Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Literature Review

Many researchers, including Arai et al. (2011), have attempted to demonstrate how immigrants are represented in the systems built for their protection and security. Focus is especially placed on OECD member countries’ progression in improving immigrant workers’ experiences and perceptions joining the Swedish labour force. Goudarzi et al. (2020) have also expounded on the topic by exploring unemployment rates between immigrants and natives in Sweden. Some researchers, such as Dietz et al., 2015, have also tracked and evaluated employment experience trends among immigrant workers. The study has shown how after the global financial crisis (2007-2009; cited by Chau, Lin & Lin, 2020), the unemployment rate for immigrants within Sweden rose from 3.4 percent to 17.2 percent (Hiyoshi, Kondo & Rostila 2018; p. 1011).

In comparison, the unemployment rate of natives rose to 8.1 percent from 1.4 percent at the beginning of the 21st century (Behtoui, 2008). Research reveals that immigrants’ experiences are worsening and would benefit from inclusivity. As Wilhelmsson’s (2000) research also confirms, immigrants’ chances of finding a job are slim, with a high risk of poor employment relations. Most of the issues surrounding this phenomenon can be associated with various factors that range from economic and social issues. These factors include but are not limited to the high inflation rate that led the country to adjust and enforce severe economic policies surrounding significant changes in fiscal policy reforms, major job cuts, and other related microeconomic policies (Wilhelmsson, 2000).

Sakamoto et al. (2013) also present their argument claiming that Sweden’s labour sector witnessed a cumulative rise in immigrant populations’ employment rates by two percent a year in the last years of the 20th century. This is a strong argument to support the evidence about better inclusivity measures to achieve the goals set out by OECD. The authors have done well in showing Sweden’s determination to acknowledge the problems of unemployment facing immigrants considering the severe dent caused by the 2008 and 2009 global financial crisis. However, Wilhelmsson (2000) counters this argument with a claim that even after the significant improvements witnessed in the labour market, the nature of overrepresentation experienced in Sweden has led to intense undermining tendencies on immigrants even though on the surface, the numbers of immigrants being integrated into the economic system is improving. As interviewees indicated, an immigrant’s ability to obtain a job does not mean that it offers a salary or contract commensurate with their skills and experience. In fact, the opposite is more often true. Additionally, R.Y. noted, “The difficulty for us as migrants with highly educated [sic], may be our specialization is not desirable or there is difficulty in finding work within our field. This compels us to try to find alternative methods such as studying another specialization and we do not know whether it will succeed or not ” (Appendix A). The difficulty for immigrants to truly become integrated into the economic system guides this research’s focus and demonstrates the muted tendencies of discrimination against educated and/or skilled immigrant workers in Sweden. For that reason, a thorough review of current evidence and proper theoretical foundation will guide the assessment of evidence from respondents who have participated in the Swedish labour market as educated and/or skilled immigrants.

Skill-based Employment Discrimination Against Immigrants

Dhanani et al. (2018) defined workplace discrimination as the act of causing unfair discrimination against people by group, class, or by other group characteristics as they see fit. Dietz et al. (2015) identified that discrimination against educated or skilled immigrants in Sweden is grounded in wage gaps, poor working conditions, and lower employment security rates. From this perspective, it seems that partial treatment of native and non-native workers in the labour market shows that the academic and professional credentials and capabilities of skilled immigrants are significantly devalued despite the low but steady rise in unemployment rates of this population. Sakamoto et al. (2013) support the argument that there is a high probability that a skilled immigrant may experience exclusion from employment opportunities afforded to native individuals with similar characteristics seeking the same job opportunities. This literature is relevant to my research because it demonstrates that it is possible for highly educated immigrants to have difficulty securing a steady job despite their educational qualifications and technical skills even when it is possible to secure an initial job opportunity. Of those surveyed, 59% agreed, “I feel that my ethnicity plays a bigger role in determining my salary in Sweden than my level of education or experience” (Appendix B). Skedinger (2018) attempted to analyze non-standard employment in Sweden and stated that in Sweden, both immigrants and natives are to an extent at a disadvantage of not receiving adequate pay because of improper contracts. Skedinger’s study can assist in explaining why those of Swedish origin tend to be treated fairly while those with a foreign background are discriminated against in securing a job.

