Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Gendered language

Gendered language is not very common in English, and it can be difficult to determine the gender of a person without any additional context being provided, such as their ap-pearance or the sound of their voice. This is in stark contrast to Japanese, in which the pitch, vocabulary, sentence-final particles, pronouns, and phrasings can all differ de-pending on the gender of the speaker (Okamoto, 2016).

Another component of gendered language in Japanese is the assertiveness or non-as-sertiveness of the speaker. A stereotypical male tends to be more assertive when they speak, and often use rougher language such as emphasized male pronouns and sen-tence-ending particles. In the case of a stereotypical female, softer language is used, and they tend to be indirect with their assertions as a result. This assertiveness can be accomplished by vague suggestions, which puts the onus on the listener to fill in the blanks. Both masculine and feminine language in Japanese have particular sentence-ending particles associated with them, such as wa (feminine language) and zo (mascu-line language). These sentence-ending particles can give the reader an idea of the gender of a certain character.

In English, differences in how characters of different genders interact with others and speak is usually implied through their gender, or explicitly shown to the reader. That is to say, such differences do not present themselves in the written dialogue, but instead form a surrounding context to the dialogue.

In Japanese, such differences can be present in spoken language, and as such they can also be observed in written dialogue. A Japanese translation of English dialogue can therefore end up being more gendered. Certain characteristics may be emphasized as a result. This can give the character added personality, and influence the impression the character gives the reader, without the content (i.e., the actual intended meaning) being altered. Gendered language and yakuwarigo can lead to more distinct characters in a work of fiction, which could explain why they are so prevalent, especially in fictional works aimed at younger audiences.

Additionally, whether a character’s mode of speaking is Onna-rashii (女らしい) or Otoko-rashii (男らしい) can be determined (Meryl, Okamoto, 2003: 49-66). These terms translate literally to women-like and man-like. Male speech in Japanese is thought to be more contracted, with more limited use of vowels; it can also be con-sidered “impolite” as a result. Characteristics of female speech in Japanese include a more prevalent usage of honorific language, and a higher register. This aspect of gendered language is more difficult to identify in written text.

Yakuwarigo

Yakuwarigo is a term coined by Satoshi Kinsui, in his book Vācharu nihongo yak-uwarigo no nazo (Virtual Japanese, the riddle of role language, published 2003), to de-scribe role-specific language in works of fiction. It is not usually the type of language that one would encounter in real-world settings. Yakuwarigo describes language that is strongly related to a certain character archetype, which can vary depending on gender, age, social status, and personality. For example, older characters in Japanese fiction of-ten speak in very similar ways, using specific pronouns such as washi, specific sen-tence-ending particles, and vocabulary that would not be very common in normal con-versation. The voice of an older character is very different from that of a boyish char-acter that might use a pronoun such as oira to refer to himself. Yakuwarigo serves to make characters more distinct from one another, and evokes a certain image of a char-acter archetype which the author wants to convey to the reader. At the same time, yak-uwarigo can serve to make characters more generic, since certain characters will be very similar to others that are of the same archetype.

According to novelist Shimizu Yoshinori, Japanese dialogue in fiction is written to ful-fill certain functions (Hasegawa, 2011:130). Therefore, according to Yoshinori, con-versations in fiction should not be written to be too real. This allows the reader to un-derstand the information being given, and the relation between characters, without too much detail bogging down the story. Due to yakuwarigo, and the aforementioned Ja-panese strategy for writing fiction, the speaker of a certain line can be inferred from context, and need not be explicitly indicated. Of course, not all Japanese authors or translators subscribe to the strategy mentioned.

Yakuwarigo is not as well-defined as gendered language, since there are a much larger number of roles that a certain character can have than there are genders. As a result, role language can be harder to categorise. Furthermore, new roles, and subsequently new yakuwarigo, can also be created by an author in order to convey a certain image to the reader. Examples of categories, according to Kinsui Satoshi, include: “Elderly Male Language”, “Rural Language”, and “Student Language.” These are all languages spoken by certain character archetypes, and differ from what Kinsui refers to as “Standard Language.”

Previous Studies

This study focuses on a manual translation of the book Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets conducted by Matsuoka Yuko. It has been difficult to find relevant previous studies on manual translations, especially higher-level papers written by experts on the subject.

Previous theses – for instance, Dorien Heerink’s “Yakuwarigo Lost in Translation: A Foreignising approach to Translating Yakuwarigo” published in 2018 – similar to the present study have examined the change in character portrayals when a text is trans-lated from Japanese to English. Theses observing the opposite phenomenon – that is to say, translations from English to Japanese – are harder to come by, even when looking at advanced-level studies. This thesis aims to fill this gap in the research.

