Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Standard-Compliant Production

In 2012, 40% of the world’s coffee production was compliant with the standards of at least one certification. However, only 12% of the global supply was sold with certification, indicating an oversupply of certified coffee (Potts et al., 2014). The top five producers of standard-compliant coffee are Brazil (40%), Colombia (17%), Vietnam (15%), Peru (6%) and Honduras (3%). Costa Rica produces 1% of the world’s standard-compliant coffee (Potts et al., 2014). Sales of nearly all standard-compliant coffee have experienced double-digit growth rates between 2008 and 2012. The rate of growth in 4C (Common Code for the Coffee Community)3 was 90% between 2008 and 2012 for a total in 2012 of 152,708 metric tons. This was followed by Rainforest Alliance with a growth rate of 28% between 2008 and 2011 and 2011 total sales of 129, 846 metric tons. Utz experienced a 25% increase in global sales between 2008 and 2012 with a 2012 total of 188,096 metric tons. CAFE Practices grew by 14% in the same time period with 223,230 metric tons of sales in 2012. Fair Trade’s 2008-2012 growth rate was 13% with a 2012 total of 128,000 metric tons. Sales of organic certified coffee grew by only 4% between 2008 and 2011 with a 2011 total of 133,163 metric tons (Potts et al., 2014). Despite the growing importance of other certifications, current research focuses mainly on Fair Trade and organic certification.

The Coffee Industry in Costa Rica

In Costa Rica, coffee production is the principal source of income for 50,000 farmers. Ninety-two percent of these farmers have fewer than five hectares of land. These small and medium-holder farmers account for 40% of Costa Rica’s annual harvest (Icafe, 2013b). Coffee production in Costa Rica is highly technified and input-intensive (Rice, 2015).

Classifications of Coffee Quality in Costa Rica

The quality and price of coffee is largely dependent on the elevation at which it was produced (Bosselmann et al., 2009). Coffee quality in Costa Rica is classified as Strictly Hard Bean (SHB), Good Hard Bean (GHB), Hard Bean (HB), Medium Hard Bean (MHB), Medium Grown Atlantic (MGA), Low Grown Atlantic (LGA) and Pacific (P) (Castro, 2013); the first four of which are the most commonly produced in the cooperatives studied. See Table 3 for a summary of the coffee qualities found in regions with cooperatives.

SHB is mainly grown between 1200 and 1700 meters above sea level (masl) in the Central Valley and Tarrazú, with some production in Coto Brus. SHB is valued for the hardness of the bean and its high acidity, body and aroma. GHB is produced between 1000 and 1200 masl, mainly in the West Valley. It is also known for the hardness of the bean and high acidity. Some lots have excellent aroma. HB is produced between 800 and 1200 masl in Guanacaste and parts of the West Valley. It has good body and aroma, but lower acidity than the previous varieties. MHB is produced at 400-1200 masl in Coto Brus and has medium hardness, body and aroma (Castro, 2013).

Farmers’ organizations in Costa Rica’s coffee industry

Collective action has a long history in the coffee industry in Costa Rica. The first recorded meeting of coffee producers organizing to defend their interests is in 1903 in the region of Tres Ríos. In the following forty years producers in other regions of the country met to ‘free themselves from the tyranny of the mills’ (Castro, 2013). Farmers’ organizations in Costa Rica are classified into associations, cooperatives and consortia, each of which are governed by different legislation (Faure, Le Coq, & Rodriguez, 2011). The Ley de Asociaciones 218 governs associations and the Ley del Cooperativismo 4179 governs cooperatives (Gobierno de Costa Rica, 1968). Costa Rica’s first cooperative mill was CoopeVictoria in Grecia, West Valley. CoopeVictoria was formed in 1943 when the Costa Rican government seized the private mill of the German Niehaus family and allowed the producers in the area to form a cooperative (Castro, 2013). The 1960s saw an increase in the development of the coffee cooperative sector. Cooperatives opened nearly every year between 1958 and 1972 in all coffee-growing regions of the country (Castro, 2013). The 1960s also saw the creation of the Federation of Cooperatives of Coffee Growers (FEDECOOP) which was created to increase cooperatives’ agency in exportation (N. L. Babin, 2012). Cooperatives purchase ripe coffee cherries from members and provide services such as milling, commercialization, credit, training, advisory services.

Today approximately 40% of exports are processed by cooperative-owned mills (Icafe, 2013b). The policies that support the cooperative sector have been credited with preserving small-holder agriculture and easing rural unrest (N. L. Babin, 2012). Cooperatives are an important vehicle for communicating new information to producers and providing access to services, such as marketing, credit and access to affordable inputs (Luetchford, 2008). Members of cooperatives are more likely to employ new agricultural practices than small non-affiliated producers and cooperatives are more likely than private mills to employ an agronomist to give agricultural advice to members (Castro, 2013).

Costa Rican Cooperatives and Regions

Costa Rica is divided into eight coffee-growing regions, six of which have active cooperatives. Cooperatives are found in the Central and West Valleys (Valle Central and Valle Occidental), Trés Rios, Tarrazú, Guanacaste and Coto Brus (Brunca). No cooperatives are located in Orosi or Turrialba (See Figure 2). Cooperatives are diverse and for example vary greatly in size from CoopeSantaElena in Monteverde with 25 members to CoopeTarrazu in Tarrazú with 2900 members.

Coto Brus (Brunca) Cooperatives

Coffee production moved into Coto Brus in the 1960s. The Coto Brus region produced 16% of the Costa Rican coffee harvest in 2013/2014 (Icafe, 2014). The coffee plantations in this region are more fragmented than in the historic centers of production like the Central Valley. This has resulted in smaller farm size and fewer large estates in this region (N. Babin, 2014).

There is a cluster of three cooperatives in Coto Brus near the Panamanian border: CoopeSan Vito, CoopeSabalito and CoopePueblos. CoopeAgri is located farther north in San Isidro de El General. CoopeAngeles is also located in this area but was not visited due to the remote location and the lack of viable contact information. It is not included in the data in this document. All are cooperatives of small-scale farmers located over 250 km from the capital.

Because of the diversity of the described above, cooperatives in the different regions choose to pursue different certifications based on the quality and amount of coffee produced, as well as on their individual marketing strategies. The factors which determine the extent of participation of different types of cooperatives are further discussed in Chapter 4. The choices that cooperatives make regarding the management of certifications and the market incentives which influence these choices have implications for the promotion of sustainable farming practices (Chapter 5) and on the equality and solidarity within the cooperative (Chapter 6). The frequency of certifications is summarized in Figure 3, which is based on the results of the census of cooperatives.

The Costa Rican Coffee Sector

Costa Rica has a long history of collective action in the coffee industry, starting in 1903 when farmers first organized themselves to defend their interests against large exporters (Castro, 2013). Many cooperatives entered into the certified coffee market with Fair Trade certification, which was first available in Costa Rica in 1988 (Luetchford, 2008). Costa Rica is an important producer of certified coffee and its production of standard-compliant coffee approaches 30% of the country’s total production (Potts et al., 2014).

Unlike many of its Latin American neighbors, coffee production in Costa Rica is dominated by small-holder farmers. Ninety-two percent of the nation’s coffee farmers have farms of less than 5 hectares. The harvest from farms of less than 5 hectares represents 40.5% of the nation’s total harvest (Icafe, 2014). Costa Rica is Central America’s fourth-largest coffee producer, after Honduras, Nicaragua and Guatemala (International Coffee Organization, 2015). The majority of coffee production in Costa Rica is under at least one species of shade tree (Instituto Nacional de Estadisticas y Censos, 2007) and is heavily-dependent on agrochemical inputs (Rice, 1999).

Table of contents :

Chapter 1: Introduction

Abstract

Résumé

Resumen

Voluntary Coffee Certifications and the Global Coffee Market

Certification Standards

Standard-Compliant Production

Farmers’ Organizations

Problem Statement

Chapter 2: Methods

Abstract

Résumé

Resumen

Study Design

Chapter 3: Costa Rica’s Coffee Cooperative Sector

Abstract

Résumé

Resumen

The Coffee Industry in Costa Rica

Classifications of Coffee Quality in Costa Rica

Farmers’ organizations in Costa Rica’s coffee industry

Costa Rican Cooperatives and Regions

Central Valley, West Valley and Trés Rios Cooperatives

Tarrazú Cooperatives

Guanacaste Cooperatives

Coto Brus (Brunca) Cooperatives

Chapter 4: Small Farmer Cooperatives and Voluntary Coffee Certifications: Rewarding Progressive Farmers or Engendering Widespread Sustainability in Costa Rica?

Abstract

Résumé

Resumen

Introduction

The Costa Rican Coffee Sector

Voluntary Coffee Certifications and Global Production

Materials and Methods

Results and Discussion

Implementation of Certifications by Costa Rican Coffee Cooperatives

Financial Incentives for Cooperatives

Paying Certification Premiums to Members

Conclusion

Chapter 5: Voluntary Coffee Certifications Influence how Cooperatives Provide Advisory Services to Smallholder Farmers in Costa Rica

Abstract

Résumé

Resumen

Introduction

Costa Rica and Voluntary Coffee Certifications

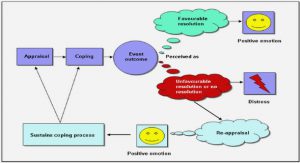

Conceptual Framework

Materials and Methods

Results and Discussion

Changes at the cooperative level

Changes in farming practices

Conclusions

Chapter 6: Social Capital and Sustainable Coffee Certifications in the National Context of Costa Rica

Abstract

Résumé

Resumen

Introduction

Classifying social capital to predict collective action

Voluntary Certifications in Costa Rica

Materials and Methods

Organizational social capital

Social capital of cooperative membership

Results and Discussion

Social Capital in Cooperatives and the Effects on the Management of Certifications

Generalized Trust and Voluntary Participation in Certification

Social Capital and Certifications: A Virtuous Cycle?

Considering the National Context When Implementing Certification Schemes

Conclusions

Chapter 7: Synthesis

Abstract

Résumé

Resumen

Introduction

The synergy between cooperatives and certifications

The structure of the coffee sector affects the efficacy and management of certifications

Environmental and social regulation and enforcement

Law 2762: regulating coffee quality and relations between producers and millers

Strong Cooperative Sector and Institutional Support

Social Capital in Costa Rica

Financial benefits of certification

Certification premiums are variable and poorly incentivize farmers

Non-financial benefits of certifications

Promoting a holistic approach to coffee production

Increased human and social capital

Balancing financial incentives with member equality

Balancing extrinsic and intrinsic motivations

Limits of the study

Recommendations

Chapter 8: Conclusions

Abstract

Résumé

Resumen

References