Research by Arai et al. (2011) has also revealed that the traditional culture of naturalization and normalizing white privilege, which refers to the identity and assimilation of non-immigrants into their social systems, was the root cause of the continuing anxiety of post-industrialization discrimination. It entails new forms of discrimination that emerged after integrating labour forces after the labour market’s mass revolution. Forty-six percent of respondents indicated that “Swedish colleagues, employers, or managers have asked me questions about my culture, race, or lifestyle that have made me uncomfortable” (Appendix B). Wilhelmsson conducted a similar type of study in 2000, in which prejudgment and inequity were established within institutional settings and fashioned by the key market players based on their experiences and perceptions of a perfect Swedish labour market. It is a daunting task for organizations or employers to institutionalize traditions that appreciate diversity and subsume systems that discriminate against educated immigrants’ endeavours in the labour market. To do so risks flouting the flagrant examples of system justification theory within the structures underpinning the Swedish labour market, which would in turn defy a carefully curated panacea for a rise in apparent nationalistic anxieties following the global financial crisis. As Behtoui (2007) identified, market establishments are developed and nurtured by Swedish natives.

This literature acknowledges that educated immigrants face discrimination because of the majority population, implying that the Swedish natives or non-immigrants craft racial discourses intentionally or unintentionally against immigrants. It may limit access to resources and impose a set of unfair restrictions for compromising the immigrant’s access to social capital (Behtoui, 2007). Indeed, O.L. indicates “Although I have a good relationship with [my colleagues], but I do not feel that I am one of them, sometimes they meet after work, but no one has invited me with them, I do not know what the reason is, even though I tried to invite some of them to lunch several times, but I feel that I am ignored by them” (Appendix A).

Skill-Discounting and Devaluation-Based Skill Paradox

Researchers such as Sakamoto et al. (2013) have also examined the extent to which discriminatory discourses are portrayed among immigrants through skill devaluation. Their research begins by highlighting the basic understanding of skill discounting among various scholars and labour market experts. It identified that this happens when the academic credentials, technical skills, and professional expertise of immigrants are poorly recognized in the labour market. This means that immigrants with such achievements or significant attributes are evaluated worse in various job settings than native Swedes. Of greatest interest is that this issue occurs both at the institutional and individual levels, where immigrants encounter severe biases in different job contexts. For instance, a study by Dietz et al. (2015) reveals that educated Chinese workers in Sweden can be denied equitable wages, and 69.2% of respondents indicated, “I feel like I constantly have to prove myself and my worth because I am consistently underestimated by my Swedish colleagues, employers, or managers based on my race” (Appendix B).

The OECD Employment Outlook report shows that the set of hypotheses introduced into the econometric analysis of the panel that interests us here has been easier to explain and understand but more restrictive than that introduced in the 2003 document (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2019). The OECD report includes a linear equation that characterizes the determination of the unemployment rate of a country in the year, with a set of terms each relating to an explanatory variable observed in each country and each year multiplied by a coefficient that applies uniformly to all countries and years.

Additionally, in countries with extended support programs for the unemployed, as is the case in OECD countries, their high costs coupled with assessments of the motivation of beneficiaries have promoted the development of active policies. It is expected that a good design not only helps bring them down but also to increase numbers of effective job offers. This is the case of programs aimed at groups with specific problems. Equity considerations are involved, seeking to cushion the negative effects on some structural reforms or technological change on workers, etc. These programs may be motivated by the desire to redirect the labour market results, even when these are not due to failures in this market. Again, this type of motivation also presents the objective of increasing the effective offer of work and their qualifications.

In general terms, in OECD countries, the programs with the best results are search and placement assistance, although the rest of the programs are successful for specific groups. In terms of population groups, women benefit from a wide range of interventions. At the same time, young people constitute the group most difficult to help, at least when evaluating the effect on labour market variables. These overall results are undoubtedly affected by the macroeconomic and institutional contexts, and in fact, there are disparities in the results between countries. For example, among those immigrants surveyed in Sweden, 56.4% indicated, “I found my job through a certain program (such as Job Centre) and was given a low salary with a temporary contract because I used that program” (Appendix B).

