Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC AND SPATIO-TEMPORAL VARIATION IN HOMICIDE RISK: THE EVIDENCE

This review suffers from the fact that there is a dearth of published analytic studies on homicidal strangulation risk specifically. For this reason, the section will focus on evidence as related to homicide in the aggregate and, where available, on firearm homicide which has received the most attention in research on disaggregated homicide. In particular, the review will consider findings on age-, race- and sex-specific predictors of homicide, and the temporal and micro-spatial factors that are predictive of risk.

Research indicates that one of the most stable explanations for the disproportionate distributions of fatal violence risk across time and place is demographic variation, as applicable to age, race and gender (e.g., Cohen & Land, 1987; Fox & Piquero, 2003; Trussler, 2012). Demographic factors have thus become central to predictions of homicide. While demographics are not the only, or conceivably the strongest, predictor of homicide rates, and very likely interact with other risk factors, they are widely accepted as a strong predictor of homicide rates. Spatio-temporal factors call into focus the relationships between homicide and characteristics of the physical and social environments in which homicide concentrations occur (Groff & La Vigne, 2002), as well as temporal variations associated with lethal violence, which are commonly associated with changes in human activity patterns (e.g., Ceccato, 2005).

Socio-demographic Risks

According to Trussler (2012), the age-homicide link holds across studies, demonstrating a robust association. This relationship is largely supported by research undertaken in the North, such as in the United States, United Kingdom and Canada, where the young, and male, population has been found to be at highest risk for lethal violence (e.g., Schwartz, 2010; Trussler, 2012; also see Schneider, 2015). Specifically, vulnerability is reported to be elevated in the 15-29 year age group, followed by the 30-44 age category, and to decline steeply with age thereafter; again, this is for males and considerably pronounced relative to the estimated risk for females in the same age groups (e.g., Krug, Dahlberg, Mercy, Zwi, & Lozano, 2002; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2011). When disaggregated, the established predictive patterns are strongly analogous to those determined for firearm homicide (e.g., Krug et al., 2002; Miller, Hemenway, & Azrael, 2006;Wells & Chermak, 2011). A comparable pattern is evident in South Africa (see Kramer & Ratele, 2012; Seedat, Van Niekerk, Jewkes, Suffla, & Ratele, 2009; Thaler, 2011). At nine times the global rate (184 per 100 000), the highest homicide rates have been reported among males aged 15-29 years, (Norman, Matzopoulos, Groenewald, & Bradshaw, 2007; also see Norman, Schneider, Bradshaw, Jewkes, Abrahams, Matzopoulos, & Vos, 2010). The vulnerability of younger men to homicide has been ascribed to their more likely participation in violence related activities, such as criminal offenses in public places, gang membership, substance abuse and possession of weapons (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2011), typically influenced by dominant ideas of what it connotes to be a man (Ratele, 2008).

The racial homicide gap in risk is reportedly enduring and pervasive. There is consistent evidence in the international and national literature that black adults are at increased risk of homicide victimisation compared to other race groups, and that this risk is higher in urban settings and among young men than in other contexts or among other age-gender groups (e.g., Cubbin, LeClere, & Smith, 2000; DeJong et al., 2011; Kramer & Ratele, 2012; O’Flaherty & Sethi, 2010; Ratele, 2009; Schwartz, 2010). In North America, for example, African-American males are estimated to be approximately six times more at risk of being murdered than white American males (O’Flaherty & Sethi, 2010). Based on the finding that black females were more likely to be murdered than white males, O’Flaherty and Sethi (2010) observed that race is a more powerful risk factor than gender. This black-white homicide risk disparity has also been reported in South Africa (e.g., Kramer & Ratele, 2012; also see Shaw & Gastrow, 2001). Black South African males between the ages 20 and 40 are reported to be seventeen times more likely to be murdered compared to white males in the same age group (Ratele et al., 2011). Ratele (2010) explains that in extremely unequal societies, such as South Africa, human development opportunities for the population are vastly asymmetrical so that in the absence of employment and other optimal possibilities for young black males, violence comes to represent an alternative mechanism in some men’s attempts to assert their masculinity. An alternative explanation, and perhaps complementary to Ratele’s accent on masculinity, is offered by O’Flaherty and Sethi (2010), who maintain that the concentration of homicide risk among blacks cannot be sufficiently accounted for by individual characteristics. They argue that conceptualisations of risk must consider the notion of preemptive motive; that is, individuals sometimes kill purely to avoid being murdered themselves. They elaborate that in environments perceived to be dangerous, disputes within particular dyadic interactions have the potential to escalate, resulting in violence, as well as notable racial disparities in rates and risk of homicide victimisation. While explanations for the racialised risk profile described here may differ, the empirical evidence appears to remain firm.

