Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Methodology

This section will introduce the research methods that this study made use of, what part they play in the greater whole, as well as the fundamental limitations of the study and each form of data collection.

This study employed inductive research (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2007) to gain an overview of students’ attitudes towards relationship marketing on online social networks.

For the purpose of this study the consumer is to be considered the unit of analysis (Saun-ders et al, 2007), and the types of organizations and industries used during the research is intended purely as examples to simplify data collection. This study was conducted over a short period of time (3 months) and is cross-sectional in nature.

The study is mixed method in nature, and employs both quantitative and qualitative re-search methods. The survey described in 3.1 allows respondents to answer multiple-choice questions and was analyzed quantitatively. The focus group study described in 3.2 was en-tirely qualitative in nature. Mixed method research aims to utilize the objectivity and reli-ability of quantitative research with the explanatory strength of qualitative methods (Ta-shakkori & Teddlie, 2003).

Mixed methods are particularly suited for inductive research, where quantitative and quali-tative data can be used interdependently to generate explanations for patterns that occur, care must however be taken to avoid subjectivity (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004). The mixed method approach that is utilized is essentially a form of cross-methods triangulation (Jick, 1979), where multiple methods are used to verify whether similar conclusions are reached. While the sample groups for the two research methods employed were not identi-cal, the majority of focus group respondents participated in the survey study.

Online social networks have a high degree of market penetration in the university setting worldwide (Gross & Acquisti, 2005), which allows access to a sample group that reflect a very large part of the overall population that are users of these networks. Previous research was used to formulate a survey that attempts to explore the different dimensions of the problem. The survey was distributed to students across multiple university faculties.

Prior to reaching the final conclusions a focus group was conducted in order to discuss the findings with an audience that were not biased from having conducted research in the area. The focus group was carried out in order to prevent fundamental errors that can arise from misunderstandings and questions that were unintentionally flawed, or from contamination due to factors such as bias towards socially desirable answers (Dillman, 2000). Focus groups are multi-participant studies that make use of group interaction to gather data and reach conclusions (Kitzinger, 1994).

Survey

The aim of the survey was to gather descriptive primary data towards answering the re-search questions. It targeted university students’ belonging to faculties represented at Jönköping University and made inquires about past experiences of online social networks and attitudes towards relationship marketing efforts on these networks. Due to the high degree of market penetration in the targeted setting and the purpose of this report, respon-dents that did not use online social networks were considered non-respondents. These re-spondents made up less than 5% of the survey respondents. It was important to filter out these respondents since having them answer the survey without the proper knowledge about the networks results in unwanted results since the remainder of the survey assumed that the subject did use one or more of these networks.

The survey design was based on similar research conducted by a host of other researchers and covers a relatively broad set of variables for analyzing consumer perception of relation-ship marketing on online social networks.

Survey Design

The survey was designed as a self-administered questionnaire (Saunders et al., 2007) deliv-ered in a classroom setting. This method had the benefit of distribution to a high number of respondents, primarily because classroom norms tend to prohibit students from leaving the room before the survey had been completed by their peers. This had the benefit of re-ducing respondent bias, where the students who happen to be interested in the subject were the one’s responding to the survey.

The available time frame for administering each survey was limited, because of each survey session being conducted during classroom time with people that have other obligations. The time required to answer the survey was therefore limited to 10 minutes or less, and with questions designed with simplicity that was in line with this time frame. The survey made extensive use of multiple choice questions to allow for this.

The survey was designed to cover three general areas: general sample attributes as well as usage patterns and adopter motivation of relationship marketing on online social networks. The third area of interest in this study, relationship continuance drivers, was primarily stud-ied qualitatively through the focus group study.

General Attributes

Research within this area of study tends to make use of attributes that divide the sample in-to smaller but significant groups. Gross & Acquisti (2005) used gender as an attribute in their research, and it is likely to be one of the most commonly used variables overall since it is of relevance in such an enormous range of fields. Joinson (2008) used age as an attrib-ute variable in his research on use of Facebook, and it is another commonly used variable for data analysis. Etter & Perneger (1997) found that both these variables tend to be linked to non-response biases, and care must be taken to avoid this form of bias.

