Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

WATER, SANITATION AND HYGIENE IN HAITI

To “ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all” is UN’s Sustainable Development Goal no.6. Access to water and sanitation are indeed a Human Right since 20107. Still, 29% of the global population lack access to safe drinking water and 61% are without safely managed sanitation services8.

But there is a third element to add to water and sanitation: hygiene. All three words make up what is known in development as WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene). The effects of a lack of all three elements can be perfectly identified in a cholera outbreak as was the case in Haiti. According to a WHO report, cholera and other diarrhea related diseases are linked to different transmission pathways which have to do with water, hygiene or sanitation, or a combination of them: ingestion of unclean water, lack of water linked to inadequate personal hygiene, poor personal, domestic or agricultural hygiene, contaminated water systems, etc. (WHO, 2014). But as well as a combination of water, hygiene and sanitation deficit is able to trigger diarrheal diseases as cholera, it has been proven that an integral intervention may reduce the risks in developing countries up to a 12% reduction rate. This means that up to 1.000 lives may have been saved from the Haitian Cholera outbreak with proper WASH facilities and knowledge.

WASH conditions in Haiti were already a growing problematic even before the 2010 earthquake. Before the disaster, only 69% of Haiti’s population had access to safe water and 17% to improved sanitation facilities9. Sanitation coverage decreased from 26% in 1990 to 17% in 2008 (Tappero & Tauxe, 2011). Disparities between urban and rural areas were evident: 85% against 51% of access to safe water, and 24% against 10% of access to improved sanitation, respectively10. A reform of the water and sanitation sector was voted in the Haitian parliament in March 2009, only 10 months before the earthquake. This propitiated the creation of the National Directorate for Portable Water and Sanitation (DINEPA by its French acronym). But DINEPA’s focus shifted from long term development to emergency response right after the earthquake. At the same time, foreign governments, multi-lateral lending institutions, NGO’s and other organizations were also committed to improve WASH conditions then. More than 100 NGO’s were identified to develop projects intended to improve WASH conditions in addition to a multitude of small-scale projects from small faith-based groups (Gelting et al., 2013).

The efforts had some good results and “residents of IDP camps had been largely spared from the outbreak because of safe water supplies and improved sanitation” (Tappero & Tauxe, 2011, p.2091). Some of the developments included increased chlorination of water supplies, rehabilitation of distribution networks and water treatment stations, distributions of household water treatment products and soap, and cholera prevention and hygiene promotion campaigns (Gelting et al., 2013). However, these efforts were mostly emergency response. In the following years, many activities ceased, while DINEPA retook some of the reforms planned in 2009. A ‘National Plan of Action for the Elimination of Cholera in Haiti’ was approved by the Ministry of Public Health and Population (MSPP by its French acronym) which provided 2.2 billion U.S. dollars for the eradication of cholera, of which 70% were designated to developments in the WASH sector11 through DINEPA. Nowadays, Haiti’s score of the SDG no.6 went from 54% in 2017 to 61% in 201812, confirming the good progress of WASH improvements in the country.

HEALTH COMMUNICATION AFTER THE CHOLERA OUTBREAK

One of the 9 specific objectives set by MSPP for the eradication of cholera was “that by 2022, 75% of the general population in Haiti will have knowledge of prevention measures for cholera and other diarrheal illnesses”13. Right after the cholera outbreak, NGO’s and public institutions immediately lead health communication campaigns tackling the risk of cholera infection and encouraging the population to pay attention to WASH recommendations. These campaigns were targeted both to health professionals and general population with the aid of the Center for Disease Control (CDC) (Tappero & Tauxe, 2011). Moreover, MSPP broadcasted messages, displayed banners, and sent text messages encouraging people to take specific measures to prevent cholera. Even Haitian President René Préval led a 4-hour televised public conference to promote cholera prevention.

In May 2011, an investigation and joint statement by US researchers informed that in the first two months after the outbreak, IDP camp managements implemented 670 cholera risk-reduction activities in camps and their surrounding communities. “UN education cluster partners distributed cholera prevention and water treatment protocols in schools across the country; phone companies, along with the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, the International Organization for Migration, and others, sent public health warnings via SMS; and radio stations dedicated broadcasts to education programs, provided updates from the MSPP, and answered caller questions” (Farmer et al., 2011).

RESEARCH DESIGN

The present thesis covers the impact of Health/WASH communication campaigns in Haiti with a particular focus on one specific communication tool: video. Its specific goal is to compare health communication video initiatives working towards cholera prevention and the promotion of water, sanitation and hygiene practices in Haiti.

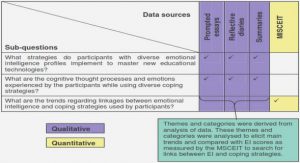

The methodology for the study is based on comparative research using two different methods: first, the comparison of video initiatives and their content by way of content analysis; secondly, by analyzing the coherence -or not- of such content with the video’s target audience perception by a survey analysis exercise. It is a sequential process, which means that the survey analysis depends on the content analysis findings to determine the content used for the questionnaires. In other words, the survey analysis uses questionnaires which questions are derived from the issues highlighted by the content analysis. This is an important feature of the research as it increases the reliability and validity for the survey exercise in a significative way.

RESEARCH QUESTION

From the description above, the research question can be easily stablished: What are the similarities and differences between different health communication videos tackling WASH/cholera regarding content portrayed and content perceived by the target audience?

First, the question reveals that it is a double-sided research question: on one side, the content shown or portrayed by the videos regardless of the public to which it is directed; on the other side, the content understood or perceived by the identified target audience to which the videos are directed. It does not mean there are two questions or even more in the research question, though. The “content portrayed” and “content perceived” part of the question might be summarized as “impact”, but then, the two phases of the transmission of content would not be as evident in the questions. The same is applied to “similarities and differences”, which are the two objectives from comparative research. In fact, a first draft only included “differences”, but “similarities” was included afterwards.

What is the purpose of asking this research question? What do I pretend to achieve with it which may be relevant to Communication for Development? Why should the answer to this question matter? The approach to Communication for Development in this thesis, as it will be explained in more detail in the concluding chapter, is linked to the notion of “seeking change”14 and more specifically to the field of Social and Behavior Change Communication (SBCC). By comparing the “impact” (content portrayed vs. content perceived) of these video initiatives we will be able to identify which of them has had more success and effectiveness, or which health messages were retained by the target audience, which have not been retained. Therefore, the question is leading us to understand what is the impact (change) in the target audience’s mindset, and also what changes need to be made in order to be more effective in transmitting content: Are the videos effective in order to transmit at least the basic ideas of cholera prevention practices? To what extent (percentage)? Is one video more successful than the other in the general perspective? What issues are highlighted in these videos both in terms of the message and the retention of it by the target audience? Were the messages in the videos captured by the viewers’ mind? All these are subsequent questions that derive naturally from the primary research question.

Almost every health communication program in developing countries seeks some kind of change (Bertrand, Babalola & Skinner, 2012). This case is not an exception. Our study, however, does not deepen into the visible behavior change processes, but rather focus on the cognitive side of behavior change among children, that is the initial phase of behavior change. It humbly tries to set the ground for further SBCC interventions and communication campaigns which might profit from the findings.

