Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Documented changes in food chain governance in Asia and Africa

The quiet revolution in Asia

The ‘supermarket revolution’ brought to the fore a change in the organisation of food chains as the result of increased power from the downstream segment (Reardon et al., 2003). On the contrary, the quiet revolution (Reardon et al., 2012) shows a change in organisation driven by the midstream segment.

The authors documenting the quiet revolution selected three countries to represent the Asian continent: India, Bangladesh and the People’s Republic of China. The issues addressed are the transformation of the organisation of the rice and potato chains, the changes in conduct of actors and the inclusion of small-scale stakeholders. The benchmark situation of the quiet revolution is a traditional VC comprised of many intermediaries, using weakly capitalised technologies and yielding expensive, low-quality products. Producers buy few inputs, are poorly integrated into markets and are engaged in ‘exploitative relationships of tied credit-output linkages where traders lend to farmers and thus underpay and exploit them’ (Reardon et al., 2012, based on Lele, 1971).

Public policies were important in enabling the transformations (Reardon et al., 2012). There were investments in infrastructure such as irrigation canals, roads, power grids and mobile phone communication networks. Research and extension policies were also favourable to the modernisation. Few policies subsidized investments in processing techniques and improved inputs, although they were not common. Furthermore, financial capital from the agricultural and industrial sectors was available for investment, and the increase in average household incomes drove the demand for products of higher quality. Finally, the green revolution had enabled producers to intensify their practices and to increase yields and the share of produce sold (Reardon et al., 2012).

The modernisation is characterized by investments in new techniques and integration of the collection function. First, there was an expansion of the volumes of activity, followed by investments in new techniques in the midstream segment and the concentration thereof (Reardon et al., 2012). This change in techniques increased the capacity of husking (up to three tons per hour) and storage (from 180 to 3,000 tons from the 1990s to 2010) (Reardon and Minten, 2011). The number of large rice millers increased, that of small rice millers decreased (Reardon et al., 2014). Second, the tied credit-output market relationships with traditional collectors disappeared to give way to vertical coordination.

Midstream stakeholders integrated collection and sometimes set up contractual transactions with wholesalers (Reardon et al., 2012). Downstream, the changes tend to move toward the supermarket revolution. Mills add value to quality rice varieties through packaging, branding and traceability (Minten et al., 2010). The quality of rice is defined by the size and shape of the grain, and other attributes such as the degree of whiteness, aroma, cleanliness (degree of foreign matter), amount of broken rice and age of the grains.

The final retail price increases with the quality of rice, for instance by 69.2% with the production of fine rice in Bengladesh (Minten, Murshid, et al., 2013). The share in the final amount of the profit margin generated by all stakeholders along the chain also increased, while costs decreased. The change to quality rice is advantageous for millers and retailers, who for instance get respectively 44% and 49% of the quality premium for fine rice in Bangladesh (Minten, Murshid, et al., 2013). Producers may get a slightly higher income in absolute terms. For instance, ‘rice farmers in Noagoan received $198/ton for common and $218/ton for fine rice’ (Reardon et al., 2012: 144). Nevertheless, Minten et al. (2013) conclude that producers do not benefit directly from higher retail prices.

Modernisation is most advanced in the People’s Republic of China, where the modern VC dominates. In India, the modern VC is quickly expanding, although there are still collectors. Modernisation is less advanced in Bangladesh, where the traditional VC dominates, although transformation is emerging (Reardon et al., 2012).

Limited evidence for Africa

We selected an African country because there are policies on that continent which aim at modernising domestic food chains since the world food price crisis (Fofana et al., 2014) and specific VCs seem to be modernising (Reardon et al., 2013).

The supermarket revolution is not ongoing in many countries in Africa (Tschirley et al., 2010), with a few exceptions such as Kenya (Neven and Reardon, 2004). There has been a dominance of traditional food chains since the 1990s (Fafchamps, 2004). The environment is uncertain because of various constraints: low investment in road infrastructure, unstable production due to climate conditions and unstable demand due to low purchasing power (Fafchamps, 2004). Farmers and traders are limited in capital; they carry out transactions based on trust. Interactions are frequent and the choice of partners is made based on social linkage and reputation, which enables the sharing of risks among economic partners (Moustier, 2012).

