Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Water Services Providers (WSPs)

The Strategic Framework for Water Services defines a Water Service Provider as:

– Any person who has a contract with a WSA or another WSP to sell water to and/or to accept wastewater from that authority or provider, these are defined as bulk water services providers.

– Any person who has a contract with a WSA to assume operational responsibility for providing water services to one or more consumers (end users) they are defined as retail water services providers.

– A Water Services Authority that provides either or both of the above services itself.

A WSP can be either local (WSPs who provide water and/or sanitation to only one water services authority) or regional (WSPs who operate infrastructures crossing water services authorities boundaries). They can be public organisations (municipality, water board), community organisations (such as Community Based Organisations (CBOs11)), private or mixed organisations.

The current national situation of water service provision is highly fragmented with a high number and various legal statuses of water service institutions acting as WSPs. In some municipalities acting as WSAs, notably in former homelands, domestic water services providers have not been identified yet. This was common within the research area. One of the aims of the water policy since 1997 is precisely to simplify and make this situation clearer. The Strategic Framework for Water Services proposes some simplifications that might not be applied yet:

– A single consumer interface: a consumer should deal with one retail water service provider and only one retail sanitation service provider (the best would be one provider for both services).

– A single contractual interface: the WSA should have only one contract with one WSP in a specific area within its jurisdiction. Moreover, a contract should be geographically defined and there should not be any overlap between WSPs.

– A single chain of contracts: it is important that a single chain of contracts ensure the effective delivery of water from the resource to the consumer, and treatment of wastewater from the consumer to the resource.

As they bear operational responsibility, WSPs also carry out duties, starting with providing water services in accordance with the Water Services Act and by-laws setting by Water Services Authorities:

– Domestic water must be provided in an efficient and effective manner.

– WSPs must assume the operational and financial risk related to the provision of water and sanitation services and the collection of fees. Only in a case where CBOs perform water service provision, could WSA assume part of the financial risk related to the provision of services.

– WSPs have to publish a consumer charter approved by the WSA that includes duties and responsibilities of both WSP and consumers.

– Since the SFWS, all WSPs must provide a business plan, which is an annual operational plan including technical, investment, financial and social12 plans.

According to the Water Services Act, each WSP must give information on the tariffs implemented, the number and socio-economic condition of people they serve and the level of services provided (via the Business Plan for example) to the WSA having jurisdiction in its area of provision, the relevant province, DWAF or any consumer or potential consumer.

Principles and objectives of water tariff setting in South Africa

As we saw in the section 1.2.2.1, the access to water and to a healthy and non-harmful environment is a basic right in South Africa. In this context, water pricing should not jeopardise this right and should promote access to an adequate amount of clean potable water (Eberhard, R., 1999).

The Strategic Framework for Water Services (DWAF, 2003) defines retail water tariff principles as follows:

– Tariffs should be applied equitably and fairly (equity objective).

– The amount individual users pay for services should be in proportion to their use of that service (which means that it should depend on the level of service and of the volume consumed).

– Water and sanitation tariffs should seek to ensure that a minimum basic level of water supply and sanitation service is affordable for all households […] (a principle we can interpret as an affordability objective).

– Tariffs must reflect all of the costs reasonably associated with rendering the service (which means the payment from consumers should recover the costs of running the networks, which we can interpret as at least operation and maintenance costs).

– Tariffs must be set at levels that ensure the financial sustainability of the service, taking into account subsidisation from sources other than the service concerned (global income -including subsidies, cross-subsidies, loan and water fees- should recover all the financial costs -capital, administrative, replacement, O&M costs and cost of servicing capital-).

– The economical, efficient and effective use of resources, reduction of leaks and unaccounted-for water, recycling of water, and other appropriate environmental objectives must be encouraged (this principle is close to the resource conservation objective).

– A tariff policy may differentiate between different categories of users, debtors, service providers, services, service standards, geographical areas and other matters as long as the differentiation does not amount to unfair discrimination (all users and providers will not pay or charge the same amount, but only if it is justified -for example in case of different level of services or water scarcity- and does not contradict the previous principles).

– All forms of subsidies should be transparent and fully disclosed (this statement aims at preventing corruption; it also implies a clear monitoring of water accounting systems.

We should note that DWAF, in “Norms and Standards in Respect of Tariffs for Water Services in Terms of Section 10 of the Water Services Act” (DWAF, 2001), is much more specific. Indeed, this text specifies that any WSA is obliged to differentiate tariffs according to levels of service (communal stand, private controlled water services (taps in dwelling or in the yard with a meter), private uncontrolled water services (taps in dwelling or in the yard without a meter), sanitation connected to a sewer, sanitation non-connected to a sewer).