Usage Patterns

McKenna & Bargh (1999) used amount of online activity as a behavioral variable in her re-search on online social networks and found that it explained differences in attitudes and behavior. This variable was included because users who spend large amounts of time online are also likely to be open to performing more actions online, such as communicating with companies. This category of variables also includes questions about which form of services users would be willing to perform online in the near future.

Eccleston & Griseri (2008) based a large part of their research on simple binary behavioral variables involving past and current actions, such as whether a user had previously at-tempted to convince others to purchase a product. Similar variables can be used to deter-mine whether users are currently maintaining relationships with any commercial organiza-tions on online social networks, and whether they had attempted to convince a friend to join.

Online social networks have a rich culture of passing messages forward, and this dimension is included in the study because it is one of the key ways organizations can generate aware-ness of their presence within the networks. Dobele et al. (2007) argued that the motivation to pass information forward tends to be triggered by different sets of emotions. For exam-ple, a user may choose to invite a friend to an open user group based around an amusing video, or an event that makes him or her angry.

Adopter Motivation

Kotler et al. (2005) discussed the issues of the consumer value in relationship marketing, in particular that the consumer must be interested in obtaining some benefit from engaging in relationships with companies. The survey incorporates this by asking about the benefits the adopters were interested in, and from which types of organizations. Wiseman (1972) ar-gued that opinion variables tend to be easily contaminated by improper use of methods, and great care must be taken to avoid questions leading the respondent to one of the alter-natives in a question.

The survey made use of this concept in addition to the Viral Marketing Framework sug-gested by Subramani & Rajagopalan (2003), which is based on the idea that users have dif-ferent motives for passing on messages and recommending others to join networks – both selfish and altruistic. These factors were implemented into the survey by inquiring about vi-ral behavior and underlying motivations.

Sample Selection

The sample group the survey was administered to was selected among students at Jönköping University in November 2009. The study was conducted at the beginning of in-class sessions at the engineering, business and teaching faculties with the cooperation of the professors hosting the lectures. This context has the benefit of reducing nonresponse bias based on interest, because the students have no incentive such as time constraints to de-cline to answer the survey. Armstrong & Overton (1997) argue that the most efficient way of avoiding nonresponse bias is to avoid or reduce nonresponse, this has been avoided by administering the survey in an in-class setting.

To allow for high diversity in gender and faculty representation stratified random sampling was used (Patton, 1990) to select classes to attend and conduct the survey at. The strata cri-teria used was hosting faculty, and the survey contains responses from four randomly se-lected lectures at the different faculties. This form of purposeful sampling allows research-ers to reduce the risk of creating a sample that is not representative for the population (Saunders et al., 2007). The engineering faculty at Jönköping University is highly dominated by male students, while the teaching and business faculties have some overrepresentation by female students. Using hosting faculty as sampling criteria therefore allows for a sample that has an even gender balance, without polluting the sample by limiting it to one particu-lar faculty or program.

There were a total of 195 respondents, 95 males, 100 females, with an additional 7 non-respondents (not included in the total). 38 of the respondents were from the engineering faculty, 73 were from the education and communication faculty and 84 were from the business and economics faculty. The student groups primarily consisted of Swedish stu-dents, with a small amount of international students.

Data Quality

The non-response rate of the survey study was less than 5% of the total surveys adminis-tered, which should be considered to be very low. This primarily stems from the setting the survey was administered in, and reduces the risk of non-response bias (Saunders et al., 2007).

In quantitative research care must be taken to ensure validity. Given the descriptive nature of this survey the primary issue is external validity, to which degree it is possible to apply the results and conclusions drawn from one group or sample on the full population or on other specific groups (Calder, Phillips & Tybout, 1982). The sample drawn from Jönköping University is likely to be transferable to students in Sweden in general, and is likely to be applicable to other student bodies in similar cultural contexts.