But the recent evolutions in the institutional environment might be favourable to a revolution in domestic food chains. Price shocks on the global market affected the food security and income of the poorest households (Badolo and Traoré, 2015; Boccanfuso and Savard, 2011; Cudjoe et al., 2010). Several African governments set up policies aimed at modernising domestic VCs (MA, 2009; CARD, 2008).

Specific VCs in Africa seem to be modernising (Reardon et al., 2013). In Ethiopia, the increasing adoption of improved inputs and the rise in demand for high-quality produce were observed in the teff VC (Minten, Tamru, et al., 2013). In Tanzania, the food system supplies a wide variety of locally-processed, high-quality products which are competitive with imports (Ijumba et al., 2015).

We propose an in-depth analysis of the rice VC in Senegal where we will document modernisation characteristics that approximate those of the quiet revolution.

Conceptual framework

The quiet revolution framework is mostly empirical with some loose reference to the Structure-Conduct-Performance paradigm grounded on Bain (1959). This paradigm links the structure of markets (degree of concentration and differentiation of firms) to the performance of the sector (reduction of costs and generation of added value). It also analyses the distinct functions performed by the chain stakeholders, the techniques they use and their modernness in terms of scale and number of intermediaries.

We complete this paradigm with the GVC theory (Gereffi et al., 2005). This framework analyses important dimensions of the supermarket and quiet revolutions (Reardon et al., 2003, 2014), i.e. the influence that the institutional framework and the actor in a steering position have on the distribution of tasks and skills along the chain. It particularly focuses on links between changes in quality of product and the distribution of costs and benefits between VC members.

The GVC framework analyses the Global Commodity Chains, ‘a network of labour and production processes whose end result is a finished commodity’ (Hopkins and Wallerstein, 1986, p159). It takes into account the network theory, the literature on firm capabilities and learning and TCE (Bair, 2009). A Global Commodity Chain can be characterised by four dimensions: the input-output structure, the territory covered, the governance and the institutional framework.

The institutional dimension includes policies which can directly and indirectly influence the dynamic of governance. Direct interventions in the VC may be implemented by state agencies taking part in the transactions or defining new coordination mechanisms. Indirect interventions may constrain (norms and taxes) and support the actors of the VC (subsidies, technical support).

Governance is defined as the ‘authority and power relationships that determine how financial, material, and human resources are allocated and flow within a chain’ (Gereffi and Korzeniewicz, 1994, p97). Three variables, representing the characteristics of the industry and production process, explain the dynamics of VCs: the complexity of transactions, the ability to codify these transactions and the capabilities of the supply base. They determine five types of governance. Governance by the market concerns simple transactions in which price is the only element of co-ordination. When transactions are complex, but the suppliers can meet different forms of demand, this is referred to as modular governance. Relational governance describes transactions, often informal, in which the stakeholders are socially close, exchange information and may put in place personalised relationships, thus reducing uncertainty but also creating a situation of interdependence. Captive governance refers to the strong involvement of a leading firm in the operations of its suppliers. Finally, in hierarchy governance, the body of operations is controlled by the same stakeholder.

Technical change consists in the use of new production techniques, at the scale of millers or farmers. Producers may strengthen their skills with the implementation of new agricultural practices including improved varieties or chemical inputs. The quiet revolution is characterized by a technical change of the midstream segment. In Senegal, the traditional VC uses small-scale processing units that husk less than one ton of paddy per hour (Fall, 2006). Technical change is the process of moving to semi-industrial (husking between one and two ton per hour) or industrial (husking up to three tons per hour) techniques performing functions such as drying, cleaning and grading.

In the GVC framework, technical change tends to steer governance toward integration when it is combined with quality development, as it makes transactions more complex, hence requiring more control. Technical change may also lead to governance taking a more relaxed form, when it strengthens the skills of suppliers (Gereffi et al., 2005). Technical and institutional change erects barriers to entry, for instance through the improvement of quality, labelling, and strategies of integration (Kaplinsky, 2000). These barriers to entry determine the distribution of costs and margins among the stakeholders. Those setting up the innovation obtain the greatest share. Figure 1 shows the influences that technical change has on governance.

Therefore, the conceptual framework analyses the influences of the institutional environment and technical change on governance. It also analyses the changes implied in competitiveness of chains in terms of quality of product, quantity supplied, costs of production, stakeholder margins and final prices.

