed (see section 2.3 and 2.4). Finally, the importance of signals in a marketing connection and Generation Y will be addressed (section 2.5 and 2.6)

Fitness Benefits

The very nature of Conspicuous Consumption appears to be related to the benefits an individu-al obtains by displaying its possessions (Dittmar, 2004; O’Cass & McEwen, 2004). As al-ready recognized by Dittmar (1992), individuals define themselves as well as others in terms of their possessions; hence an individual’s identity is influenced by the symbolic meaning of his/her own material possessions. These possessions can serve as symbols for a person’s quality, attachments and interests (O’Cass & McEwen, 2004).

Nelissen & Meijers (2011) believe that people, who are seen as having a high degree of qualities/prestige, are rewarded with benefits in social interactions. The benefits an individ-ual receives comprise on the one hand an association with socially desirable traits. On the other hand individuals receive preferential treatment in social interactions (Bagwell & Bernheim, 1996; Nelissen & Meijers, 2011; O’Cass & McEwen, 2004; Sundie et al., 2011).

As the number of studies on “fitness benefits” is rather limited (Hambauer, 2012; Nelissen Meijers, 2011), the following section seeks to provide an overview of studies already car-ried out.

Status and Wealth

Status and wealth are, even though inherently different constructs, related when it comes to the Theory of Conspicuous Consumption (Godoy et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2015; Nelissen Meijers, 2011). The connection between status and wealth was initially addressed by Veblen who postulated that possessing financial resources is rewarded with status (e.g. Chaudhuri & Majumdar, 2006; Han et al., 2010; Mandel et al., 2006; Nelissen & Meijers, 2011; Patsiaouras & Fitchett, 2012; Saad & Vongas, 2009; Truong et al., 2008). The focal aspect within the Theory of Conspicuous Consumption is that status is only ascribed, if the dis-played financial possessions are wasteful and costly. This means that only those individuals are rewarded with status, that have costs in terms of energy, risk, time and money when producing a signal (Scott, 2010; Trigg, 2001). Since not everyone can afford these costs, they guarantee the reliability of the signal (Buchli, 2004; Fraser, 2012; Plourde, 2008; van Vugt & Hardy, 2009).

Several academics believe that especially the display of luxury accords for an attribution of status and wealth (Birtwistle & Moore, 2005; Han et al., 2010; Kastanakis & Balabanis, 2014; O’Cass & McEwen, 2004). This is accounted for by two aspects: On the one hand, Nelissen & Meijers (2011) believe that wealth is indicated, since it is a predisposition for buying luxury products in the first place. On the other hand, luxury goods can indicate a certain degree of “wastefulness”, since they cost more without providing any additional utility over their cheaper counterparts (Bagwell & Bernheim, 1996; Dubois & Duquesne, 1993; O’Cass & Frost, 2002). As mentioned earlier, Veblen (1899) claims that only those who can afford wasteful spending are perceived as having a high status (Trigg, 2001), thus they might reveal honest information about the qualities of a signaler. This information can be used to advertise “fitness” in the form of wealth and status (Lee et al., 2015; Nelissen & Meijers, 2011).

Although numerous authors still refer to The Theory of the Leisure Class, the market landscape has quite changed since Veblen (Chaudhuri & Majumdar, 2006). Luxury goods are still be-lieved to indicate status and wealth, however not purely because of the costs involved (Witt, 2010). Instead, the image and symbolic meaning of a product is consumed today (Chaudhuri & Majumdar, 2006).

Nowadays aspects such as conspicuousness, a signaler’s social group and the characteristics of the recipients are believed to have an impact on the perception of wealth and status (Hambauer, 2012; Han et al., 2010). Han et al. (2010) believe that a recipient’s own wealth and own longing for status play an essential role within the signaling game. Furthermore, the conspicuousness of a product has an impact on the perception of status and wealth, an aspect which was already addressed by Hambauer (2012). Though, what Hambauer (2012) did not take into consideration are the social context and the importance of a recipient’s characteristics. This shortcoming will be addressed in the research at hand.