This study focuses on the effect that gendered language and yakuwarigo has on char-acter voices. As such, previous studies on these topics may be of interest to the reader.

Previous studies on gendered language

A previous study that is of some interest for this project is Bridget Jones’s Femininity Constructed by Language written by Furukawa Hiroko and published in 2009, which evaluates differences between the English version of the book and the Japanese subti-tles of the film Bridget Jones’s Diary. In the study, the author argues that Japanese women in real-life settings do not use the same kind of language that women in fiction do. This discrepancy is particularly prevalent in translations from foreign languages into Japanese, and is regarded as a conventional Japanese translation method (Inoue, 2003). The use of feminine language in Japanese that can be seen today stems primar-ily from the Meiji period (1868-1912). It was during this period that conventions in feminine language, such as specific sentence-ending particles, became prevalent (Kindaichi. 1988: 39). These conventions became reinforced during the gender-segre-gated schooling that followed during the Meiji period. In modern society, especially among younger generations of Japanese women, such language is no longer as com-mon. Yet gendered language still remains in Japanese fiction, and especially in transla-tions from foreign languages such as English.

According to the aforementioned study by Furukawa, there is an exaggeration of the female character Bridget Jones in the Japanese translation of the book Bridget Jones’s Diary. This presents itself as an overuse of feminine language, in contrast to the man-ner in which Japanese women speak in real-world settings. Exaggeration of dialogue is a common strategy employed in Japanese literature, in order to emphasize certain characteristics (Inoue. 2003: 2). If a certain character is considered particularly femi-nine, this can be expressed through dialogue by use of exaggerated feminine language. For instance, sentence-ending particles such as wa can be used, or more polite lan-guage can be used in order to imply a more submissive or soft nature.

The difference between the aforementioned study and this one, is that the material be-ing observed in this study is aimed at teenagers and other children, and has a fantasti-cal theme. This is in contrast to Bridget Jones’s Diary, which is a book with a feminine theme, written primarily for young adult women. The emphasis on gendered language could therefore, in part, be due to the gender-related theme of the book that was stud-ied.

Previous studies on yakuwarigo

Role language is a concept first established by Kinsui Satoshi in 2003. It is a way of speaking that encompasses vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation. These are adap-ted to the speaker’s social and cultural stereotypes. Characters can use certain first-per-son pronouns, copula, and sentence-ending particles. The use of role language can pose a difficulty in translating fiction to and from Japanese.

Role language, or yakuwarigo, can aid an author in creating more distinct character voices, since each character will speak in a particular manner depending upon their role in the story. Furthermore, role language can have the effect of adding pragmatic and phonetic characteristics to a character’s voice (Kinsui, 2003: 131).

In Japanese dialogue, personal pronouns are often omitted, since they are not used for the purposes of text cohesion as they are in English (Hasegawa, 2011: 144). When reading dialogue, it can therefore be difficult to determine who is speaking. By using role language, each character voice becomes so distinct that it is easy to identify which character is currently speaking based purely on their manner of speech.

Each character plays a certain role in the story, and in Japanese fiction characters speak in a distinctive way that tells the reader what their role is. A fitting example is the character Dumbledore from the Harry Potter-series. Dumbledore fits into the char-acter of a “Mentor”, and therefore must speak in an elderly male language-type in Ja-panese. This change can be seen in the translations of the books by Matsuoka Yuko (Kinsui. 2003: 30). According to Kinsui, if characters are not assigned roles in this way, they become background figures who quickly fade from the readers’ memories. This would be contrary to what Japanese readers have come to expect. These changes can have the effect of altering the character voices during the translation process.

Method and Material

The effect of gendered language and yakuwarigo on the Japanese translation of Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

The aim of this study was to evaluate if and how gendered language and yakuwarigo affect the character voices of the characters Hermione, Hagrid, Dumbledore and McGonagall, when translated into Japanese. The evaluation was accomplished through means of an analysis of the respective characters’ lines of dialogue, as well as through the use of questionnaires concerning the role and gender of the characters.

Material

The focus of this study was the book Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets by J.K. Rowling. The original had a length of 341 pages, however only certain lines from specific characters were used. The book was originally published in 1998 by the UK pub-lisher Bloomsbury. It was published a year later by the publisher Raincoast in the US.

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets is centred around the protagonist Harry Pot-ter, and his close friends in Hermione Granger and Ron Weasley. The Chamber of Secrets refers to a hidden room in the school of Hogwarts, a school of wizardry and magic. A great creature is hiding somewhere in the school, leaving only to attack their fellow students. Together, they try to uncover what is happening, and save Hogwarts.

The translation used in this study was written by the author Matsuoka Yuko, and was published January 1st of the year 2000. The publisher was Say-zan-sha Publications Ltd.

The characters that were analyzed are: Hermione (a schoolgirl), Hagrid (the grounds-keeper at Hogwarts), McGonagall (an older teacher at Hogwarts), and Dumbledore (the principal of Hogwarts).

These characters were chosen because they belong to very distinct archetypes and to different age-groups. It follows then that they could be more affected than other char-acters in the book when translated into Japanese, due in part to yakuwarigo, but also gendered language.

Methodology

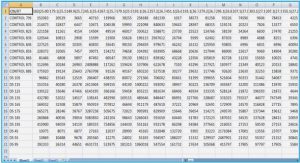

A selection of dialogue from the characters Hermione, Hagrid, Dumbledore and McGonagall was extracted from the English version of the book. The first 11 lines for each character (each line was not allowed to be fewer than 10 words or more than 35) were extracted from the source text (ST) and the corresponding parts in Japanese were identified in the target text (TT). These were then compiled into a spreadsheet, and presented side-by-side, in order to simplify the analysis.

Excerpts of dialogue were also used in creating two questionnaires: one for native speakers of Japanese (who analyzed the Japanese version of the text), and one for nat-ive speakers of English (who analyzed the original version of the text). The aim of the questionnaires was to observe how clear it is from nothing but the lines of dialogue which gender the speaker of a certain line is, as well as if the character fits a certain ar-chetype.

The questionnaires were designed not to be too long, in order to attract more parti-cipants. There were ten questions in total: 4 pertaining to gendered language, 4 per-taining to role language, and 2 optional open questions that required participants to translate lines to Japanese or English (whichever their non-native language may have been). A selection of lines that exhibited influences of yakuwarigo and gendered lan-guage were used in the questionnaire. The exact same lines were used in both versions of the questionnaire, which made it easier to draw direct comparisons later in the study.

The participants were found through social media, specifically through the sites Reddit and HelloTalk. Reddit is a primarily English-speaking network of forums. HelloTalk is a language-learning platform with many Japanese native speakers. Posts were made on these two platforms targeting the two distinct groups of participants.

The names of the characters were not presented to participants of the questionnaires. The participants were asked to determine which lines belong to what type of character role, as well as what gender the character is. At the end of each questionnaire, the par-ticipants were asked to translate specific lines in the books from their secondary lan-guage to their native language.

When the data-gathering was concluded, an analysis of the extracted lines com-menced. The analysis focused on yakuwarigo and gendered language.

A line was considered to include gendered language if it included: gender-specific sen-tence-ending particles (such as wa or zo), gender-specific pronouns, or vocabulary more typical for a certain gender. How the aforementioned concepts influence the voice of characters were evaluated, in order to answer the main research question of the study.

Identifying characteristics of gendered language

The primary characteristics of gendered language are well-established. The below tables are based on studies surrounding gendered language conducted by Okamoto Shigeko and Smith Shibamoto (Okamoto, Shibamoto, 2004: 120-121). These will be used in evaluating whether a certain line is gendered or not.

Table of contents :

1 INTRODUCTION

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 GENDERED LANGUAGE

2.2 YAKUWARIGO

3 PREVIOUS STUDIES

3.1 PREVIOUS STUDIES ON GENDERED LANGUAGE

3.2 PREVIOUS STUDIES ON YAKUWARIGO

4 METHOD AND MATERIAL

4.1 THE EFFECT OF GENDERED LANGUAGE AND YAKUWARIGO ON THE JAPANESE TRANSLATION OF HARRY POTTER AND THE CHAMBER OF SECRETS

4.2 MATERIAL

4.3 METHODOLOGY

4.3.1 Identifying characteristics of gendered language

4.3.2 Identifying characteristics of role language

5 RESULTS

5.1 COLLECTED LINES

5.2 QUESTIONNAIRE RESULTS

6 ANALYSIS

6.1 HERMIONE

6.2 HAGRID

6.3 MCGONAGALL

6.4 DUMBLEDORE

6.5 QUESTIONNAIRE RESULTS

6.5.1 English questionnaire

6.5.2 Japanese questionnaire

7 DISCUSSION

7.1 IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY

7.2 LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

8 CONCLUSIONS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

APPENDICES

Appendix I: Hermione’s Lines

Appendix I: Hagrid’s Lines

Appendix I: McGonagall’s Lines

Appendix I: Dumbledore’s Lines

Appendix II: English Questionnaire

Appendix III: Japanese Questionnaire