Methodology

We selected the rice VC in Senegal since it seemed to provide a good case reflecting the quiet revolution, with increasing investment in modern techniques and new co-ordination modes between producers and processors (Demont et al., 2013; Baris and Gergely, 2012; Demont and Rizzotto, 2012; Gergely and Baris, 2009; MA, 2009).

We conducted 154 in-depth interviews. We focused on stakeholders in the upstream VCs located in Dagana Department, since technical and co-ordination changes mainly occur at their level. We carried out 47 interviews with producers, 38 with small-scale and industrial rice millers. We also carried out interviews with 23 traders operating in Dagana and Dakar, including wholesalers and importers, and 46 interviews with agents of public and private research and development organisations. Topics discussed were policies, stakeholder behaviour, quality management and changes in co-ordination.

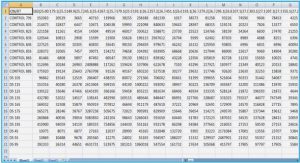

We also used quantitative questionnaires to assess the distribution of margins and costs along the chain in 2014. Databases include 550 rice growers randomly selected after stratification according to their marketing strategies,33 49 processing units, and 60 traders, randomly selected. We also used data from François et al. (2014), who carried out a survey of 254 traders in order to assess net margins along the downstream segment of the same VC in 2014. Retailers from Dakar and other major cities were randomly selected after stratification per quarter. They were surveyed on their costs and returns and asked to indicate their suppliers, who, in turn, were surveyed.

Institutional and technical changes in the rice value chain

Historically, public policies and global markets have either hindered or fostered modernisation of the rice VC (Fall, 2006; Bélières and Touré, 1999).

Hierarchy governance driven by the state (1964–87)

The expansion of irrigated rice growing started in the Senegal River Valley (SRV) at independence, in 1964 (Le Gal, 1995). State intervention supported the development of the VC: Each segment was directly or indirectly managed through two state agencies, SAED (Société Nationale d’Aménagement et d’Exploitation du Delta) and CPSP (Caisse de Péréquation et de Stabilisation des Prix). SAED set up the hydro-agricultural infrastructure at a rate of 600 ha per year from 1965 to 1980 (Bélières and Touré, 1999). SAED also provided producers with technical advice and subsidised inputs. The intensification of rice cropping started in 1973 (Le Gal, 1995), with land preparation, the use of high-yield and non-mixed varieties, mineral fertilisers, chemical weeding and mechanised harvesters. Farmers marketed their paddy to two rice mills managed by SAED, which bought it at a fixed price regardless of moisture and impurity content (Fall, 2006). CPSP was in charge of rice distribution. It highly taxed imports in order to subsidise the purchase of domestic paddy. This formal VC became deficit-ridden and collapsed (Fall, 2006) because the rice was sold at prices under processing and purchasing costs, and taxes on imports were not sufficient to cover the deficit.

In parallel to that formal VC, a traditional, informal one appeared (Bélières and Touré, 1999). Small-scale traders, called banabanas, used mills which only provided the function of husking and supplied unsorted rice with impurities (Fall, 2006). Producers used that VC to obtain a quick cash return, while it took several months with SAED. Some of them also used this VC to sell their produce without paying off their loans.

33 The database contains 265 producers involved in spot transactions, 155 producers involved in production contracts, and 130 producers involved in marketing contracts.

Since co-ordination between stakeholders was planned, the governance of the rice VC during this period was integrated, and the chain was driven by public bodies. The emerging informal VC had market governance with relational tendency.

Liberalisation and market governance (1987–2007)

State intervention reduced, national economy opened up to global markets

First, production factor markets were opened to competition in 1987 (land, credit, seed and pesticides). Land development was turned over to the private sector. Irrigated land increased from 23,000 ha to 40,000 ha in 1991 (Bélières and Touré, 1999). Investments were made in hydro-agricultural equipment of low quality in terms of drainage and solidity of bunds, resulting in low output. SAED continued its activity of production support. A national bank called Caisse Nationale de Crédit Agricole du Sénégal (CNCAS) was created (Fall, 2006). It proposed various loan formats for production, investment and marketing. In the case of production credit, the bank paid agri-suppliers who provided inputs to producer organisations, who repaid the bank once the paddy was sold. Credits grew from FCFA 150 million34 in 1987 to 5 billion in 1993 (Bélières and Touré, 1999) but the bank followed a financial recovery plan due to low reimbursement rates (Fall, 2006). CNCAS hardened its selection criteria. Other financial institutions got involved in the SRV, but they faced the same problem.

Development of the traditional value chain

Second, in 1994, the downstream part of the VC was privatised, prices deregulated and the currency (CFA35 franc) was devalued. Rice millers owned by SAED were privatised and the private sector was encouraged to invest through subsidies and development projects. Between 1981 and 1996, processing capacities increased by a factor of 13 and production increased by a factor of only 4.5 (Bélières and Touré, 1999). As a result, in 1996, the SRV had the capacity to process 164,000 tons of paddy but production reached only 75,000 tons. These figures include the development of small-scale processing units, which were paying paddy quickly and in cash (Bélières and Touré, 1999). Rice growing was funded by CNCAS. Only 2% of farms took out a loan from a banabana in 2005 (Fall, 2006).

From 1994 to 1995, the share of paddy processed by industrial units decreased from 62% to 11%, while small-scale units developed their activity (Bélières and Touré, 1999). From 1996 on, industrial units became unprofitable because of marketing subsidies being withdrawn, bad harvests, strong competition from small-scale units, high depreciation costs and a collapse in rice prices due to international competition (Bélières and Touré, 1999). This led to a concentration of the midstream segment. Some rice millers were able to continue obtaining supplies thanks to their relational proximity with producers and their ability to pay them quickly (Bélières and Touré, 1999). The governance changed from state hierarchy to spot transaction with a relational tendency. Local rice was of lower quality than imported rice because banabanas did not use moisture meters when purchasing their paddy, and they used simple husking techniques.

A favourable context supporting modernisation since 2007

It was recently demonstrated by experiments that local rice can compete with imported rice if its quality is adapted to the preferences of consumers, these preferences being aroma, homogeneity, purity of the grains, branding, and labelling (Demont and Ndour, 2015; Demont et al., 2013). Demont and Rizzotto (2012) proposed a three-stage policy sequence for modernizing the Senegalese rice VC. The first stage focuses on enhancing rice quality, though contracts, improvement of post-harvest practices and investments in modern techniques. The second stage is an increase in scale, through investments in storage infrastructure and increasing the working capital of the millers. The third stage is advertising to accelerate the transformation of consumer preference for domestic rice.

Table of contents :

CHAPTER 1: GENERAL INTRODUCTION

Context

Issues: An African modernization?

Theory: Institutional economics

Research questions and hypotheses

Case study: The domestic rice value chain in Senegal

Methods

Thesis outline

CHAPTER 2: THE ONGOING MODERNISATION OF THE RICE VALUE CHAIN IN SENEGAL: A MOVE TOWARD THE ASIAN QUIET REVOLUTION?

Introduction

Documented changes in food chain governance in Asia and Africa

Conceptual framework

Methodology

Institutional and technical changes in the rice value chain

Modernisation of the value chain

Increase in total net margin

Discussion: A Senegalese quiet revolution?

Conclusions and policy recommendations

TRANSITION 1: FROM THE GOVERNANCE OF THE CHAIN TO THE INCLUSION OF PRODUCERS

CHAPTER 3: PLURAL FORMS OF GOVERNANCE AND AGRICULTURAL FINANCING—THE CASE OF THE DOMESTIC RICE VALUE CHAIN IN SENEGAL

Introduction

Conceptual framework

Method and data

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

TRANSITION 2: IMPACT ESTIMATION STRATEGY

CHAPTER 4: THE IMPACTS OF CONTRACT FARMING IN DOMESTIC GRAIN CHAINS ON FARMER INCOMES AND FOOD SECURITY—EVIDENCE FROM SENEGAL

Introduction

Background

Methods and data

Results and discussion

Conclusion

CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSION

Aims of the study

Main findings

Policy recommendations

Limitations

Research agenda

APPENDICES

Chapters’ appendices

Posters

Chapter 6: Les effets des investissements d’agrobusiness sur les agriculteurs familiaux. Le cas de la vallée du Fleuve Sénégal

4. Guides d’entretiens et questionnaires

5. Résumé de la thèse