UNITS OF STUDY

Ti-Joel “Campaign Against Cholera” by UNESCO Haiti and MSPP

The UNESCO Campaign Against Cholera implemented after the 2010 cholera outbreak consisted of several resources integrating a famous Haitian cartoon character, Ti-Joel, “to show young people how to protect themselves from cholera at school and outdoors, how to purify water and how to prepare oral serum”15. A total of six short animated films were produced and spread through national public TV as well as private TV channels and made available in internet and social media16. Apart from these, a 44-page comic book was also created with the same stories. It was distributed by the Haitian Ministry of National Education and Vocational Training, UNICEF, PAHO/WHO and other organizations in schools, recreations centers for children, IDP camps, libraries, community centers, scout organizations, health centers and cholera treatment centers17. For the sake of time and focus, only one of the six videos has been selected for study. The selection criteria was mainly based on similarities to other videos used in the study, length -the more length, the more content-, and number of shots and sequences -the more shots and sequences, the more content too-. The selected video can still be found in the UNESCO official Youtube channel18.

“The story of cholera” by Global Health Media Project

The Global Health Media Project (GHMP) is a non-profit organization that designs and produces video and animation video to teach healthcare practices for frontline health workers and families in low-resource settings (Monoto & Alwi, 2018). Both “The story of cholera” and “The story of ebola” videos are of important success for the purpose of developing short films to use during epidemic crisis to teach citizens on how to deal with the disease and how to prevent it. However, there are a high number of videos available at its website for different healthcare issues19.

“The story of cholera” was produced in response to the Haitian cholera epidemic outbreak in 2010 in order to help “affected populations around the world better understand cholera and how to prevent it”20. It was dubbed into 35 different languages and it “has become a favorite educational tool among communication for development specialists, aid workers, animators, and public health experts”21. According to the GHMP website, “several experts made sure that the technical information on cholera was accurate and up-to-date”, among them UNICEF’s Deputy Coordinator of the WASH cluster in Haiti in 2011. The video may be watched and downloaded at the GHMP platform22.

“Cholera Prevention” by Scientific Animations Without Borders

Scientific Animations Without Borders (SAWBO) is an initiative from the University of Illinois seeking to provide animation materials on different development topics in local languages in order “to improve the livelihoods of low-literate learners” (Bello-Bravo, Olana & Pittendrigh, 2015, p.27). Topics covered by the SAWBO videos include: agriculture, health, women empowerment and economic development. Most of the videos are short 3-D animation. These are produced through partnerships and collaborations, and made available through the website, but also via the University of Illinois online library system as well as provided by SAWBO for communication for development projects through a recent Deployer app developed for field workers23.

The cholera prevention video was also created for the specific context of the Haitian outbreak in 2010, months before the SAWBO project was officially launched (Miresmailli, Bello-Bravo & Pittendrigh, 2015). “A script was given to the animation team, and the animation was then created and reviewed. Upon approval, language overlays were created in Creole, French, Spanish, and English, and the animations were given out to a diversity of organizations for free distribution” (Bello-Bravo, Seufferheld, Steel, Agunbiade, Guilot & Pittendrigh, 2011, p.55). The cholera prevention video is available for watching and downloading at the SAWBO platform24.

Table of contents :

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 HAITI AND CHOLERA

1.2 WATER, SANITATION AND HYGIENE IN HAITI

1.3 HEALTH COMMUNICATION AFTER THE CHOLERA OUTBREAK

1.4 RESEARCH DESIGN

1.4.1 RESEARCH QUESTION

1.4.2 UNITS OF STUDY

1.4.3 COLLABORATION WITH GAIN AND COGOP ORPHANAGE & SCHOOL

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

2.2 HEALTH COMMUNICATION IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

2.3 CONTEXTUALIZED VIDEO IN HEALTH COMMUNICATION CAMPAIGNS FOR DEVELOPMENT

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1 COMPARATIVE RESEARCH

3.2 CONTENT ANALYSIS OF CHOLERA PREVENTION VIDEOS

3.3 SURVEY ANALYSIS THROUGH QUESTIONNAIRES

3.4 DISCUSSION ON THE METHODOLOGY

4. FINDINGS

4.1 CONTENT PORTRAYED

4.2 CONTENT PERCEIVED

5. LIMITATIONS

6. CONCLUSION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

APPENDICES