Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Focus on integration and disintegration in Europe

The European Union: an illustration of a deep form of integration Deep integration

The EU has been a precursor of deep integration. Mulabdic et al. (2017) build a measure of “depth” based on the number of provisions covered by the agreement and show the EU is the deepest PTA among the 279 currently in force. The relationship between the EU members is regulated by the European Community Treaty and the following enlargement agreements, which cover 44 policy areas ranging from standards to movements of capital, to labor mobility. Europe is also the region that has the largest share of intra-regional trade. In addition, the EU provides an intense network of trade relations and a deep integration of each member in regional value chains. The EU Customs Union and Single Market are the marks of a deep integration (economic and political), compared to a shallow integration (purely economic).

EU integration effects

The EU integration impacts have been widely assessed, using different methods usually employed for the integration effects quantification, and focusing on different economic channels, e.g. FDI, trade and welfare. Bruno et al. (2017) estimate that the impact of EU membership on trade and FDI are substantial: e.g. the EU membership increases FDI inflows by on average 28%. Mayer et al. (2019) estimate the economic gains from European integration through the trade channel: all member countries unambiguously obtain sizable welfare gains from the EU as it is. They provide quantified evidence of the welfare brought by the EU to the population of member countries, which is also the “costs of non-Europe”, weighted by country size. These costs are estimated to vary between 2% and 8% depending on the counterfactual (RTA vs. return to WTO rules). Other dimensions of European integration matter and can be assessed, such as the free mobility of capital and labor or the effects of the euro. Campos et al. (2015) estimate the benefits from economic integration generated by political factors and by the complementarity between economics and politics, disantangling the economic from political determinants. They take the example of Norway, which ended up being fully economically integrated with the EU but not politically integrated. In addition, policies supporting integration, such as low taxes, flexible labor legislation, deregulation, privatization, and openness are pursued by governments in order to earn market confidence and attract trade and capital inflows (Rodrik, 2000).

Integration also provides non-economic gains (or losses), political stability being probably the most important of those. Martin et al. (2012), and Vicard (2012) emphasize the security gains associated with regional trade integration (Mayer et al., 2019). Concerning migration, Simionescu (2018) assesses the impact of European economic integration on migration in the EU15, from the newly integrated EU countries (cf. the recent enlargement of the EU, since 2004). In the 2000-2015 period, the number of migrants from the new member states of the EU has increased, in average, with more than 2200 people only due to their EU mem-bership. This result reflects the positive impact of European economic integration on the number of emigrants from the Central and Eastern Europe countries that chose the EU15 states as destination countries. Finally, according to Lavery et al. (2019), Brexit created an opportunity for alternative European financial centres, and the corresponding economic benefits, in the aftermath of Brexit. Significant business functions are likely to leave the City of London and relocate to inside the Eurozone, Frankfurt and Paris being two of the main “rivals” to the City of London.

From a deep integration to Brexit

Economic gains brought by the EU to all members are indisputable. The UK economy is part of the intense network of trade relations forged over the years by the EU, which has brought several advantages. At present, the EU is the most important trade partner of the UK, accounting for 52% of the UK’s exports of goods and services. In addition, the UK is closely integrated in regional value chains. For instance, the share of intermediate value added on total domestic value added in UK exports (the majority of which goes to the EU) is close to 70% (Mulabdic et al., 2017).

From a more historical point of view, some studies are interested in the gains from the EU accession, with respect to the UK’s situation before joining the EC (and later the EU). For instance, Gasiorek et al. (2002) provide a decomposition of the welfare impact on the UK arising from the changes in manufacturing trade consequent upon joining the EC, with a CGEM of manufacturing trade incorporating imperfect competition and firms’ specific increasing returns to scale to study the accession of the UK to the EC in the early 1970’s. The results suggest that gains from European integration come less from the traditional theory of integration (trade creation and trade diversion) and more from imperfectly competitive approaches to trade theory which emphasize economies of scale, and the impact on the competitive environment. While the welfare impact could indeed be relatively small, this depends on the extent to which the process of integration leads to changes in competitive interaction. The greater the pro-competitive impact of integration, the higher are the potential welfare gains.

To balance this consideration, we remind that the UK was not part of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), and Rose and Engel (2000) find that members of currency unions are more integrated than countries with their own currency. Currency union members have more trade and less volatile exchange rates than countries with their own currency. As a result, it seems that the UK did not benefit from these positive effects, contrary to the fully integrated EU members.

But in spite of the global benefits brought by the EU to all members, including the UK, it finally ended with the Britain exit. Even if the existence of the EU27 is not called into question nowadays, Brexit represents a case of disintegration in the sense that the economic agreement between the EU and the UK is coming undone. While one of the big questions related to Brexit concerns a potential trade agreement between the EU and the UK, or an absence of it, Brexit is more than about trade.

