Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Chapter 3 Knowledge Management Strategies

Some people do not become thinkers simply because their memories are too good.

Anonymous

Introduction

In this chapter, some of the more important processes of KM which were found in the review of the current literature on the application of KM in industry will be presented. Since the designations are not uniform in the literature, the descriptions are to be understood not as generally accepted definitions, but as representation of typical views. There are considerable variations in the literature with regard to the applications of individual processes or activities, which may also be regarded as components of knowledge management. A working definition will suffice for now: ”Knowledge Management can be described as the collection of processes that govern the creation, dissemination and utilisation of knowledge to fulfil organisation objectives” [Bawany, 2000:38]. Figure 3.1 depicts the main KM processes 1:

This chapter begins with a review of the main KM strategies practised by most organisations by using Figure 3.1 as a template for the discussion of the KM processes of knowledge creation, dissemination and utilisation. These are discussed in section 3.2, where an outline of the defi-nition of knowledge is given, as it is understood within the context of this thesis, and what it means for this research in relation to the research question. The research problems are revis-ited, thus allowing a discussion of strategic significance of how these processes may be used to manage KM projects. This section ends with a summary of the main processes on page 84 [cf. Key considerations], where the details of the component of a Knowledge System is set out in sub-sections 3.2.1 to 3.2.15. These fifteen processes are grouped under the three main processes of knowledge creation, knowledge dissemination and knowledge utilisation, as outlined in Figure 3.1 as follows:

Having discussed the KM processes, and outlined the requirements for the development of a KM system, the author then will reviews the literature on the functions of KM. This is done in section 3.3. Here the researcher shall discuss the five fundamental functions for the development of a realistic KM system are discussed. These being: gather; organise; search, distribute, and deliver; collaborate; and refine. These components are the building blocks of any KM system, sub-section 3.3.1. In sub-section 3.3.2 the various KM roles in the organisation are identified and discussed. Here one shall identify nine such roles from the literature are identified: consultants, teachers, librarians, reporters, editors, oracles, critics, bards, and village gossips. The need for a properly specified KM system cannot be over-emphasized, but nevertheless, the definition of the roles of such systems must have some basic functionality. This is the brief of the section. Sub-section 3.3.3 deals briefly with the rules, and specification of a KM system. The present chapter looks at the four functional criteria for the classification of a KM system, as proposed by Jackson (1998), in sub-section 3.3.4. The chapter will then conclude by addressing the concept of the knowledge plan in section 3.4.

KM Processes

From Chapter 2 one may arrive at a realisation that knowledge can transform an organisation by moving it into new areas of activity [Stadler, 1999; Heavens G. Knapps, 1999]. In support of this view, is the research question of the present study, Chapter 1, section 1.1.1 which seeks to find out “how are KM strategies enabled by the support of asynchronous groupware (AG) systems?” is against the background that KM strategies have been found to follow a process. For a clearer understanding of this process, it would seems that from the evidence at hand that any definition of the components of knowledge requires the articulation of knowledge in two ways: “the degree to which it is codified and the degree to which it is distributed.” [Hall, and Andriani, 1999:45].

The analysis to follow will use the term KM in this research to mean “. . . the practice of adding actionable value to information by capturing, filtering, synthesizing, summarising, storing, re-trieving and disseminating tangible and intangible knowledge. [It also covers the development] of customised profiles of knowledge for individuals so they can get at the kind of information they need when they need it. [Additionally, this includes] creating an interactive learning environment where people transfer and share what they know and apply it to create new knowledge.” [Wah, 1999:16]

In this regard, KM is viewed as a process. It is the process through which organisations create and use their institutional or collective knowledge. It has three sub-processes:

Organisational learning – the process through which the organisation acquires information and/or knowledge;

Knowledge production – the process that transforms and integrates raw information into knowledge which in turn creates BI, and is useful to solve business problems, and;

Knowledge distribution – the process that allows members of the organisation to access and use the collective knowledge – corporate memory of the organisation.

The question one may ask is how does this inform the concept of a knowledge system? In the context of the present study, a ‘knowledge system’, means the web of processes, behaviour and tools which enables the organisation to develop and apply knowledge to its business processes. It includes the infrastructure for implementing the KM process. There are usually two components here:

Firstly, there is a robust IT infrastructure (database, computer networks, and software). The study is not advocating just a good or popular relational database, or a sophisticated groupware, or email system.