Attractiveness

According to Cole et al. (1992, 1995), a conspicuous display of wealth can have a positive impact on the perceived attractiveness of a signaler. Likewise, Cole et al. (1992, 1995), De Fraja (2009), Hambauer (2012) Sundie et al. (2011) and Wang & Griskevicius (2014) claim that individuals, who conspicuously display evidence of their financial resources, are per-ceived as more attractive to the opposite sex. Males are especially believed to enhance their (short-term) mating desirability, when they conspicuously flaunt by displaying luxurious goods (Fraja, 2009; Sundie et al., 2011; Wang & Griskevicius, 2014). Independent of a man’s relationship status, by flaunting wealth on himself or his date, he was regarded as more desirable and attractive (Wang & Griskevicius, 2014). The effect of wasteful spending is not exclusively limited to luxury apparel, as men can signal attractiveness through any kind of wasteful spending (Gangestad & Simpson, 2000; van Vugt, 2008; Wang & Griskevicius, 2014; Waynforth & Dunbar, 1995).

Although the above mentioned studies primarily focused on males, Lee et al. (2015); Nelis-sen & Meijers (2011) as well as Van Vugt (2008) believe that signaling through wasteful ex-penditures does not only imply benefits for men. Hence, it cannot be assumed that solely men flaunting wealth are seen as more attractive.

Trustworthiness

According to Berger et al. (1980), those individuals, who are perceived as having a high sta-tus are more trusted, in that they are given more control over group decisions and enjoy more opportunities to contribute (Berger et al., 1980; Lount & Pettit, 2012; Podolny, 1993; van Vugt & Hardy, 2009).

Status and hence trust can be conferred by dispositions and reputation (Righetti & Finkenauer, 2011; Tinsley et al., 2002), as well as a person’s physical appearance (Krumhu-ber et al., 2007), which does not exclusively comprise physical attractiveness. Nelissen & Meijers (2011) as well as Hambauer (2012) believe that an aspect linked to a person’s ap-pearance is the display of a luxury brand. By displaying a luxury brand, an individual signals non-observable qualities such as trust (Nelissen & Meijers, 2011). Consequently Berger et al. (1980), Hambauer (2012) and Nelissen & Meijers (2011) state, that when a brand is dis-played in a conspicuous manner, a person is perceived as being more trustworthy

Competence

According to Schüpbach et al. (2005), competence is defined as a person’s abilities, knowledge and skills, that enable her/him to act effectively in business or private situations (Schüpbach et al., 2005). Based on the findings of Henrich & Gil-White (2001), Plourde (2008) and Rege (2008), it can be assumed that people signaling via wasteful and costly goods are perceived as more competent.

Rege (2008) believes that people tend to care about status and prestige as they serve as sig-nals of their non-observable abilities (Rege, 2008). If someone is perceived as having a high status, others are willed to cooperate with her/him as they believe that this person is par-ticularly competent, especially in a professional environment. This means that other indi-viduals with high business skills are more likely to cooperate with this person, since this person is believed to have likewise business skills. Though, as abilities are non-observable individuals must engage in signaling to communicate them. One way of signaling status and hence abilities, can be achieved by displaying luxurious goods. Displaying luxury goods therefore helps a businessman to increase his chances of making business contacts with (other) high ability people (Rege, 2008).

Plourde (2008) demonstrated in a game theoretical model that luxury goods are seen as honest signals of skills and knowledge. An individual strives to signal skills and knowledge as this leads to preferential treatments in social interactions. The source of this preferential treatment lies in the fact that a person, who is seen having a high knowledge, expertise, or advanced skill in some domain of activity, is perceived as prestigious (Henrich & Gil-White, 2001). Prestige consists of the authority and privilege given to an individual by oth-ers. Privileges and authority are experienced, as less skilled individuals admire, desire to know and are willed to defer to a prestigious person. Less skilled individuals seek to copy the highly skilled ones and wish being tutored by this person. In order to be tutored, lower skilled individuals try to please a prestigious person. This person hence receives a preferen-tial treatment (Plourde, 2008). Therefore, highly skilled individuals have a higher status and receive deference and privileges (Henrich & Gil-White, 2001).