The report by OECD also includes goals and intervention strategies in other contexts that are motivated by different reasons: probably the most-cited ones refer to the need to correct some market failure, such as information problems, insufficient qualification of the workforce, or difficulties accessing credit. That supports labour intermediation, training programs, and support for small businesses, respectively.

Many organizations have failed at meeting the OECD goals adopted by the country because the issue negatively affects the welfare of workers. Through designing a field experiment, a study by Jost (2017) has managed to determine that even though all participants of Swedish and Chinese backgrounds had equal qualifications for employment opportunities, job applicants with foreign identities or even backgrounds were less likely to qualify for an interview or job appraisal than the applicants with native Swedish backgrounds. Research by Wilhelmsson (2000) supports this perspective. It reveals that these issues can be very costly as immigrants advance further in skills and education. For instance, more time must be allowed in school to accommodate immigrants who learn more slowly, and the government must pay for the expenses. Other issues can be the provision of accommodation and health facilities. Current research illustrates immigrants wishing to secure a higher academic level in a given field of expertise such as healthcare, even if there would be few chances to secure advanced positions in the healthcare sector and in the job itself. It will help determine if the employment and skill appreciation rates decrease with the increase in skill levels among immigrants compared to natives.

Further, a study by Goudarzi et al. (2020) identified that the devaluation of educated and skilled immigrants in Sweden also emanates from organized institutions or entities. Organisations that use the agencies to hire workers tend to show some harboured latent biases that devalue immigrants’ skills seeking a solution to a job-related issue. All this indicates that, indeed, there has been a dearth in the voices meant to unmute the discriminatory discourse against immigrants in the country for decades. As immigrants possess more advanced skills and education in a given profession, it becomes difficult for them to be recognized by native institutions or even stand a chance to increase job security opportunities. Data from several interviews indicates that increase in educational attainment among immigrants seldom increases their chances at securing a job offer commensurate with their education and experience. Indeed, 61.5% of respondents had a Bachelor’s degree, and 30.8% had a Master’s degree or PhD. Of those respondents, 71.8% received their degree from their homeland and 20.5% received their degree in Sweden (Appendix B).

Table of contents :

Abstract

Introduction

1.1 Problem Statement

1.2 Limitations of the Study

1.3 Background

1.4 Thesis Structure

Literature Review

2.1 Skill-Based Employment Discrimination Against Immigrants

2.1.1 Skill-Discounting and Devaluation-Based Skill Paradox

2.1.2 Threat-Based Skill Paradox

2.2 The Influence To Attaining Total Integration Policy For Immigrants In Sweden’s Labour Market

2.3 Policies For Integrating Immigrants Into Sweden’s Labour Market

Theoretical Framework

3.1 System Justification Theory

3.2 Capitalism in Sweden

3.3 Social Identity and Discrimination

Chapter 4 Methodology

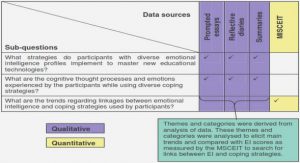

4.1 Researching Discrimination Among Immigrant Workers

4.2 Informants

4.2.1 Inclusion Criteria

4.2.2 Exclusion Criteria

4.3 Study Design

4.4 Data Collection

4.5 Interpretation of Data Collected

4.6 Ethical Considerations

4.7 Overview

Chapter 5 Analysis

5.1 Discrimination of Educated and/or Skilled Immigrants

5.2 A Steady Job for The First Time

5.3 Exploitation and Job-Related Difficulties

5.4 Actions and Responsiveness By Relevant Authorities Against Discriminatory Acts

5.5 Job Difficulties and Obstacles

5.6 Education Efforts for Enhancing Immigrants’ Skillset

5.7 Policies for New Immigrants in the Labor Market

5.8 Organizing Integration Efforts

5.9 Social Security Policies and Economic Integration

5.10 Conflicts Of Interest and Immigrant Women

5.11 Wage Policies and the Integration of Immigrants

Chapter 6 Discussion and Conclusion

6.1 Discussion

6.2 Conclusion

References

Appendix A: Interviews

Appendix B: Survey Responses