As the age-sex and race-sex interactions indicate, gender is an important risk factor in homicide victimisation. Males are at a substantially higher risk of being murdered compared to females, at a global rate of 11.9 per 100 000 compared to 2.6 per 100 000 for females (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2011). Males are also far more likely to be murdered by strangers or acquaintances whereas women bear the greater risk of intimate partner homicide (e.g., Cao et al., 2008; Gallup-Black, 2005). In fact, across country contexts, the female homicide rate appears to be driven by intimate partner homicide. As with overall female homicide, intimate femicide is commonly referenced as an extreme manifestation of gender inequality, discrimination, power disparities and structural inequalities between the sexes, and the subordinated status of women in society (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2011). At a rate of 5.6 per 100 000, intimate femicide represents the leading cause of female homicide in South Africa (Abrahams et al., 2012). As already noted, homicide is the leading cause of injury in males (Norman et al., 2007). The marked sex structure and risk differentials for female and male victims of homicide victims appears to have remained relatively stable over time.

Situational Risks

While the combination of, and intersection between age, race and gender demonstrably account for variances in homicide victimisation risk, situational homicide patterns are also considered as essential to deciphering homicide risk (Pizarro, 2008). From a micro-spatial perspective, the crime location is considered to be an important variable both in overall homicide, as well as disaggregated homicide (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2011). Homicide events have been found to occur more often in some geographic locations than in others (Pizarro, 2008). In this respect, lethal violence is indicated to occur more often in public places through which people navigate in the course of their daily routines (e.g., Pizarro, 2008; Tardiff, Marzuk, & Leon, 1995). In general, this same pattern is iterated for males, but is the converse for females who are reportedly more likely to be murdered in private places (e.g., Swart, 2014; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2011). There is thus a discernibly gendered orientation to the relationship between sex and scene of homicide. Research also suggests that homicide in private spaces is more likely to involve a known perpetrator, unlike the pattern observed in fatalities in public spaces such as the street (e.g., United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2011). In fact, in their study, Cao and his colleagues (2008) found that public locations reduced the probability of murder by a known person, but increased the risk of being murdered by a stranger. Thus, evidence suggests that place matters in homicide, both with respect to the type of fatality, as well as the victim-offender relationship.

INTRODUCTION

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL PROFILES AND PATTERNS OF HOMICIDE

HOMICIDAL STRANGULATION

RATIONALE AND JUSTIFICATION

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

RESEARCH AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

METHOD

Research Context

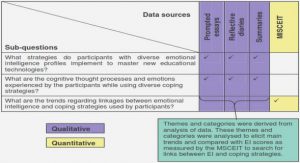

Data Sources

NIMSS

South African National Census

Data Analysis

Ethics Approval

STRUCTURE AND ORGANISATION OF THE THESIS

REFERENCES

STUDY I THE EPIDEMIOLOGY OF HOMICIDAL STRANGULATION IN THE CITY OF JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA

METHOD

Data Source

Data Analysis .

RESULTS

Incidence of Homicide and Strangulation .

Cause-specific mortality rates

Age-specific and race-specific mortality rates for homicidal strangulation

Circumstances of Strangulation Occurrence

Homicidal strangulation by time

Homicidal strangulation by place

Blood alcohol concentration levels

DISCUSSION .

CONCLUSION

REFERENCES

STUDY II SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC AND SPATIO-TEMPORAL PREDICTORS OF HOMICIDAL STRANGULATION IN THE CITY OF JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA

SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC AND SPATIO-TEMPORAL VARIATION IN HOMICIDE RISK: THE EVIDENCE

Socio-demographic Risks

Situational Risks

ROUTINE ACTIVITIES THEORY: EXPLAINING SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC AND SPATIO-TEMPORAL PREDICTORS .

METHOD .

Data

RESULTS

Strangulation Homicide Versus All Other Homicides

Model 1: Analysis of socio-demographic variables

Model 2: Analysis of spatio-temporal variables.

Strangulation Homicide Versus Firearm, Sharp Object and Blunt Object Homicide

Model 1: Analysis of socio-demographic variables

Model 2: Analysis of spatio-temporal variables

DISCUSSION

CONCLUSION

STUDY III RISK FACTORS FOR FEMALE AND MALE HOMICIDAL STRANGULATION IN THE CITY OF JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA .

DIFFERENITAL INDIVIDUAL-LEVEL HOMICIDE RISK BY GENDER .

FEMININITIES AND MASCULINITIES: THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES ON GENDER AND HOMICIDE

METHOD

Data

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

REFERENCES

STUDY IV NEIGHBOURHOOD CORRELATES OF HOMICIDAL STRANGULATION IN THE CITY OF JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA

SOCIAL STRUCTURE AND HOMICIDE: THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES AND EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

METHOD

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

CONCLUSION

REFERENCES

CONCLUSION

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT

HOMICIDAL STRANGULATION IN AN URBAN SOUTH AFRICAN CONTEXT