Based on this, the postulate is made that luxury brands can serve as reliable signals for a person’s competences

Favorable Treatment

As discussed above, De Fraja (2009), Lee et al. (2015), Nelissen & Meijers (2011), Plourde (2008), Rege (2008) and Sundie et al. (2011) assume that a person is perceived as being “fit-ter” when signaling through costly and wasteful goods. The authors state that by displaying for instance a luxurious good a person is perceived as having a higher status and wealth, be-ing more attractive, trustworthy and competent. Due to these qualities, a signaling individ-ual is treated preferentially in social interactions.

Lee et al. (2015) as well as Nelissen & Meijers (2011) believe that people treat a person, who displays luxury brands, more favorable than the same person wearing an identical piece of clothing without a brand label. The authors claim that people are more compliant and generous to a person displaying a luxury good. Moreover, the authors believe that by wearing a luxury labeled apparel, a person is even perceived as more suitable for a job va-cancy. The recipients of a costly signal are on the one hand more willed to co-operate with a person signaling through a costly brand. On the other hand, a person flaunting a brand labeled shirt was even able to collect more money when soliciting for charity (Nelissen Meijers, 2011). Several researchers state that Conspicuous Consumption increases a signaler’s social capital resulting in a formation of alliances (Rege, 2008) that may even yield protec-tion, care, cooperation (Nelissen & Meijers, 2011; Plourde, 2008) and mating opportunities (Cole et al., 1992; Fraja, 2009; Sundie et al., 2011; Wang & Griskevicius, 2014).

To sum up – by displaying luxury brands an individual can (Hambauer, 2012):

- induce favorable treatment in social interactions,

- encourage an attribution of certain qualities,

- enhance his mating desirability,

- be confronted with a higher willingness for co-operation in both private and pro-fessional environments.

Luxury Brands as Symbols

Gierl & Huettl (2010) argue that not every product or brand qualifies as a symbolic tool, suitable for Costly Signaling. In order to qualify as a symbolic tool, a product must fulfill cer-tain criteria (Bliege-Bird & Smith, 2005; Gierl & Huettl, 2010; Nelissen & Meijers, 2011)

Fitness Benefits

Firstly, a brand can only then serve as a reliable signal if it yields a “fitness benefit” for the signaler (Bliege-Bird & Smith, 2005; Nelissen & Meijers, 2011; Zahavi, 1975). These “fit-ness benefits” are ultimately driven from the effects of Conspicuous Consumption (Bagwell & Bernheim, 1996; Nelissen & Meijers, 2011; O’Cass & McEwen, 2004).

Recent studies revealed that people assumed submissive postures when confronted with a person who displayed a luxury good (Fennis, 2008). Similar assumptions were also made by Nelissen & Meijers (2011). The authors showed within the scope of seven experiments that by displaying luxury goods, individuals can induce certain benefits in social interactions (Nelissen & Meijers, 2011)

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

1.2 Problem Discussion

1.3 Purpose

1.4 Delimitations

1.5 Key Terms

1.6 Structure

2 Theoretical Background

2.1 Conspicuous Consumption

2.2 Fitness Benefits

2.3 Luxury Brands as Symbols

2.4 Brand Prominence

2.5 Luxury Brands in a Marketing Perspective

2.6 Luxury Brands and Generation Y Consumers

2.7 Hypotheses

3 Methodology and Method

3.1 Research Philosophy – Realism

3.2 Research Approach – Deductive Approach

3.3 Research Purpose – Conclusive Study

3.4 Research Design – Quantitative Research

3.5 Data Collection Method

3.6 Experimental Design

3.7 Analysis Techniques

3.8 Screening and cleaning the data

3.9 redibility of research findings

4 Empirical Findings

4.1 Descriptive Statistics

4.2 Hypothesis Testing

5 Interpretation

5.1 Importance of a respondent’s characteristics

5.2 Perceived qualities

5.3 Favorable Treatment

5.4 A new kind of Conspicuous Consumption

5.5 Symbolic Meaning of Brands among Gen Y

5.6 Costly Signaling as cultural defined phenomenon

6 Conclusion

7 Discussion

7.1 Contribution

7.2 Limitations

7.3 Further Research

8 List of References

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT