Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

CHAPTER 3 HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

This chapter develops hypotheses on cyclical variations in underreaction based on the links between analysts’ underreaction and economic incentives discussed in Chapter 2. The logic in developing the hypotheses is that if certain incentives vary with business cycles, then due to the incentive-underreaction links, analysts’ underreaction will accordingly vary with the business cycles. Thus, the hypotheses are dual tests for (1) analysts’ incentives vary cyclically and (2) underreaction is driven by analysts’ incentives. Specifically, section 3.1 focuses on the reputation-building incentive solely, hypothesising an association between business cycles and analysts’ underreaction in general.

The hypothesised association relies on the reputation effect literature and the asymmetric reputation cost theory, in particular. I start with predictions about cyclical variations in the factors that lead to underreaction, i.e., uncertainty and asymmetric reputation cost. Regarding the uncertainty hypothesis, I argue that during bad times, firms are reluctant and slower to disclose information, earnings are more likely to include large transitory items, and macroeconomic forecasts are of poorer quality. All these factors lead to greater uncertainty in recessions. Regarding the asymmetric reputation cost hypothesis, I draw on investor loss aversion theory and argue that expansionary periods are associated with greater investor loss aversion, and hence, a more severe reputation penalty when the signal implied by analysts’ forecasts is subsequently proven incorrect. This leads to greater asymmetric reputation cost during expansions. Finally, taking into account the predicted cyclical changes in uncertainty and asymmetric reputation cost (of which the directions are opposite), I hypothesise an unsigned relationship between business cycles and underreaction in general. Section 3.2 distinguishes good news and bad news when estimating underreaction to

earnings and earnings-related news. Based on the reputation theory, I predict that analysts will need to underreact more to good news than bad news in recessions, in order to protect themselves from reversing their forecast revisions, because good news is more likely to be reversed in bad times. I also consider the implications of short-term economic incentives as suggested in the prior literature. If short-term economic incentives are the main driving force, then one would expect that analysts will underreact more to bad news than good news in recessions when short-term economic incentives are stronger. Clearly, the conflicting incentives create a tension in predicting the direction of the cyclical variation in differential underreaction. As a result, I hypothesise an unsigned association between business cycles and analysts’ asymmetric underreaction to bad versus good news.

Underreaction in general

As previously noted, underreaction in general is related only to reputation-building incentives. The literature does not offer any theory on short-term economic incentives to explain underreaction in general. Thus, this section hypothesises the potential cyclical changes in underreaction in general, focusing on reputation-building incentives. Subsection 2.3.2 reviews a large body of research that demonstrates a positive reputation effect on analysts’ forecast quality. Reputation is associated with long-term economic benefits including job security, promotions, favourable job separations, and future broker trading volume (Mikhail et al., 1999; Hong et al., 2000; Hong and Kubik, 2003; Jackson, 2005). Hence, analysts are incentivised to improve the quality of their earnings forecasts due to the reputation effect. As the literature commonly uses forecast accuracy as a forecast performance indicator, the vast majority of existing studies on reputation-building incentives focus on accuracy. These studies provide evidence suggesting that reputable analysts produce more accurate forecasts than non-reputable analysts. Examples include Stickel (1992), Hong and Kubik (2003), Jackson (2005), Leone and Wu (2007), and Fang and Yasuda (2009). While accuracy is certainly important and a major contributor to forecast quality, it represents only one dimension of quality and the usefulness of earnings forecasts. A few studies investigate other dimensions of forecast quality. They document that reputation is positively associated with forecast frequency (Stickel, 1992), analyst conservatism (Hugon and Muslu, 2010), consistency in previous forecast errors (Hilary and Hsu, 2012), and larger market price impacts (in all the three studies).

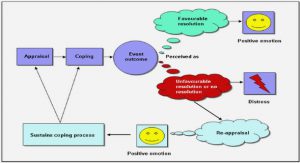

While some of these quality features might be correlated with each other, forecasts that contain different dimensions of quality obviously provide investors with different aspects of information. For example, Hilary and Hsu (2012) find that consistency in forecast errors has a positive effect on market price changes, and that this effect is even larger than that of accuracy when the proportion of institutional investors is higher. This implies that, for investors, other features of forecast quality are as important as, or more important than, accuracy. Therefore, I examine the link between reputation and a different dimension of analyst quality. Following reputation effect theory and Raedy et al.’s (2006) asymmetric reputation cost theory (see subsection 2.3.2 for detailed discussions), I focus on the consistency between analysts’ view about the firm’s future (e.g., the direction of forecast revisions) and subsequent news implications (e.g., earnings announcement). I argue that with the arrival of new information, analysts prefer not to fully incorporate it in forecasts, but underreact to new information while maintaining a certain range of accuracy. This way, they can create a higher probability of having the same direction between the signal implied in their forecasts and subsequent news, hence protecting them from incurring a larger amount of implicit reputation cost imposed by investors. Hugon and Muslu (2010) find evidence suggesting that the persistence between one- and two-year-ahead analysts’ revisions, an empirical example of consistency between analysts’ view and subsequent news, is demanded by the markets. The asymmetric reputation cost theory predicts that underreaction increases with uncertainty and asymmetric reputation cost. To gauge the impact of business cycles on underreaction, it is necessary to first evaluate how business cycles impact the two determining factors of underreaction. Hence, the following subsections hypothesise cyclical variations in uncertainty and asymmetric reputation cost, respectively.

Uncertainty and business cycles

The level of information uncertainty is likely to be different across business cycles due to several reasons. First, different states of the economy are associated with different disclosure behaviour, resulting in different levels of information richness. As discussed in subsection 2.4.1, prior research finds empirical evidence suggesting that earnings are procyclical (Chordia and Shivakumar, 2002) and that accounting losses are dominantly determined by recessions (Klein and Marquardt, 2006). Firms are more likely to have bad news in bad times. Brown (2001b) finds that managers in loss firms are reluctant to forewarn analysts of impending bad news. In a similar vein, Lang and Lundholm (1993) find that analyst ratings of corporate disclosures are lower for poor-performing companies than for well-performing companies. Hong et al. (2000) and Lim (2001) further confirm that when companies are sitting on bad news, managers tend to be less forthcoming. Therefore, firms are more reluctant and slower to disclose information at the aggregate level in recessionary periods, resulting in greater information uncertainty. Furthermore, firms show different reporting behaviour in different economic conditions. Prior research demonstrates that earnings are less persistent and earnings response coefficients are smaller in recessions (Johnson, 1999), and that earnings are more conservative in recessions (Jenkins et al., 2009). Analysts are faced with more uncertainty when firms may include more transitory items or recognise bad news faster in recessions. In short, the increased level of earnings losses, volatility, and conservatism are expected to increase the level of uncertainty about earnings during recessions. This expectation is consistent with evidence from prior studies, albeit indirectly, that loss firms and high earnings volatility firms are more difficult to forecast (Kross et al., 1990; Hwang et al., 1996). Moreover, the poor quality of macroeconomic forecasts for recessions creates greater uncertainty about earnings. The macroeconomic outlook is one of key inputs to analysts’ forecast models. The reliability of economic forecasts contributes to information certainty about firms’ future sales and earnings. However, the economic forecast literature has revealed that economists in US and world-wide generally are unable to predict recessions in advance, often underestimate the extent of recessions until late in the course of the recession, and are unable to distinguish between slow/negative growth and rapid growth (see Higgins 2002a for more details). Reasons include the lack of reliable real-time data and predictive models, and the lack of incentives for forecasting recessions. This predictive failure in recessions makes forecasting earnings more difficult. This is consistent with Chopra’s (1998) and Higgins’ (2002a) findings of more inaccurate earnings growth forecasts and earnings forecast during recessions. During recessionary periods, economic indicators have started to show unfavourable signs. Given the poor quality of the macroeconomic forecasts for recessions in history, financial analysts are more uncertain about economic growth rates, which they use to project sales and earnings, than in an expansion. Thus, uncertainty about future sales and earnings is expected to be greater in recessions than in expansions. The above three arguments unanimously suggest uncertainty to be greater in recessions than expansions. Consistent with this expectation, Higgins’ (2002a) finds that forecast dispersion (a well-used proxy for information uncertainty) is greater in one recessionary period than other non-recessionary periods. Accordingly, my first hypothesis is (all hypotheses are stated in the alternative form): H1a: Uncertainty about future earnings is greater during recessions than during expansions. The asymmetric reputation cost theory posits that analysts’ underreaction increases with uncertainty and asymmetric reputation cost. While asymmetric reputation cost is a relatively new concept in the literature, the effect of uncertainty on analyst underreaction has been examined empirically. Zhang (2006) presents evidence that greater information uncertainty predicts greater analyst underreaction, i.e., more positive (negative) forecast errors and subsequent forecast revisions following good (bad) news. Raedy et al. (2006) find underreaction increases with uncertainty measured by the length of forecast horizon. Clement et al. (2011) view analyst underreaction as a cautious reaction to uncertainty or ambiguity in the precision of a signal: “to the extent that analysts are uncertain about how informative a stock return or analyst revision is likely to be, we expect them to temper their use of these signals, consistent with psychological research on conservatism and ambiguity aversion” (p. 282). While they take a psychological perspective to explain underreaction, their view nonetheless supports the positive effect of uncertainty on underreaction. Given the existing theory and empirical evidence on the uncertainty-underreaction link, a reasonable prediction as an extension of H1a would be that analyst underreaction is greater in recessions than expansions ceteris paribus. Next, I study the other factor that leads to underreaction, i.e., asymmetric reputation cost.

Asymmetric reputation cost and business cycles

As discussed in subsection 2.3.2, investors have the power to impose implicit reputation costs on analysts via investment decisions and responses to surveys ranking the analysts. This is demonstrated by empirical links among forecast quality, analysts’ rankings, and market response. Prior studies find that investors’ value function determines their investment decisions and, consequently, influences their investment performance. Clearly, investors’ decisions in evaluating analysts hinge on investors’ own value function, as much as analysts’ forecast quality. In the following paragraphs, I briefly discuss loss aversion (a widely accepted value function theory in the economics and finance literature) and its linkage to asymmetric reputation cost theory. Drawing on Hwang and Satchell (2010) who find that loss aversion changes depending on market conditions, I develop a hypothesis on the association between asymmetric reputation cost and business cycles.

Kahneman and Tversky’s (1979; 1992) prospect theory is widely accepted in the literature to describe investors’ value function. According to prospect theory, individuals are concerned with the changes in wealth (in terms of gains or losses) rather than with its final state. Moreover, individuals are more sensitive to losses than to gains – an individual feels more painful with a loss than he feels happy with an equal-sized gain. Specifically, an individual’s value function is concave with respect to gains and convex with respect to losses, and the value function has a much steeper slope for losses than gains. This phenomenon is referred to “loss aversion”.

Empirical research has examined prospect theory in the equity markets. Evidence has accumulated that investors (including professional investment managers) have an asymmetric risk attitude towards gains and losses when making investment decisions and that they are more concerned with losses than gains, confirming loss aversion theory. Examples include Shefrin and Statman (1985), Olsen (1997), and Ding et al. (2004) among others. Abdellaoui et al. (2007) further find the existence of loss aversion both at the aggregate and at the individual level. Investors’ loss aversion has implications for asymmetric reputation cost. Loss aversion and asymmetric reputation cost are linked due to the fact that investors use analysts’ forecasts to make investment decisions. Numerous studies have documented that forecasts have information content (see Ramath et al., 2008a, for details). A recent example, Beaver, Cornell, Landsman, and Stubben (2008), find forecast errors, and quarter- and year-ahead earnings forecast revisions have significant effects on stock prices, indicating that each conveys information content. In particular, quarter-ahead forecast revisions are relatively more important in affecting stock prices. This, among many others, provides evidence that investors do act on analysts’ forecasts. I have discussed in subsection 2.3.2 that investors who buy or sell stocks based on forecast revisions stand to lose when later news contradicts analysts’ opinion about the firm’s prospect (e.g., forecast revisions), and this is a major reason why asymmetric reputation cost arises. When investors are more afraid to incur a loss, they would experience a greater amount of displeasure for the same amount of loss.

Consequently, investors would impose higher implicit reputation costs on the analyst (e.g., via ranking systems) if subsequent information creates a reversal of expectations about the firm. To this effect, one can reasonably expect that greater investors’ loss aversion leads to greater asymmetric reputation cost imposed on analysts. Hwang and Satchell (2010) find evidence suggesting greater loss aversion in good times than bad times. They examine the robustness and appropriateness of loss aversion utility functions in financial markets. Specifically, they use a typical asset allocation problem for investors with loss aversion utility to determine the appropriate ranges of loss aversion parameters, including two curvature parameters explaining the sensitivity of utility to losses and gains, and a coefficient of loss aversion measuring the relative disutility of losses against gains. They find that US investors are more loss averse than Kahneman and Tversky (1992) suggest and because the curvature on losses is larger than that of gains, investors are more sensitive to the changes in losses than to the equivalent changes in gains. Importantly, in their analytical part, they find that the loss aversion coefficient is larger during boom periods (or bull markets) than during recessions (bear markets), indicating that loss aversion changes depending on market conditions. Their empirical results, based on US and UK data, support their analytical results. In particular, they propose a loss aversion coefficient of 3.25 for the US investors, which should be increased and reduced by 1.5 during bull and bear markets, respectively. These calculated numbers demonstrate the significance of the effect of market conditions on loss aversion.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

LIST OF TABLES

LIST OF FIGURES

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Research objective

1.2 The link between reputation and underreaction

1.3 Specific research questions

1.4 Summary of findings

1.5 Contributions

1.6 Thesis structure

CHAPTER 2 BACKGROUND AND RELATED STUDIES

2.1 The role of financial analysts and earnings forecasts in capital markets

2.2 Inefficiency in earnings forecasts

2.3 Analysts’ incentives

2.5 Summary

Appendix 2-A

CHAPTER 3 HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

3.1 Underreaction in general

3.2 Asymmetric underreaction to bad news versus good news

Appendix 3-A

CHAPTER 4 RESEARCH DESIGN

4.1 Forecast timeline

4.2 Variable Measurement

4.3 Models

CHAPTER 5 DATA AND RESULTS

5.1 Overview of analysts and forecasting activities across business cycles

5.2 Sample Data

5.3 Regression results

5.4 Robustness tests

5.5 Summary

CHAPTER 6 FURTHER STUDY

6.1 Earnings cyclicality

6.2 Earnings quality

6.3 Analyst following

6.4 Summary

CHAPTER 7 CONCLUSION

REFERENCES

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT

FINANCIAL ANALYSTS’ UNDERREACTION AND REPUTATION-BUILDING INCENTIVES