Another issue in research with pre-defined answers is ‘meaning units’, which in the context of the survey would be an alternative on a multiple choice question. When a meaning unit is too broad and fragmented, the conclusions drawn from are likely to be weak (Graneheim Lundman, 2003). The problem of fragmentation in the survey has been reduced by hav-ing a relatively large amount of alternatives as well as the option of providing open-ended input.

It is unlikely to be applicable on the full general population, but may have limited applica-bility on early adopter groups that share student adoption patterns. This study is aimed at determining attitudes of users of these networks, and at present these networks are popu-lated primarily by people in similar age groups as students. The conclusions are therefore expected to apply to young adult users of online social networks in general.

With the great amount of students (i.e. people of age 18-25) in the online social network population (Gross & Acquisti, 2005), the sample was proposed to be sufficiently accurate in terms of sample size to have a high degree of validity.

Pilot Study

An inherent weakness in any form of questionnaire is that the researchers who designed it tend to possess a much higher degree of knowledge in the subject than the respondents, as well as an awareness of what it is that the study in question aims to determine. Therefore it is important to attempt to minimize the risk of formulating questions that are either am-biguous, unclear or self-answering (Saunders et al., 2007).

Bell (2005) recommends all researchers to perform a pilot study before finalizing the survey design and layout, to attempt to weed out these errors. A pilot study is conducted by letting a limited amount of respondents answer the survey and use their performance as feedback towards the survey design. In some instances the respondents will simply ask the researcher administering the survey to clarify a question or statement, but Fink (2003) argues that re-searchers should also look through the answers given and see whether all instructions were carried out properly.

A pilot study was performed by allowing a handful of individuals in a university setting to complete the survey while being allowed to ask the person administering the survey any questions they may have. These individuals were selected from people with various knowl-edge in social networks and had vastly different levels of familiarity with the concepts the survey concerns. Following this pilot study certain questions were reformulated especially in regards to age distributions and number ranges, but in general the respondents were able to complete the survey with relative ease.

Because this study is conducted in English, the survey was conducted in the same language. While providing a translated survey was an option, this would have run the risk of con-taminating the sample. Questions worded in English may not carry the exact same meaning or weight as one worded in Swedish would. During the pilot study it was found that some respondents had issues with properly understanding question 10. The wording of question 10 was therefore simplified in order to avoid this in the real sample.

Certain respondents had problems understanding questions that involved language outside of the general vocabulary, such as terms used to describe online social networks. To pre-vent sample pollution no technical jargon was used in the final survey, and respondents were informed they could ask for translations or explanations at any time. An introductory sentence was also added to the beginning of the survey to introduce the respondent to the subject.

Data Analysis

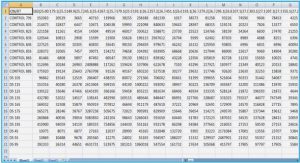

To form a solid set of variables to base the analysis on the software suites SPSS and Micro-soft Excel were used to compile and organize the results of the survey. This form of analy-sis allowed for identifying the most commonly occurring answers, and to identify patterns as well as signs of sample pollution. Multiple-choice questions in particular are suitable for this approach because of their limited range of alternatives. Sample responses were entered as a series of binary variables indicating whether or not any particular answer was selected.

Yin (2003) argues that researchers should attempt to form a theoretical grounding through which to analyze the data prior to its collection. The alternative to this is to attempt to find suitable a theoretical framework in light of the study results, but this brings the issue of creating researcher bias where theories that do not support the study’s conclusion may be ignored.

This study looks at research on relationship marketing and online social networks to form a theoretical framework that acts as a guide when studying the data results. Saunders et al. (2007) argues that even explicit inductive research tends to combine elements of inductive and deductive research, and this study uses a theoretical framework based on previous re-search in attempting to explain the findings, while at the same time acknowledging the pos-sibility of adding additional theoretical background should unexpected data patterns arise. Yin (2003) refers to this form of research as explanation building.

This compiled data was used to find patterns that explain the behavior of users in the ag-gregate sense as well as the differences between them on an individual level. The results of the study were compiled into charts and are presented in section 4, in addition to sample subsets with significantly different answers from the full sample. The data charts were used to gain a graphical overview of the survey data and to form links to previous research. This data was also used to form the agenda for the focus group discussion.

Focus Group

Surveys are limited in the sense that communication tends to be one-way. They do allow for inductive research since patterns may emerge that the initial research did not portray, but they do not allow for discussion, interpretation and general feedback.

To allow for feedback outside of the specific variables that were looked at, a focus group was conducted where discussions on; relationship marketing, social network activities, opt-ing in on marketing activities in online social networks, and forwarding messages to other contacts were carried out. A focus group is essentially a semi-structured multi-participant interview session where any phenomenon or concept can be discussed by outsiders to al-low for new input (Saunders et al., 2007).

A major aspect of focus groups is the benefit derived from interaction between participants and researchers, but also the observation on how participants interact with each other (Car-son, Gilmore, Perry & Gronhaug, 2001). It is a useful tool because it permits new inductive insights based on interaction between those involved in the study when exposed to data that they may or may not relate to.

These focus groups consisted of, at the time of the study, current users of the online net-works in question rather than a random sample of the full population, simply because the topic requires a certain familiarity to discuss.

During these sessions discussions were focused on the findings of the survey analysis and whether the participants believe the results correctly described their behavior. Six major points related to the survey and marketing on social networks were discussed; Marketing on social media, What would make it interesting to join a group, Automatic updates on the news feed, Special offers, Facebook as a discussion forum, and Getting people interested.

The focus group was used to increase the reliability of the study, and to prevent any con-clusions that stem from data that has been compromised by biases and leading questions. The focus groups also provided the ability gain reflections on the results from individuals that did not have a preconceived view of the results.

Focus groups have many other uses, such as generating research questions and objectives, formulating theories and hypotheses, and providing insight into which types of questions are relevant during further stages of the study. The focus group was used for verifying find-ings rather than to generate ideas for survey variables.

Administration

The session was carried out in a study room at Jönköping University with the ability to comfortably accommodate 14 people, refreshments were provided during the session. A dual model focus group was adopted where one researcher made sure the discussion went smoothly and were kept on track, by for example preventing a few individuals from domi-nating the discussions, while another ensured all subjects were covered. The third re-searcher was in charge of note keeping as well as recording equipment and did not take part in the discussions.

Participants were not provided with written material, but were given an introduction to on-line social networks and their associated features that enable relationship marketing to en-sure that every participant had sufficient background knowledge. The session was com-pleted in one hour.

Sample Selection

The focus group consisted of 8 participants, consisting of 6 students who were survey re-spondents and 2 students who were not. The sample was designed to allow for triangula-tion while attempting to prevent sample pollution by limiting the potential for new insight unrelated to the survey. The participants were selected from student volunteers at Jönköping University. The participants were given a gift voucher of 100 SEK at a local bookstore as well as coffee/tea during the session as incentive to participate.

The requirements for attending were limited to being a subscriber to an online social net-work, and both international and Swedish students were chosen to attend. Five participants were native Swedes while three were international students, one from South Africa and two from Germany. Participants were also chosen based on having varied amounts of experi-ence in social networks. There were eight participants during the session in addition to the three moderators, three were male and five were female.

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

1.2 Problem

1.3 Purpose

1.4 Research Questions

1.5 Definitions

1.6 Delimitations

2 Theoretical Framework

2.1 Usage Patterns

2.2 Adopter Motivation

2.3 Relationship Continuance Drivers

3 Methodology

3.1 Survey

3.2 Focus Group

4 Empirical Findings

4.1 Survey Results

4.2 Focus Group Results

5 Analysis

5.1 Usage Patterns

5.2 Adopter Motivation

5.3 Relationship Continuance Drivers

6 Conclusion

7 Discussion and Further Research

References

Appendix

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT

Relationship Marketing in the online social network context: a study on student attitudes