The same text advises the use of an increasing block tariff of at least 3 blocks, with the lowest block of a maximum consumption of 6m3 with the lowest amount (including a zero amount), and the highest as high enough to discourage water wastage. It also asserts that a connection fee should be charged.

In the SFWS principles we find the objectives stated in the previous section (with the exception of the economic efficiency objective). In the following part of the study, via the survey of Water Services Authorities we will try to estimate to what extent the water pricing policies in the study area attain these objectives.

Water tariffs implemented in South Africa

Water tariffs in South Africa vary. The most complicated are generally found in urban areas. In rural areas, pricing systems are often simpler and in some places, especially in former homelands there is no billing yet, cultivating a non-payment culture. Moreover, this non-payment culture was heavily promoted in the last years of apartheid as a means of opposing the government.

It is not possible to give a general description of a rural reference tariff as water pricing practices vary from scheme to scheme, but examples of tariffs can be given.

According to a WRC14 report (Cost and tariff model for rural water supply schemes, (Still, D. et al., 2003)) that surveyed 38 water services projects in South Africa, the flat rate monthly payment system is the most popular water pricing option (employed by 31 projects). For these cases, the mean flat rate was R9.47/household/month, with an interval of R4 to R16. However, another WRC report asserts that a flat rate can lead to inequity and conflict (Marah, L. et al., 2004). Indeed, large family are more likely to use more water than smaller ones. Small families are therefore less inclined to pay diligently. Such inequities were identified as a factor in non-payment by the poor in some case studies (including some in Limpopo Province). In the projects where water rates were being charged at a metered rate, the mean rate was R6.33/m3, with a standard deviation of R2.36/m3.

Another WRC study (Ralo, T. et al., 2000) at household level in the rural areas of the Eastern Cape (the poorest province of South Africa) shows that 144 households, nearly half of all respondents consider they cannot afford an average tariff of R8.18 per month. A DWAF report (DWAF, 1998) gives example of rural water tariffs that range from R1.4/household/month to R15/household/month.

Water pricing implementation alone does not constitute a services pricing policy. Compensatory measures (subsidy mechanisms) are also an integral part, especially to meet the affordability objective. The following section will present subsidies’ diversity and implications.

Subsidies: how to choose the right subsidy to reach the right target

From the literature on this subject, some specific criteria can determine the design of a subsidy system (Lemenager, M., 2004):

– Justified need: this is quite difficult to assess. The main tools commonly used for this purpose are willingness to pay studies.

– Precise identification of beneficiaries: this point is often difficult to reach, because surveys and census design a subsidy system based on one specific moment.

– Low administrative costs: unfortunately, it is generally very expensive to identify the correct beneficiaries of a subsidy.

– No perverse incentive: the injection of subsidies comes into conflict with the objective of economic efficiency. For this, it is better not to deliver the total subsidy to avoid waste and only for a short period and for an amount high enough, in order to avoid a population passivity risk (risk of dependence on a subsidy or poverty trap). Such policies do not incite a community to participate to services costs and sustainability and to their own development.

Secondary objectives can also be quoted. Subsidies should be realistic, adapted to the targeted groups, transparent and regressive in order to permit a switch to a higher tariff.

Subsidies should focus on connection, in order to reduce the initial cost rather than decrease expenses linked to existing users.

Types of subsidy mechanisms

Various types of subsidy mechanisms can be identified: Budget subsidies (from government or external institution). They are “traditional” mechanisms where the subsidy reaches the general operating budget, in order for it to settle tariffs below costs. This system has drawbacks, as it does not permit easy control of the operator’s management and does not involve any targeting (all users will benefit from this subsidy).

Direct subsidies. They are injected directly to specific users. They aim at making the poor the same customers as the others (increase their purchasing power to catch up of demand).

Cross subsidies. They express solidarity between water users. Tariff (IBT) or unifying surtax (1 or 2% of the total invoice) permits this type of subsidy. Their advantages are that they do not appeal to exterior resources (which are sometimes uncertain) and permit a selective targeted distribution. However, a cross-subsidy is only efficient in the case where there is a sufficient proportion of wealthy users.

How does one know the good target is reached?

A key consideration in evaluating the efficacy of a subsidy policy is measuring to what extent they succeed in reaching the poorest part of the population (Foster, V. et al., 2003). Analysis of a subsidy targeting system is commonly done according to two standard indicators.

Error of inclusion arises when people who are not poor benefit from the subsidy. The following diagram (Fig. 11) helps to illustrate the meaning of this term. The error is defined as the percentage of the subsidy beneficiaries who are not poor (EI=BNP/B). Errors of inclusion are essentially a form of inefficiency, because they represent a leakage of funds.

Table of contents :

1 Context of the study

1.1 Description of the study area

1.1.1 Physical description of the Olifants River Basin

1.1.1.1 Location

1.1.1.2 Climate and hydrology

1.1.2 Socio-economic overview of the Olifants River Basin

1.1.2.1 Population

1.1.2.2 Economic situation

1.1.2.3 Water supply infrastructure

1.2 Institutional setting of domestic water services in South Africa

1.2.1 The apartheid era

1.2.1.1 Apartheid history in short

1.2.1.2 Key principles of the status of water

1.2.1.3 Water services before 1994

1.2.2 Water services sector after the apartheid

1.2.2.1 Key principles of the new water policy

1.2.2.2 Main actors of the water services sector

2 Problematic

2.1 Objectives of a water pricing and subsidy system to improve access to water for lowincome population

2.2 Domestic water pricing systems: diversity, advantages and drawbacks

2.2.1 Types of domestic water pricing

2.2.1.1 Monomial pricing structures

2.2.1.2 Two-parts pricing structures

2.2.1.3 Other types of tariffs

2.2.1.4 Connections fees

2.2.2 Domestic water tariff in South Africa

2.2.2.1 Principles and objectives of water tariff setting in South Africa

2.2.2.2 Water tariffs implemented in South Africa

2.3 Subsidies: how to choose the right subsidy to reach the right target

2.3.1 Objectives and diversity of subsidies

2.3.1.1 Key objectives of a subsidy system

2.3.1.2 Types of subsidy mechanisms

2.3.1.3 How does one know the good target is reached?

2.3.2 Subsidies in South African water services

2.3.2.1 Subsidy policy principles in South Africa

2.3.2.2 Main subsidies encountered in the South-African domestic water sector

2.4 Cost recovery in South Africa

2.4.1 Cost-recovery issue in developing countries

2.4.1.1 Cost recovery: a controversial issue

2.4.1.2 How to define cost-recovery?

2.4.1.3 Major issues concerning cost recovery

2.4.2 The issue of cost-recovery for water services in South Africa CemOA : archive ouverte d’Irstea / Cemagref

3 Methodology

3.1 First step: meeting with national stakeholders and literature review

3.2 Choice of a level of analysis

3.2.1 The first option: a survey at ward level

3.2.1.1 Methodology justification

3.2.1.2 Drawbacks

3.2.1.3 Principle and construction of the stratified random sampling

3.2.2 Reasons of a change in methodology

3.3 A survey at water services authorities level

3.3.1 Identification of interviewees

3.3.2 Questionnaire construction

3.3.3 Data analysis

3.3.4 Methodology justification

3.3.5 Drawbacks

4 Results

4.1 The institutional context of domestic water sector: from theory to reality

4.2 Analysis of the survey at Water Services Authority level analysis

4.2.1 Socio-economical characteristics of the WSAs

4.2.1.1 Population

4.2.1.2 Access to water & sanitation

4.2.2 Institutional organisation of the water sector

4.2.3 Domestic water pricing policy diversity

4.2.3.1 Subsidies

4.2.3.2 Water tariffs

4.2.3.3 Free Basic Water policy

4.2.3.4 Investments and conclusion on financial information

4.2.4 General issues

4.2.4.1 Difficulties in domestic water services management

4.2.4.2 Multiple-use of domestic water

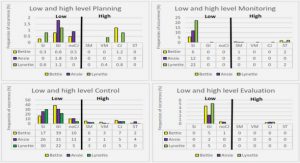

4.2.5 Water policies relevance regarding key-objectives

4.2.5.1 Water pricing policies regarding the key-objectives

4.2.5.2 Global assessment of the water pricing policies in surveyed WSAs

4.3 Information on networks

4.3.1 Networks presentation

4.3.1.1 Age of schemes

4.3.1.2 Population-related information

4.3.1.3 Source of water

4.3.1.4 Storage capacity

4.3.1.5 Water treatment work and sewage treatment work

4.3.1.6 Boreholes

4.3.1.7 Financial data

4.3.2 Data analysis

4.3.2.1 Heterogeneous set of data

4.3.2.2 Building a typology

Conclusion

References