Secondly, there must be an organisational infrastructure. This includes the soft characteristics of the system. There are incentives schemes, organisational culture, critical people and teams which are involved in the KM sub-processes. This also accounts for, most importantly, the internal rules that govern these sub-processes.

In this framework, one should think of data as information devoid of context. Information is data in context, while knowledge is information with causal links. So within the logic of the knowledge system, the more structure that is added to a pool of information, the easier it will be for one to achieve the benefits of a knowledge system – see the portal of the model [cf. Figure 9.1 KM – BI Model].

In this regard, the definition of a meaningful KM initiative should be aligned to the enterprise strategy. This would therefore mean the development of formal KM strategies, from which realistic and concrete goals can be derived. Hall and Andriani [Hall, R. and Andriani, P., 1999:45] identified four types, or states of knowledge, which may be used in deriving such an alignment of corporate strategies with KM projects. These are:

Undistributed tacit knowledge: ‘personal knowledge’;

undistributed explicit knowledge: ‘specialising’;

distributed explicit knowledge: ‘protocols’;

distributed tacit knowledge: ‘embedded’, and

routines. [Hall, and Andriani 1999:45].

The secondary research question, in this thesis, is concerned with ‘how can organisations success-fully implement knowledge management projects and practices?’ [cf. 1.2.3]. The formulation of a KM strategic framework, whether to a limited scope or informally, should nevertheless be made in order for the enterprise to successfully manage the processes involved in knowledge creation. Insights on how these processes may be used to manage knowledge projects and initiatives are evidenced by Hall and Andriani [1999:46]:

Tacit knowledge may be ‘externalised’ by maintaining a record, or inventing a code – Ravel2 writing his manuscript;

Codified knowledge may be ‘distributed’ in books, by intranets and extranets, etc. – Ravel’s publisher distributing his sheet music;

Explicit knowledge may be ‘internalised’ by a process of learning by doing; when this has been successfully achieved the knowledge has become second nature, for example, an expert musician playing Bolero3 without sheet music;

Tacit knowledge may be communicated and enhanced by a process of ‘socialisation’ which involves shared experiences – for example the author, who cannot read music, (my life’s goal, though, is to be able to do so) can nevertheless acquire knowledge of Bolero by hearing it may times;

Substitutive knowledge may replace old knowledge that has to be unlearned; this is de-scribed as ‘discontinuous learning’ – for example moving from a western musical conven-tion to an eastern musical convention. This can be a painful process if the old knowledge that has to be discarded represents a significant personal investment [Hall, and Andriani, 1999:46]).

The understanding of these processes and how they are implemented is the basis for a knowledge definition protocol. The knowledge definition protocol sets the foundation for the formulation of the goals and strategies for the development of projects and the effective management of those projects. The knowledge definition protocols will also serve to explain varying expectations that project managers have, and differing interpretations of the procedures and scope of the knowledge management projects. Proper definition will prevent contradictory concepts from a very early stage in the KM project life cycle. During this life cycle, project managers may return to the protocols of the knowledge requirements to ascertain which methods and technologies were identified for use within the knowledge spectrum. Project evaluation and assessment are attained; in that, from time to time, the defined knowledge practices and protocols may be reviewed.

The literature differentiates between knowledge practices on the normative, the strategic and the operational level. There is a close relationship between these practices and the processes of knowledge in regard to knowledge:

Saltar Bawang asserts,

. . knowledge management is a multifaceted discipline that requires culture, process and technology to work together on a large scale. As a result, knowledge management is an evolutionary path for almost all companies. [Bawang, 2000:38]

In this knowledge process framework he, Saltar Bawang, identified five key elements of the knowledge management process, which organisations must follow in order to create a sustainable competitive advantage for the future. Our secondary research question as framed, earlier on, in this chapter and Chapter 1, section 1.2.3 was asked to seek answers as to the metrics behind these elements, with goals to:

Provide the firm with all the necessary knowledge regarding its industry, business, eco-nomic and competitive environment on a continuous basis;

assist in the formulation of competitive strategies that successfully positions them for the future;

assist in creating an appropriate business, organisation and information system design that integrates and complements their strategic direction;

assist in the implementation of their strategic and operational plans, and

develop a methodology to monitor and examine their progress and enable them to quickly respond to changes in the business environment [Bawang, 2000:3].

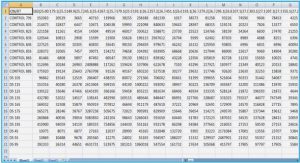

In the next fifteen sections: 3.2.1 to 3.2.15, these processes as tabulated in Table 3.1, are discussed in more detail..

Knowledge Identification

Knowledge identification is not necessarily detecting knowledge that is already available in the firm’s information inventory. This process will often require both the use of data processing systems and will also require the assistance of people with specialised and technical expertise. In particular, statistical methods and artificial intelligence can be used to identify measure, evaluate and harvest the requisite knowledge of an organisation.

Knowledge identification differs from data mining on the one hand; identification of knowledge is not only concerned with the management of data, which are of crucial importance to organisa-tions. On the other hand, knowledge identification does include, to a large extent, the technical aspects of classical data mining and the automated extraction of knowledge from text and other data and information sources.

Knowledge Development

Knowledge development involves not only the functions of knowledge production in the formal sense of the concept of the development of a process or a product or service for consumption in terms of the commercial milieu, but it also includes the performance metrics of an organisation. This is in the context that KM ”is a conscious strategy of getting the right knowledge to the right people at the right time and helping people share and put information into action in ways that strive to improve organisation performance and achieve the organisational objectives” [Bawang, 2000: 40].

The present investigation is not saying that the development of knowledge development and knowledge creation initiatives, in the physical sense, in the organisation’s R and D department is not important. One is arguing that the processes used in the investigation and communication of that knowledge is more important than in the context of product creation and production. The generation of new ideas, abilities and products (of course) must be considered in addition to the other innovative processes of the enterprise. A central role of knowledge development is the promotion of creativity and communication among employees through the integration of enabling knowledge sharing strategies and an appropriate collaboration framework.

The presence of an appropriate organisational culture is a prerequisite for successful knowledge development. The analogy is like the role played by technological devices and tools within the spectra from telephones and whiteboards, to videoconferences and groupware, but more specifically asynchronous groupware.

Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) argue that knowledge development is based on the interaction of implicit and explicit knowledge as the basis for the generation of new knowledge. Also, from the literature, Ikujiro Nonaka specified a model for organisational knowledge development, which he calls the spiral of knowledge in his article in the Harvard Business Review ‘The knowledge creating company’ [Nonaka, 1991]. This model will be presented in Figure 3.5, section 3.7.

Knowledge Acquisition

In contrast to knowledge development is the process of knowledge acquisition, which looks at the integration of external knowledge in the enterprise. This integration is by means of recruiting knowledge workers, specialists with particular value adding expertise, who usually bring relevant experience to the enterprise to assist it to meet its strategic objectives. The period over which this method of knowledge acquisition is used can be for different life cycles, ranging from permanent to project specific duration.

Knowledge Sharing

Apart from the development of new knowledge in the enterprise and the acquisition of knowledge from external sources, the knowledge that employees already have should not be ignored. In practice it is found that most employees find it rather difficult to share their knowledge with each other. The problem is due in part to the nature of the organisational culture, or sometimes, to the modes of operation, in terms of how they synchronize with or co-ordinate with the KM efforts.

If employees espouse the “knowledge is power” mentality, then, there will be a conflict between their personal interests and the interests of the enterprise in knowledge sharing. An organisa-tional structure, which is favourable for sharing knowledge, must develop a perspective, which does not let this conflict grow out of control. Knowledge sharing must be understood as a nat-ural part of the organisation business (work), and strategic landscape, in the development of a KM strategy.

On the part of management, it should not only be through lip service but there should be com-mitment to the KM strategy. It cannot be expected that employees will share their knowledge, if, say, the time, which is needed for it, is evaluated as being unproductive. The management has to, therefore, make provisions in the organisational basic conditions of operations in order to accommodate this cultural change. The approach will be one that begins with the basic conditions, which provides for the individual employee to have the requisite time for sharing his knowledge, and also where necessary the introduction of not-financial incentive systems as motivation for knowledge sharing.

It is to be understood that knowledge sharing is not only achieved through direct communication. It may take place over a cup of coffee or in a formal session. The concern here is when it takes place where employees enter the knowledge in an information system. A substantial aspect for the motivation of employees to use the system depends on the efficiency and the user friendliness of this system.