Brexit literature as a disintegration case

Over the last four years, a number of studies evaluating the economic costs and benefits of Brexit have emerged in the literature using different types of methodological approaches. I proposed in Section 3.1 of the present paper a Brexit review focusing on Brexit as a shock, changing trade policies and increasing trade costs, on agri-food sector. To sum up, we highlight that a large number of works evaluate the effects of Brexit using a computable general equilibrium model (e.g. Bellora et al., 2017; OECD, 2016; Jafari and Britz, 2018; Figus et al., 2018) or structural gravity models (e.g. Dhingra et al., 2017; Oberhofer and Pfaffermayr, 2018).

In this section we are more interested in the positioning of the method of disintegration impacts assessment in comparison to integration, considering Brexit as a specific illustra-tion of disintegration. From this perspective, we notice that some recent papers are located at the crossroads of two strands of economic literature: the literature that investigates the impact of trade agreements on members’ trade relations, and the recent literature that focuses on the economic and trade effects of Brexit, such as Mayer et al. (2019); Mulabdic et al. (2017); Campos et al. (2014); Crafts (2016); Bruno et al. (2017); Mayer et al. (2019). Mayer et al. (2019) revisit the gains the EU has reaped from trade integration since 1957 and what would be the costs of going backwards (i.e. the cost of non-Europe). Mulabdic et al. (2017) wonder what would be the impact of undoing trade agreements on trade. They address this question by focusing on the effect the EU membership had on the UK trade, most notably with its European partners, and then use this information to assess the future of UK-EU trade under different scenarios. They find that EU membership had a strong impact on UK-EU trade and that it contributed particularly to the rise of UK services exports and its integration in global value chains. They then analyse the impact that changes in the UK-EU trade agreement can have on UK-EU trade relations going forwards. They consider distinct scenarios, with decreasing depth of the future agreement between the UK and the rest of the EU. They find that there is a clear trade-off between the depth of such agreement and the intensity of future UK-EU trade. In particular, a shallower agreement will have a stronger negative impact on the UK’s services trade and global value chain integration, which have relied more on the deep arrangements of the EU.

In this new strand, the main methods used consist in quantifying the effects of EU inte-gration in order to evaluate what would be the cost of non Europe, or of a step backwards in integration. The idea is to assimilate the effect of Brexit to the opposite of the EU membership effect, and use counterfactual analysis to evaluate its impacts of economic growth, GDP, FDI, and trade. Basically, the same methods are used for both integration and disintegration, playing with the increase or decrease of trade costs or the depth of integration. We find this trend even in a linguistic approach: the word “disintegration” is rarely used. In the appendices I present an Econlit 29 occurence research of the words “integration” and “disintegration” showing the relatively low occurrence of the latter, compared to the first, over the years. This analysis is in line with Sampson (2017) which reviews the literature of the potential economic consequences of Brexit. According to him, researchers have used three approaches to estimate the effects of Brexit: (1) historical case studies of the economic consequences of joining the EU; (2) simulations of Brexit using computational general equilibrium trade models, and (3) reduced-form evidence based on estimates of how EU membership affects trade.

Yet, a disintegration is not totally equivalent to an integration unraveling. Let’s take the example of NTMs. It is highly unlikely that the UK will return to the same level of NTMs than before joining the EU. Now they are harmonized, a high divergence would cost too much. The way Dhingra et al. (2017) address NTMs issues is a good illustration. They use information provided by Berden et al. (2009): the NTMs level between the EU and the USA, but also the fraction of these NTMs that is reducible for each sector, i.e. the fraction of the trade cost that could in principle be eliminated by policy action. 30 As it is unlikely that the UK will face the same NTMs as the USA following Brexit, in the soft Brexit scenario they assume the UK faces one-quarter (1/4) of the reducible NTMs faced by the USA, while in the hard Brexit scenario they assume UK-EU trade is subject to three-quarters (3/4) of the reducible NTMs. Brexit is not seen as the exact reverse of the EU.

Even since the Brexit vote, interest in disintegration, or integration unraveling (i.e. reverse of integration) has been more limited than in integration itself. Campos et al. (2014) even say that one of the few undisputed benefits from Brexit is that it motivated a huge amount of new research on the political economy of deep integration. Yet, we live in an age where it seems that the most likely outcome in the near future might be one of trade disintegration in Europe, possibly reversing one of the deepest and most prolonged trade liberalization process in modern history. The choice of the UK to exit the EU, combined with the calls from many governments for a reversal of key integration agreements like Schengen, can lead to more disintegration in the future (Mayer et al., 2019). These observations suggest that disintegration will be the subject of some studies and interests in the near future. One of the positive spillover effects could be the developement of new research on disintegration effects, regardless of integration, and using new methods.

In the following, we aim to highlight the mechanisms: why did Brexit happen? Why could it be the sign of a new disintegration wave? In other words, what does Brexit mean for the future of the EU and, more broadly, global economic integration?

A new wave of disintegration?

In this section we analyse and highlight some potential causes of the most recent disinte-gration, namely the Brexit. In addition, we wonder and analyse whether we are entering in a new disintegration era (new political sequence), whose Brexit marks the beginning.

Brexit causes

Globalization and disintegration are topics at the crossroads of several fields. Many ques-tions have been raised, in different research areas, such as economics, politics, sociology. In particular, economic integration appears to be closely linked to politics, and can have impacts on other fields such as democracy or sovereignty. For instance, a branch of litera-ture focus on public opinion and support (or non support) for EU integration. According to Hobolt and De Vries (2016), older studies such as Gabel and Palmer (1995); Inglehart (1970); Sánchez-Cuenca (2000) focus on support for European integration whereas the focus in the last decade has shifted to opposition to European integration, or so-called Euroskepticism, e.g., Hakhverdian et al. (2013); Hooghe (2007); Leconte (2010).

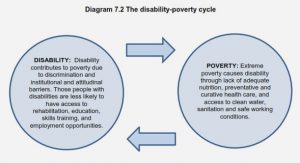

In the case of EU and UK, a deep (political) integration has led to a disintegration, namely the Brexit. According to Sampson (2017), support for Brexit came from less educated, older, less economically successful and more socially conservative voters who oppose immigration and feel left-behind by modern life. With the referendum the debate was about whether the UK should prioritize remaining economically integrated with the EU or taking control of immigration and economic regulation. Integration lost. Why? Is it possible to extract the elements that led to this end? We try here to better understand the causes, or hypotheses of causes. More broadly, Brexit raises questions about the future stability of the EU and the future of the globalization.

Table of contents :

1 International trade and economic integration in theory and practice

1.1 History of economic thought and trade theory: why do we trade?

1.2 Gravity, a workhorse for analyzing bilateral trade flows

2 Brexit, a globalization halt?

2.1 Free trade and trade integration evolution

2.2 A disintegration episode called Brexit

3 Importance and vulnerability of agri-food production and trade in the European Union

3.1 Agricultural and food sectors in the EU member states

3.2 Agricultural and food sectors in France and Brittany

3.3 Agricultural and food sectors in Ireland

4 Problem statement, objective and research questions

I Brexit context and economic disintegration

1 Introduction

2 Brexit context: EU membership history of UK, vote and negotiations

2.1 EU-UK history and relationship until 2016

2.2 2016-2020: negotiations and stakes, from referendum to actual Brexit

3 Brexit effects on UK and EU agri-food sector

3.1 Brief literature review

3.2 Some stylized facts about EU, France and the context of Brexit

4 Economic integration: definitions, historical approach and evolution

4.1 Definitions: globalization, levels of integration, trade agreements

4.2 Economic integration impacts assessment

4.3 Global economic integration evolution in the pre-Brexit history, and some cases of disintegration

5 From European deep integration to Brexit disintegration, and beyond?

5.1 Focus on integration and disintegration in Europe

5.2 A new wave of disintegration?

6 Discussion and conclusion

Appendix A – HS nomenclature

II Brexit and European agricultural and food exports

1 Introduction

2 Context of negotiations and scenarios: a brief review of the literature

2.1 Ongoing negotiations

2.2 Quantifying Brexit trade effects, a brief literature review

2.3 What about the possible scenarios?

3 Methodology and data

3.1 Structural gravity

3.2 Estimation strategy

3.3 Data

4 Results at the aggregate level

5 Effects by groups of products

6 Conclusion and further work

Appendices

III Brexit et exportations alimentaires Bretonnes

1 Introduction

2 La Bretagne agricole et agro-alimentaire: produits phares et partenaires commerciaux privilégiés

2.1 Production alimentaire bretonne

2.2 Commerce extérieur breton: viande et produits laitiers

2.3 Le Royaume-Uni, un partenaire commercial majeur de la Bretagne

dans l’alimentaire: viande, fruits et légumes, céréales, produits de la mer

2.4 La Bretagne face au Brexit

3 Méthodologie et scénarios

3.1 Modèle de gravité structurelle

3.2 Stratégie d’estimation et scénarios

4 Données internationales, françaises et bretonnes

4.1 Données observées

4.2 Prédiction des données manquantes

4.3 Résultats et robustesse des données reconstituées

4.4 Correction des données reconstituées avec l’effet frontière

5 La vulnérabilité de la Bretagne face au Brexit

5.1 Estimation du modèle de gravité

5.2 Simulation des scénarios

6 Discussion et conclusion