Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Assumptions and misconceptions

Good intentions regarding empowerment initiatives may be hampered by misconceptions, which may also have the potential to limit the benefits of empowerment objectives. A potential danger is that economic benefits for individuals and groups of people enjoy more prominence than the improvement of competence, confidence and performance in general. An assumption that is generally made is that the goal of empowerment is to correct the injustices of the past. Empowerment as an organisational development strategy can easily be confused with the political or socio-economic meaning of empowerment as BEE presently governs empowerment policies and dominates the business scene in South Africa. The main goal seems to be that more black people participate in the decision-making processes of organisations, while the value and potential of empowerment as a means of enhancing human potential and to develop competence should be equally important.

The influence of contextual factors

Adler (1928) recognised the influence of the socio-economic environment on people’s thinking and behaviour. He contended that an evaluation of individuals could only be made when their context, their environment, is known and warned that erroneous conclusions would be the result if single phenomena are judged. More to the point of empowerment, Conger and Kanungo (1988) identified contextual factors that contribute to the lowering of self-efficacy beliefs in organisational members. Therefore, a perspective of the South African state of psychological empowerment should be investigated by taking in consideration contextual factors. Suggesting that socio-economic factors have implications for the interpretation of the concept, empowerment, may be difficult to investigate. Suggesting that an organisation’s empowerment strategies, whether compelled by politics or not, have an effect on experiences of empowerment is more feasible for measurement, although to take the environmental influences into account more completely, both the individual level and the organisational level need to be considered. But whatever the focus, be it economic or psychological, management should be informed and understand the social processes that affect employees’ work related attitudes, and contribute by providing a climate that is conducive to empowerment (Mok & Au-Yeung, 2002).

THE CONCEPT: PSYCHOLOGICAL EMPOWERMENT

Empowerment has become one of the most prominent concepts in modern management theory and practice, as well as organisational psychology studies (Whetton & Cameron, 1995). Empowerment per se is a concept widely used within organisational science (Blanchard, Carlos & Randolph, 1999; Conger & Kanungo, 1988), while psychological empowerment has its origin in cognitive psychology. Bandura’s (1977) theories of psychological change in terms of cognitive processes are grounded in cognitive psychology and Thomas and Velthouse (1990) presented a cognitive model of empowerment. Spreitzer and Quinn (1997) based their findings on empowerment on empirical research in the fields of management and organisational behaviour. Zimmerman (1995) expanded his study from psychological empowerment on an individual level to include organisational or community empowerment, which suggests ties with organisational and community psychology.

Learned helplessness

Seligman (cited in Hock, 2005) used the term, learned helplessness, and proposed that perceptions of power and control are learned from experience. He based his studies on the belief that when a person’s efforts at controlling certain life events fail repeatedly, the person may stop attempting to exercise control altogether. If these failures happen often enough, the person may generalise the perception of lack of control to all situations, even when control may actually be possible. People then tend to give up, admit defeat, become helpless and feel depressed (Hock, 2005; Seligman & Maier, 1967). Brown (1979) referred to studies in learned helplessness in humans that demonstrated that a variety of experiences, the most typical being adverse consequences of failure at unsolvable tasks, can undermine subsequent performance. Expectations of controllability have an effect on the development of feelings of helplessness.

Locus of control

Rotter (1966) proposed that individuals differ in where they place the responsibility for what happens to them. When people interpret the consequences of their behaviour to be controlled by luck, fate or powerful others, this indicates a belief in what Rotter called an external locus of control. Conversely, he surmised that if people interpret their own behaviour and personality characteristics as responsible for behavioural consequences, they have a belief in an internal locus of control. In childhood development behaviours are learned because they are followed by some form of reinforcement. This reinforcement increases the child’s expectancy that a particular behaviour will produce a desired reinforcement. Once this expectancy is established, the removal of reinforcement will cause the expectancy of such a relationship between behaviour and reinforcement to fade.

Control and choice

Control and choice are described by some authors in terms of perceptions. Perception was defined by Giorgi (1983) as the process by which one becomes aware of one’s environment by interpreting the evidence of the senses. According to Steiner (1979), individuals experience a sense of control when they feel that they, rather than external factors, determine the outcome, while choice has to do with the perception of freedom of choice to decide which of two or more options will be accepted. Steiner speculated that there are three kinds of choice: people experience choice when they seem to control the decision-making process in that they may select an alternative they desire (evaluative choice); they confidently select among available options (discriminative choice); or by processing and evaluating information, they identify an alternative that seems best for them (autonomous choice). Harvey, Harris and Lightner (1979) also distinguished between the concepts of perceived freedom and perceived control. They too saw perceived freedom as an experience associated with the act of deciding between alternatives. Compared to perceived freedom to choose, perceived control was seen as the ability to gain control over the course that one has chosen.

TABLE OF CONTENTS :

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- LIST OF TABLES

- LIST OF APPENDICES

- SUMMARY

- 1 CHAPTER 1: PSYCHOLOGICAL EMPOWERMENT IN CONTEXT

- 1.1 INTRODUCTION

- 1.2 BACKGROUND

- 1.3 MOTIVATION FOR THE RESEARCH

- 1.3.1 Assumptions and misconception

- 1.3.2 The influence of contextual factors

- 1.3.3 Problem statement

- 1.4 THE CONCEPT: PSYCHOLOGICAL EMPOWERMENT

- 1.4.1 Definitions

- 1.4.2 Relevant paradigms

- 1.5 RESEARCH QUESTIONS

- 1.6 AIMS

- 1.7 DESIGN AND METHOD

- 1.8 OVERVIEW

- 2. CHAPTER 2: THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

- 2.1 INTRODUCTION

- 2.2 CONCEPTS

- 2.2.1 Powerlessness

- 2.2.2 Learned helplessness

- 2.2.3 Control

- 2.2.4 Locus of control

- 2.2.5 Control and choice

- 2.2.6 Power

- 2.2.7 Meaning

- 2.2.8 Competence-incompetence

- 2.2.9 Self-determination

- 2.2.10 Impact

- 2.2.11 Self-efficacy

- 2.2.12 Optimism

- 2.2.13 Empowerment defined

- 2.3 THEORIES AND MODELS

- 3. CHAPTER 3: LITERATURE SURVEY OF PREVIOUS RESEARCH

- 3.1 INTRODUCTION

- 3.2 DEMOGRAPHIC VARIABLES

- 3.2.1 Gender

- 3.2.2 Race and disadvantaged groups

- 3.2.3 Status / position

- 3.2.4 Level of education

- 3.2.5 Sectors

- 3.2.6 Age

- 3.2.7 Experience and tenure

- 3.2.8 Relevance of demographic variables

- 3.3 ANTECEDENTS OF EMPOWERMENT

- 3.4 INTERRELATIONSHIPS

- 3.4.1 Nomological network

- 3.4.2 A social cognitive theory framework

- 3.4.3 Relevance of interrelationships

- 3.5 IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH ON PSYCHOLOGICAL EMPOWEMRENT

- 3.5.1 Contextual analysis

- 3.5.2 Components of psychological empowerment

- 3.5.3 Suggestions

- 3.5.4 Other considerations

- 3.5.5 Qualitative research

- 3.6 CONCLUSION

- 3.7 SUMMARY

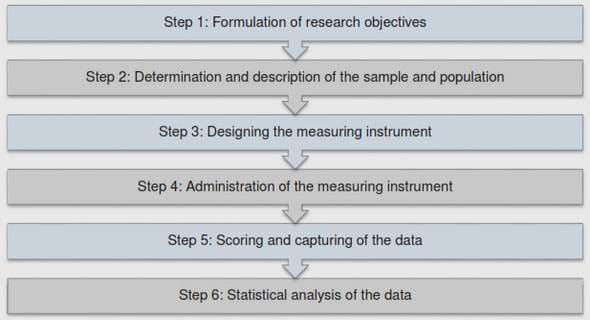

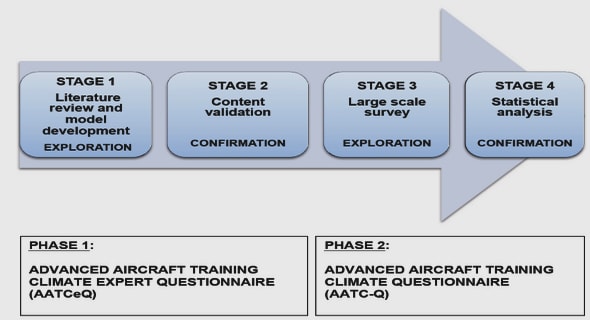

- 4. CHAPTER 4: RESEARCH METHOD

- 4.1 INTRODUCTION

- 4.2 PARADIGMS

- 4.2.1 Phenomenological approach

- 4.2.2 Convergent and divergent approaches

- 4.2.3 Inductive and deductive approaches

- 4.2.4 Scientific approach

- 4.2.5 Practical and applicable

- 4.3 RESEARCH DESIGN

- 4.4 SAMPLE STRATEGY

- 4.4.1 Identifying the population

- 4.4.2 Sample size

- 4.4.3 The sample population

- 4.4.4 Description of the sample

- 4.4.4.1 Quantitative phase

- 4.4.4.2 Qualitative phase

- 4.5 METHODS OF DATA COLLECTION

- 5.2.1.2 Discussion

- 5.2.2 Race differences

- 5.2.2.1 Results

- 5.2.2.2 Discussion

- 5.2.3 Position in the organisation

- 5.2.3.1 Results

- 5.2.3.2 Discussion

- 5.2.4 Educational level

- 5.2.4.1 Results

- 5.2.4.2 Discussion

- 5.2.5 Sectors

- 5.2.5.1 Results

- 5.2.5.2 Discussion

- 5.2.6 Methods of empowerment

- 5.2.7 Other observations

- 5.2.8 Conclusions

- 5.3 STATE OF PSYCHOLOGICAL EMPOWERMENT

- 6. CHAPTER 6: PERCEPTIONS OF EMPOWERMENT

- 7. CHAPTER 7: DIMENSIONS OF PSYCHOLOGICAL EMPOWERMENT

- 8. CHAPTER 8: ANTECEDENTS OF EMPOWERMENT

- 9. CHAPTER 9: INTEGRATION OF FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATION OF EMPOWERMENT STRATEGIES

- 10. CHAPTER 10: CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT

PSYCHOLOGICAL EMPOWERMENT: A SOUTH AFRICAN PERSPECTIVE