Knowledge Entry

The acquisition of knowledge from external sources can be entered in a knowledge repository, in order that the organisation may have centralised access to it. A part of this work can take place without the participation of many employees through available information inventories in the repository one operates, which becomes embedded into context knowledge; that would be a direct form of integrated knowledge development and knowledge entry in the repository.

This usually requires the capturing of information and corporate memory from the knowledge within the organisation. This knowledge may be either structured or unstructured. The unstruc-tured knowledge may take the form of the contents of discussion or idea which are generated from employees’ interactions, while the structured form of knowledge may take the form of mar-keting reports or customer profiles. Additionally, the integration is aimed at knowledge from external sources, as soon as, it becomes accessible to the organisation.

The entry of knowledge into the enterprise may be through employees themselves in an informal manner, or it may be by way of a formal and structured process using a specially designated officer whose responsibility it is to harvest and capture organisational knowledge and BI (i.e. corporate memory).

A prerequisite for a successful knowledge harvesting programme is one which is driven by the latent barriers to knowledge sharing will be managed and co-ordinated by them. The role of the enterprise in this process is paramount to the very success of such a programme. If the enterprise does not recognise and reward the performance of employees for their participation in this process, the input of its knowledge into the system (the knowledge responsibility) the whole process will most likely fail. The responsibility will have no future. The ideal integration process of knowledge harvesting with the other business processes of the enterprise should be one where the involvement of employees are viewed as a normal part of the business of the organisation.

The decision is to be made between the knowledge that one would like to enter, and the knowl-edge whose entry would in the long run be considered uneconomic, must also be considered in connection with the decisions in terms of the filter mechanisms being used. The organisations must also decide which types of knowledge provide the highest potential value in terms of mea-suring the degree of employees’ participation in the process of knowledge harvesting. Likewise, the decision must be made to determine, which knowledge is to be harvested, if possible, in real time, and that which is not so time critical.

Table of Contents

Declaration

Abstract

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

Glossary

I Introduction 1

1 Introduction 2

1.1 Research Motivation

1.2 Research Objectives Hypothesis and Supporting Literature

1.3 KM Strategic Requirements

1.4 Research Method

1.5 Thesis Overview

2 Knowledge Management

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Definitions of Knowledge Management

2.3 Implicit Knowledge

2.4 Intellectual Capital

2.5 The Hierarchical Aspects

2.6 Knowledge Management – An Overview

2.7 Aims of KM

2.8 Summary

3 Knowledge Management Strategies

3.1 Introduction

3.2 KM Processes

3.3 Functions

3.4 The Knowledge Plan

3.5 Reshaping Competition KM

3.6 Technologies

3.7 The Knowledge Journey

3.8 Summary

4 Asynchronous Groupware

4.1 Introduction

4.2 Taxonomies for groupware

4.3 AG : An analysis of pros and cons

4.4 Workgroup Computing

4.5 Workflow Systems

4.6 The case for AG research on KM groups

4.7 Summary

II Research Question and Methodology

5 The Research Question

5.1 Introduction

5.2 The research approach and strategy

5.3 Exploratory Survey

5.4 Summary

6 The Research Methodology

6.1 Introduction

6.2 Sampling frame

6.3 Sampling technique

6.4 Statistical analysis models

6.5 Other Considerations

6.6 The KMP survey

6.7 Summary

III Research Results

7 Findings and Results I

7.1 Introduction

7.2 Exploratory factor analysis

7.3 Findings on KM Practices

7.4 Hypothesis testing

7.5 Summary

8 Findings and Results II

8.1 Introduction

8.2 Factor Structure

8.3 KM Practices and Strategies

8.4 Reasons Knowledge Management Practices were adopted

8.5 Asynchronous Groupware

8.6 Other statistical tests and analyses

8.7 Summary

9 Evaluation

9.1 Introduction

9.2 Hypothesized path analytic structure

9.3 Instrument Assessment (Validity and Reliability)

9.4 The Measurement Model

9.5 The Structural Model

9.6 Summary

10 Results From An Iteration Of The Action Research Cycle At Directorate

10.1 Introduction

10.2 Diagnosing

10.3 Action Planning

10.4 Action taking

10.5 Evaluating

10.6 Summary

IV Discussion of Results and Conclusion

11 Conclusion

11.1 Introduction

11.2 The research motivation

11.3 General summary of the research

11.4 Contribution of this research

11.5 Implications and recommendations

11.6 Limitations

11.7 Future Research

11.8 Conclusion

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT